“Cultural identity […] is a matter of ‘becoming’ as well as of ‘being’. It belongs to the future as much as to the past” – Stuart Hall, “Cultural Identity and Cinematic Representation.”

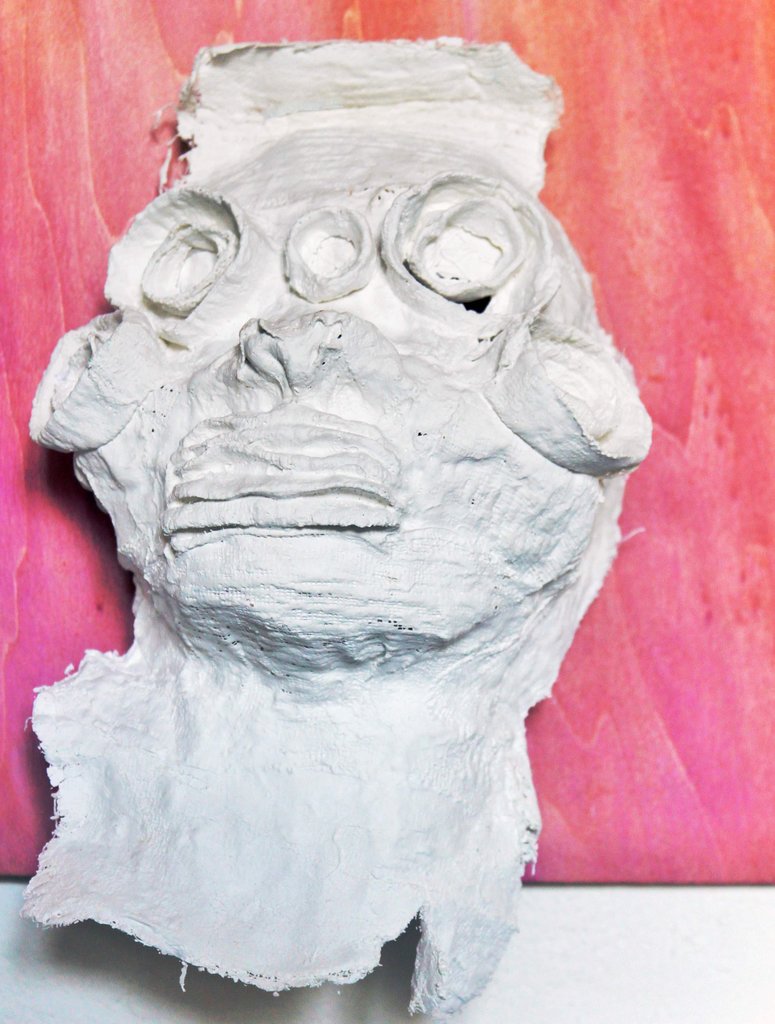

Aisha Z. Simpson, Cipher, Paper Machè, Watercolor, Acrylic, Tape, Mosiacs, Stones, Beads, 11 x 11 inches. Coutesy of the artist.

Aisha Z. Simpson, Cipher, Paper Machè, Watercolor, Acrylic, Tape, Mosiacs, Stones, Beads, 11 x 11 inches. Coutesy of the artist.

It isn’t difficult to see why Aisha Simpson would feel drawn to work with masks during her residency in Florence in 2012. The city percolates in its own history, with masks become the literal face of the population, embodying a shared experience and the interface of present and past. Masks stand in for ideas, figures, and archetypes; they relay historical knowledge to the present and unite current mores with the shared experience of the past, forming a powerful locus for the articulation of a population’s sense of self.

Aisha Z. Simpson, Inception, Paper Machè, Watercolor, Acrylic, Tape, Mosiacs, Stones, Beads, Ceramics, 6 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Aisha Z. Simpson, Inception, Paper Machè, Watercolor, Acrylic, Tape, Mosiacs, Stones, Beads, Ceramics, 6 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Masks have figured prominently in art history, too, informing the avant garde of what came to be Modernism as it is usually ascribed, and underlying acts which we celebrate and decry today as appropriation. However, the material and psychic space between the seizure and appropriation of primarily African masks by European Modernists and the organic and continuous generation of new masks and new meanings in Florence is pointed and poignant. As Stuart Hall astutely observes, “everything which is historical… undergo[es] constant transformation,” but European Modernism’s appropriation of African masks transfixed them in history as objects of the ‘primitive’ past only, and not as living emblems of culture.

Aisha Z. Simpson, Bambara Inland, West Africa, Paper Machè, Watercolor, Acrylic, 6 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Aisha Z. Simpson, Bambara Inland, West Africa, Paper Machè, Watercolor, Acrylic, 6 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

With her series Fictions and Figments, Simpson produced masks that posit a continuous history, masks that aren’t treated as relics or artifacts, but as authentically imagined expressions of ongoing cultural contingency. Drawing from examples from various pre-colonial peoples and locales of Africa, her masks are not contemporized or updated so much as extrapolated, implying hypothetical histories where the politics and cultures of the African continent were not crudely written by bloodthirsty Western imperialism, but flourished in egalitarian exchange. The masks enact a kind of Afrofuturism in the vein of theorist Kodwo Eshun, which aims to reorient the “intercultural vectors of Black Atlantic temporality towards the proleptic as much as the retrospective.” (Kodwo Eshun, “Further Considerations of Afrofuturism.”)

Aisha Z. Simpson, Lagoon Regions Coast ofWest Africa, Paper Machè, Watercolor, Acrylic, 6 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Aisha Z. Simpson, Lagoon Regions Coast ofWest Africa, Paper Machè, Watercolor, Acrylic, 6 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

The invocation of Paul Gilroy’s notion of the Black Atlantic is especially appropriate given the materials employed in the masks’ creation. Using Florentine ceramics, Venetian beads, mosaics from Ravena and working out of a local mask workshop, Simpson’s practice hinges neither on appropriation or conservation, but becomes the site of genuine transnational exchange. She develops a hybridity that rests on the value of both parts, and not the imposition of one by the other.

Mark Dery begins his tremendous essay “Black to the Future” with a provocative question: “Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, imagine possible futures?” (Mark Dery,“Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose.”)

Aisha Z. Simpson, Zero, Paper Machè, 11 x 11 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Aisha Z. Simpson, Zero, Paper Machè, 11 x 11 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Though Simpson’s masks remember a history that didn’t transpire and imply a future that won’t actually exist, they suggest alternate stories and speak to the futures that might have been—and might still be—possible.

Ben Bruneau