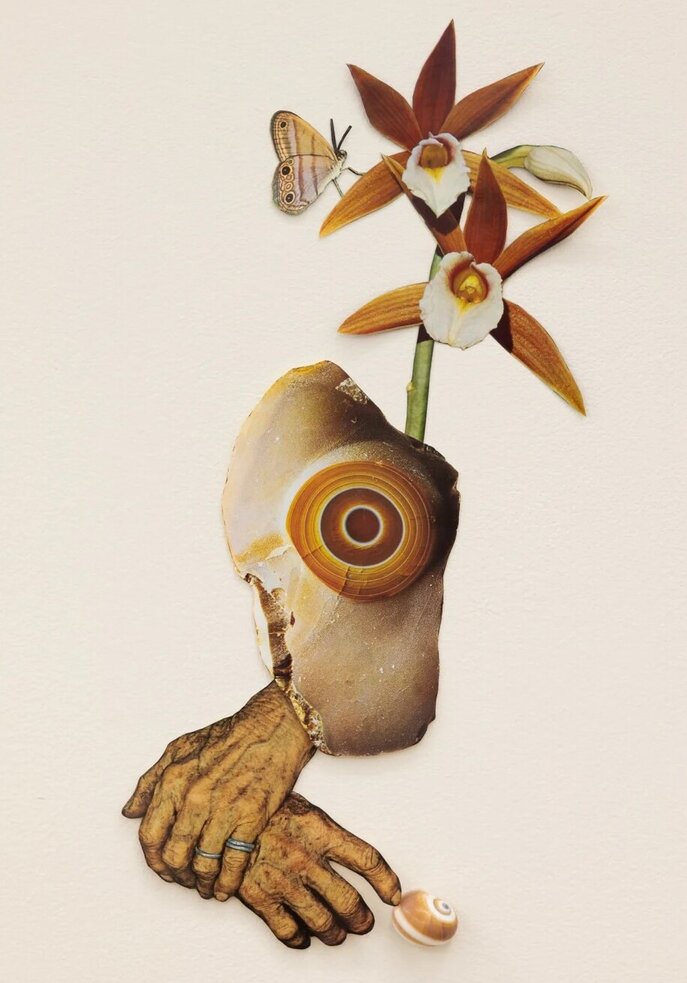

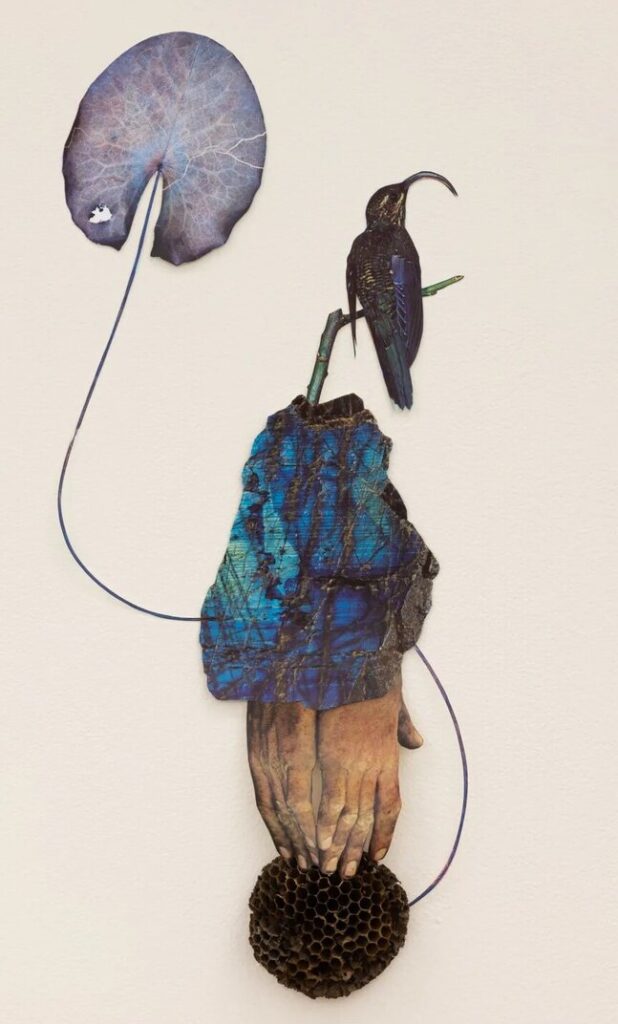

This is the second opportunity I have had to review Murphy’s work, again at Clint Roenisch Gallery. As I remarked previously, her work sits on the margins of contemporary art practice, insofar as we can speak of the mainstream in art any more. She collects printed images from natural history books and magazines, and also small items from nature – shells, fossils, seed pods, feathers and so on. Using these she assembles delicate minimal collages. Each assembly is a poem about the natural world and our relationship to it. They reflect her abiding fascination with ecology and natural history. It is difficult to decide if she is a natural historian making art or an artist doing natural history. Of course, the two might not be mutually exclusive – it could be a false dichotomy.

