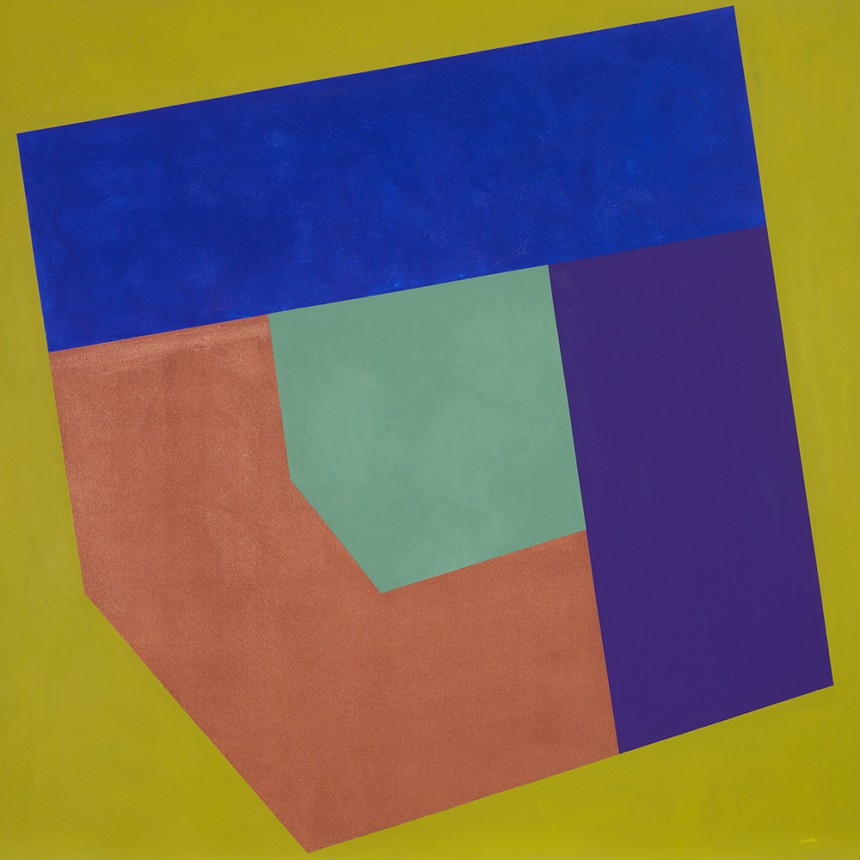

Abstract painting is alive and well, and Ric Evans is in top form. His new paintings are youthfully bold – or is it old-masterly confident? – tightly bound geometric compositions with quirky colours, contrasting paint surfaces and unstable locations. These are the larger rectangular paintings. Then there are the smaller diptychs and triptychs, whose external shapes are more idiosyncratic. At first sight it takes more than a moment to realize that the panels in each set are indeed identical. Their unpredictable internal subdivisions and their eccentric colours cast even that certainty in continual doubt. Instability is the constant state of Ric’s paintings. They are compositionally whole, but the eye can’t hold them still. Encounter, with its mustard-coloured ground against which three sturdy rectilinear planes churn around a center core like the arms of some big industrial mixing machine. An angular, glistening, copper shape in the bottom left pushes up at a luminous cobalt blue rectangle above, which in turn must weigh down on a dark purple, irregular rhomboid on the right, which then shoves along the original copper shape. So it goes, round and round – working both clockwise and counter-clockwise – in a concatenation of muscular actions that fire up our own internal mirror neurons, inundating our bodies with emphatic emotional responses.

Ric Evans, Encounter, 2016, acrylic on canvas on board, 68″ x 68″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Ric Evans, Encounter, 2016, acrylic on canvas on board, 68″ x 68″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

If geometry implies measure and system, while colour stokes the sensual and the intuitive, what is Ric’s system? A decade or so ago his rules were more upfront, but in this exhibition, his workings are freer, more instinctual and improvised. Ric is a consummate colourist, he declares his colours individually, each independently holding its own. When he juxtaposes them, adjacent colours learn provisionally to co-exist, but not without border tensions. As important to these paintings is their material body. Paint is variously applied, smooth or brushed onto solid supports, the larger canvases stretched over wood panels. To make the smaller diptychs and triptychs, Ric has applied his paint with a palette knife in some cases, directly onto birch panels.

