Surveying the work on display at Daniel Faria Gallery brought to mind a prescriptive remark by artist Joseph Beuys, that ‘things start to go wrong when someone sets about buying stretchers and canvasses’. Yes, one of the works is indeed on canvas – we’ll return to that presently – but what stands out for me is that the participating artists in this show have moved far beyond any fine art tradition. We might think of modernism as the rebelling against that tradition, but here the tradition is dead, buried and forgotten. I have not belatedly discovered postmodernism. That movement, at least in apocryphal terms, was shaped by a rebelling in turn against modernism.

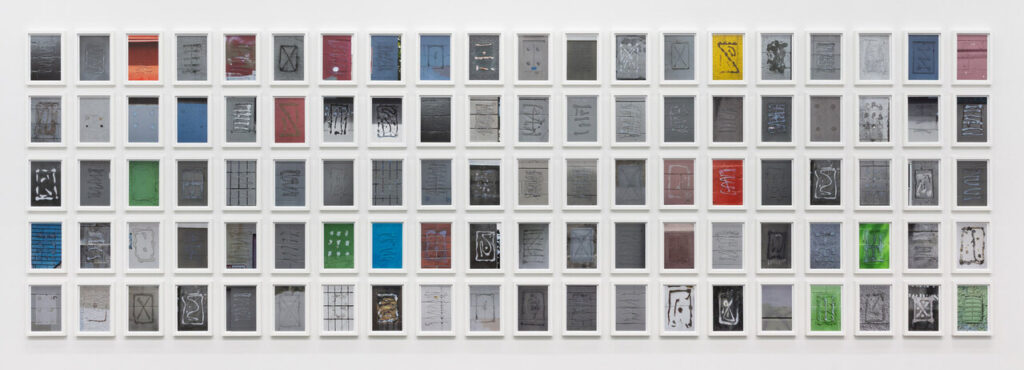

Installation view, Traces at Daniel Faria Gallery, 2026. Photo: LF Documentation.

There is no narrative, i.e., text, for which any author can be denied, to paraphrase postmodernist theory. No meaning can be gleaned directly from the works scattered around the space. The viewer’s predicament is analogous to someone watching a theatre show in which there is no discernible plot or story. Instead the actors on the stage gesture thus and so, engaging in brief banal conversations, until the play ends – like an art performance perhaps. All, nonetheless, is clearly choreographed meticulously.

Consider the show’s centrepiece by Andrew Dadson, namely, a beautiful grid of one hundred framed photographs of residual glue found on various walls after some street sign has been pulled off. These marks, it is pointed out, are ‘surprisingly calligraphic and painterly’. It is hard to think of something more mundane than this as subject matter. Of course, what the artist is intimating is how these residual marks are strikingly reminiscent of pictograms and ancient writing, e.g., cuneiforms. Still, the work is bereft of any substantive content, so the casual viewer is left wondering why the artist has chosen to make it. The same can be said of most of the works here.

Andrew Dadson, Cuneiform (#305-404), 2015-2022, 100 inkjet prints, 12 x 8¾ inches each.

One exception, perhaps, is Oluseye’s wall-mounted scuptures titled Ploughing Liberty. Here the title is a clue as to what the work is about. Oluseye is an ethnic Nigerian born in the UK. He has researched the history of black loyalists and fugitive slaves in Nova Scotia, who ended up labouring on the land. What we see is a set of antique farming implements with hockey sticks attached at the bottom. These worn tools are a testament to that life of toil, while the hockey sticks are emblematic of the culture of leisure that these labourers have always been excluded from. These artefacts stand on their own as beautiful objects which, by artful lighting, cast shadows on the white wall to dramatic effect.

Oluseye, Ploughing Liberty, 2024-2026, Antique farm implements, found hockey sticks and brass dowels.

Shadows play a very different role in the pedestal mounted sculpture by Jennifer Rose Sciarrino, titled North Facing, December 21. Here we leave the physical world. Sciarrino first created a virtual, i.e., computer generated ‘sculpture’. Then she set about working out the shape of the shadow this virtual sculpture would cast on the ground on the day of the winter solstice. Once recorded this shape was cut in real stone, which is what we see on the pedestal. We have an imagined shadow traced by an imaginary sculpture, made concrete.

Jennifer Rose Sciarrino, North Facing on December 21st VI, 2014, Concrete, 3 x 9 x 12 inches.