Installation view of Jennifer Murphy, Grains of Sand at Clint Roenisch Gallery

Her poems, as I have chosen to call them, are in essence constructed from readymades. And it is no accident, I feel, that her practice in this sense parallels those of some of the Dada movement in the early twentieth century. Dadaist Tristan Tzara, for example, explained how to make a Dada poem: First find a newspaper article, cut out all the words individually, place them in a bag, shake them up and pick out the words one after the other – the order they randomly come out produces the desired poem. Likewise Murphy cuts up images from chosen books and magazines. Although how she combines them, unlike the Dadaist, is not determined by chance.

Jennifer Murphy, Renunciation of the Self for Future Generations, 2025, used book paper collage, shell, 16 x 28 inches

Dada arose in reaction to the seismic political and economic upheavals of the time, while the First Great War was underway. Events reached an absurdity of tragic proportions. Politics became a cruel spectacle full of hate and wanton destruction, driven by the greed of the ruling class – pleonexia, as I have heard one commentator, named Richard J. Murphy (coincidentally), aptly call this phenomenon. Ditto today. She is motivated, as she explains, by ‘our current world full of converging emergencies including the rise of fascism, disinformation, war and forced displacement, grave inequality, resource depletion, and the climate disaster, which are all exacerbated by colonial, capitalistic, and extractive forces.’ A veritable litany of woes.

Jennifer Murphy, Woven Together, 2025, used book paper collage, shell, 16 x 24 inches

The tone of Murphy’s work is very different from that of the Dadaists, whose brash performances and blatant absurdity reflected that of society at large. Murphy’s is more a lament – a hushed tone that is easier to pass over. She points to the fact that we are bounded by nature and the chaotic forces that drive it. In nature there is a procession of extinctions, as life-forms spring up and disappear with an inevitability that parallels our own births and deaths. Accordingly, she talks of interdependencies in between ourselves and the rest of nature, and declares that through her work she hopes “to highlight our role and responsibility to the world’s fragile ecosystems and one another by harnessing an attentiveness through beauty, levity and wonder”.

Jennifer Murphy, To Hold Dust, 2025, used book paper collage, coal, 15 x 22 inches

The qualities of ‘beauty, levity and wonder’, that Murphy strives for, contrast with the Dadaists’ expressions of anger and dismay. For them events pointed to the absurdity or meaningless of life, hence their celebration of nonsense poetry for example. The civilization we have constructed, by so-called rational means, is in fact ‘logically nonsensical’, to paraphrase Hans Arp. Murphy’s reaction to our current crises couldn’t be more different. Her work shares none of the didacticism of the Dadaism, its overt politics. Rather, she aims for pathos – a sense of wonder and tenderness. She appears to see in nature a path to redemption, based on a secular version of the thought expressed by Samuel Coleridge when he wrote, that on observing nature, ‘shalt thou see and hear the lovely shapes and sounds intelligible of that eternal language, which thy God utters, …’ (Frost at Midnight). According to Murphy: “To navigate and survive our world today and to grasp these complex interconnections inherent to it we must embrace solidarity, empathy, wonder, and a radical persistent resilience to imagine a more caring, collective future”. These are qualities she wishes to encourage us to value.

Jennifer Murphy, Faith in Life, 2025, used book paper collage, honeycomb, 16 x 28 inches

Collage and ready-mades are media that lend themselves to conceptualism, be it in the intellectual form of Marcel Duchamp or the political messaging of Hannah Höch, for example. In particular, they suited Duchamp’s rejection of the retinal, i.e., the aesthetic qualities of art. But clearly Murphy’s collages are meant to be beautiful. Her visual haikus are so ‘retinal’, in fact, they crowd out any concepts underlying them. As artefacts in themselves – imagine their being excavated centuries into the future, say – they are not readily relatable to the political and ecological crises she lists. But that is fine since they nevertheless succeed in expressing the wonder and beauty of the natural world, and ourselves as part of it. In this sense, her demonstrable passion for, and commitment to, nature is infectious.

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of Clint Roenisch Gallery.

*Exhibition information: Jennifer Murphy, Grains of Sand, December 13, 2025 – January 31, 2026, Clint Roenisch Gallery, 190 St Helens Ave, Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed – Sat 12 – 5pm.