Ric Evans, Changing Location, 2016, set of 3, oil on panel, 21″ x 19″ each. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Ric Evans, Changing Location, 2016, set of 3, oil on panel, 21″ x 19″ each. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Ric’s work emerged in the mid-1970s, when painting faced two important challenges, one from outside the discipline and another from inside it. This was when the serious art world was turning hostile to painting altogether, and when its future was not altogether certain. Painting had come to pose a number of problems. From a post-modern perspective, modernist painting’s claims to timelessness and universality were bankrupt because, as we now learned, all artistic utterances were merely contingent outcomes of specific temporal social and political conditions. Geometric abstraction was doubly suspect because its underlying geometric structures were concomitantly revealed – whatever a Mondrian or a Newman may have believed – to signify neither utopian nor transcendental values, but were rather abstract codifications of oppressive political or bureaucratic systems of power. In any case, with the availability of a range of new technologies, painting’s craft-based practice had apparently outlived its usefulness.

Ric Evans, Still Form, 2016, acrylic on canvas on board, 40″ x 30″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Ric Evans, Still Form, 2016, acrylic on canvas on board, 40″ x 30″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Painting, of course, survived and proved to be indispensable to art’s toolbox, but not without a changed sense of itself. Ric also came into his own in a climate of Minimalist art in which painting sought to forefront its status as a material object. This was in the mid-1960s and into the 1970s, when stretchers thickened and frames disappeared. Eugene Goosens, in his text for the MoMA exhibition, The Art of the Real in 1967, described how each work in the show was literally ‘real’ because it offered “itself for whatever its uniqueness is worth in the form of a simple irrefutable object.” In this situation one found oneself physically on equal footing with the painting, co-existing with it in a shared space, another independent piece of reality with a certain height, width, depth, colour and texture.

Ric Evans, The Flow of Surprise (Double Green, Magenta and Yellow), 2016, set of 3, oil on panel, 37 1/2″ x 23″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Ric Evans, The Flow of Surprise (Double Green, Magenta and Yellow), 2016, set of 3, oil on panel, 37 1/2″ x 23″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Thus when Ric made his museum debut in 1975 in an Art Gallery of Ontario group show simply entitled Four Painters, and was asked by the curator to describe his work for the catalogue, he simply gave the facts: “Ric Evans paints 6 in. vertical bands of artist’s oil colour on a ground of latex interior house paints, on canvases 3 ft. by 6 ft.” Along with his colleagues in the exhibition, he defined the “most obviously common aspects” of their work as “reduced means, serial format, denial of illusion and illustration.”

The particularity of Ric’s paintings has been how he constructs, using coloured and textured shapes, a succession of relationships that are always in tension. We can seize them only piecemeal, and then strive to put them wholly together. The experience of painting has never been a passive one, as its distractors have claimed, but Ric’s painting thrives on immersing its viewers in experiences of change, dislocation and decenteredness. Their world remains in flux, imagined orders emerging, dissolving and remerging.

Ric Evans, Appearances of Certainty, 2016, acrylic and oil on canvas on board, 60″ x 60″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Ric Evans, Appearances of Certainty, 2016, acrylic and oil on canvas on board, 60″ x 60″. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

If there is existential meaningfulness to staging perceptual performances of mutating instability as if they were surrogates for the vagaries of everyday human experience, in Ric’s work it presupposes neither despair nor melancholy. It is on the contrary both exciting and celebratory. As I have said before, in Abstract Painting in Canada: “Up-front, quirkily so, as Evans’ compositional structures often are, it is nevertheless when he pits structure against destabilizing contraries that his more recent painting delivers its aesthetic pizzazz.”

Roald Nasgaard

*Note: The article was originally written for Nicholas Metivier Gallery and published on its website. We thank the gallery for their permission of posting it in artoronto.ca.

**Exhibition information: September 8 – 24, 2016, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, 451 King Street West, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat, 10 am – 6 pm.