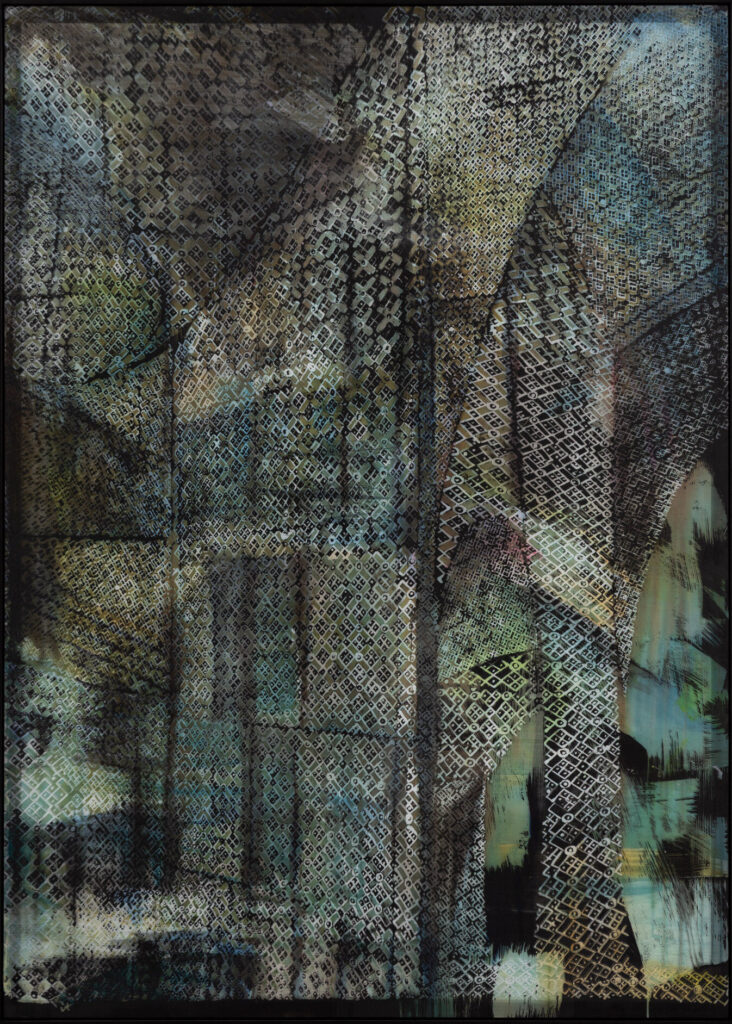

This flight from the physical world to a virtual one is echoed in the work of Shannon Bool. Bool has taken images of buildings found on the internet. These images are somehow incorporated into a batik-printed pattern made on silk fabric. Finally the fabric is stretched over a mirror, so that both it and the viewer are reflected back in the work. Bool’s achievement, we are told, is to ‘take the static modernist grid and open it up to the environment, making it unfixed and negotiable’. This is art gone relexive, that is, work which is centred on its own making and reception.

Shannon Bool, Veiled Facade, 2026, Oil, fabric paint and batik dye on silk, plexiglas mirror, 65 x 46¾ inches.

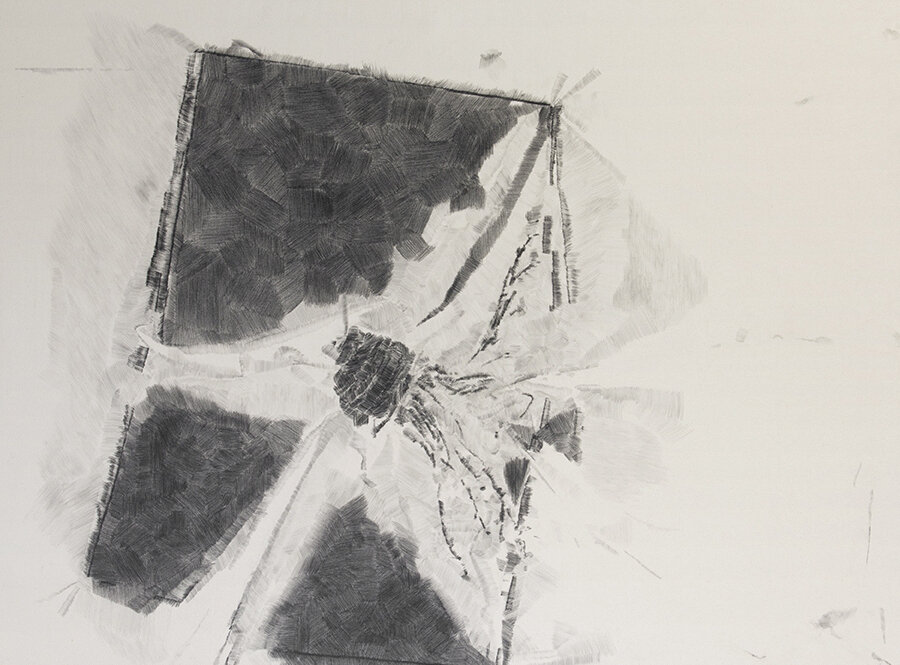

This reflexivity is also evident in Derek Liddington’s work, given the following convoluted title: The plant proceeded to tip as I drew it, at which point I made a decision to let it fall as I felt it would improve the composition. Liddington placed the canvas over a plant on a table and attempted to draw on it his interpretation of what lay underneath. That is when the plant tipped over etc. How does this work engage the viewer? I can only speak for myself – there was little I could relate to. It is clever and humorous, in its title at least.

Derek Liddington, The plant proceeded to tip as I drew it, at which point I made the decision to let it fall as I felt it would improve the composition., 2015, Graphite on canvas, frame: watercolour on maple, 61 x 81 inches.

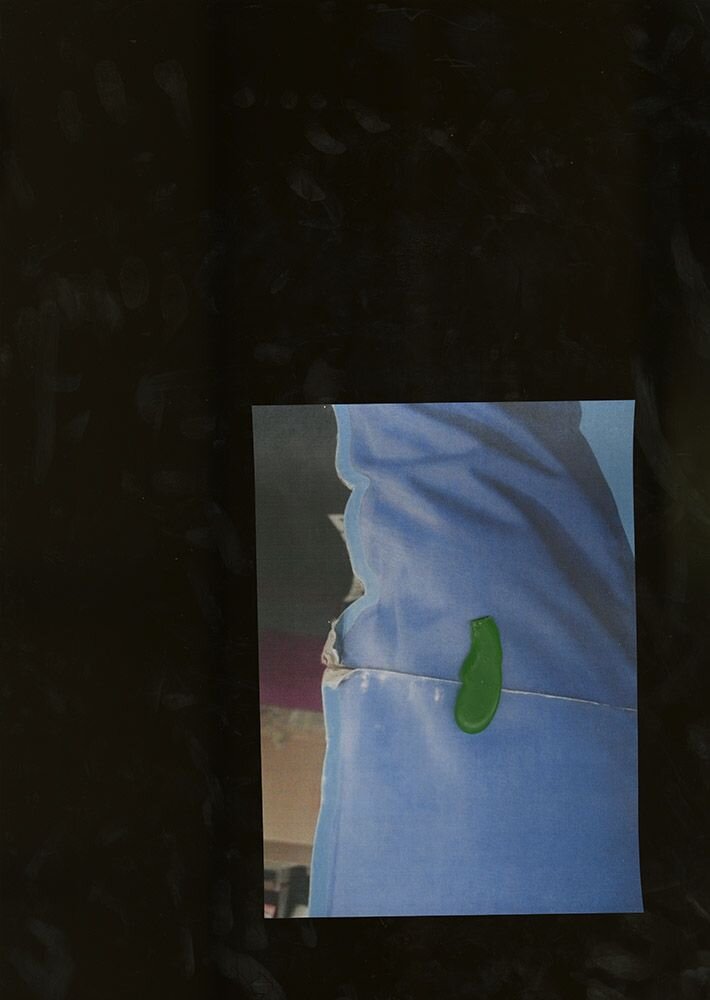

Nadia Belerique – a master of installation art – is represented by a series of photographic prints titled The Archer. These feature experiments using a home-office scanner. Everyday objects are scanned while manipulating the light, and the images include smudges on the glass made by Belerique’s hand in the process. Once again we see art that focusses on its own making, where little is communicated otherwise.

Nadia Belerique, The Archer 6, 2014, Inkjet photograph mounted to aluminum and plexiglas, 28 x 20 inches.

Traditionally, art played a role in creating stories and narratives to make sense of, and reflect on, our world. This role has since been largely fulfilled by film, television, as well as written media. Concurrently art has increasingly turned away from the world as we experience it. What is left for the artist to communicate is unclear. In this show we see some of the countless attempts, nevertheless, by fertile minds – those who are essentially compelled to exercise their creativity and talents – to engage the viewer. These efforts, we can see, often lead to beautifully composed ‘hymns’ to art itself. Art about the making and viewing of art. Is that a worthy enterprise? I don’t know. All the same, these works display a cleverness, and are clearly designed to impress the viewer in some way or other.

Installation view, Traces at Daniel Faria Gallery, 2026. Photo: LF Documentation.

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of Daniel Faria Gallery.

*Exhibition information: Traces / Group Show, January 17 – February 21, 2026, Daniel Faria Gallery, 188 St Helens Ave, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Fri 11 am – 6 pm, Sat 10 am – 6 pm.