In a modest sized gallery on Richmond Street West, curator and artist Leah Oates has presented an exhibition of small works titled Chaos Theory. The show only lasted a week – a pop-up one might say – and featured the works of nineteen artists. The artists are Marcy Brafman, Jack Cunningham, Yevgeniy Fiks, Greg Hendren, Max Kershaw, Miles Ladin, Yuliya Lanina, Sascha Mallon, Daniel Maluka, Joseph Muscat, Frances Patella, Jayden Pithwa, Dominique Prevost, Doris Purchase, Steve Rockwell, Greg Sholette, Chahat Soneja, Max St-Jacques and Pierre St-Jacques. The show falls under Station Independent Projects that was founded by Oates years ago, in New York City originally. She has extended the project to Toronto where she now lives.

Installation view of Chaos Theory at Remote Gallery. Courtesy of Station Independent Projects

Oates tirelessly promotes artists that she describes as emerging and mid-career, in other words a full range of artists, none of whom are represented by a commercial gallery. The theme of this show, chaos, gradually came to her. Everyday experiences taught her that chaos is an essential element of society. What does she mean by chaos or chaos theory exactly? Here it is a concept synonymous with disorder, lawlessness and randomness. Indeed, for a system to be said to be chaotic it must be unpredictable. In mathematics and physics – from which the term chaos theory derives of course, – the overall unpredictability of a system somehow emerges from its constituent elements that are ruled by seemingly strict laws. Likewise, Oates observes, while order in society generally prevails, there are unpredictable actors who threaten, and sometimes do, shake things up.

Miles Ladin, Cherry Bomb, 2016, digital pigment print 19 x 13 inches. Courtesy of Station Independent Projects

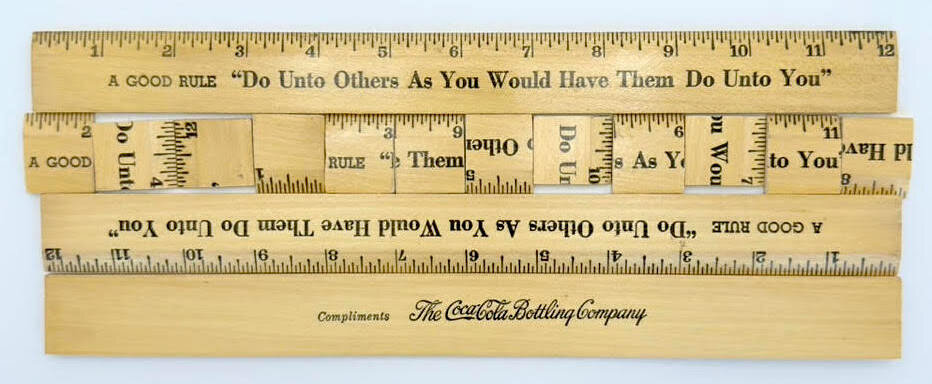

So the artists in this show have reflected on this notion of chaos, and included it in their works. For example, Hendren made his wall sculpture specifically for this show. Titled How Do We Measure Now? highlights the lack of control we feel when things are in disorder. We lose our perspective, end up at sea. This is particularly felt in moral terms, as suggested by Hendren’s quote of the golden rule: ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’. And in Pithwa’s self-portrait his features are almost indiscernible. We see, rather, a swirl of movement. Here one is reminded of the origin, or etymology, of the word chaos, namely, as a cosmological term referring to primordial matter that was formless.

Greg Hendren, How Do We Measure Now?. Courtesy of Station Independent Projects

Jayden Pithwa, Self portrait. Photo: Hugh Alcock

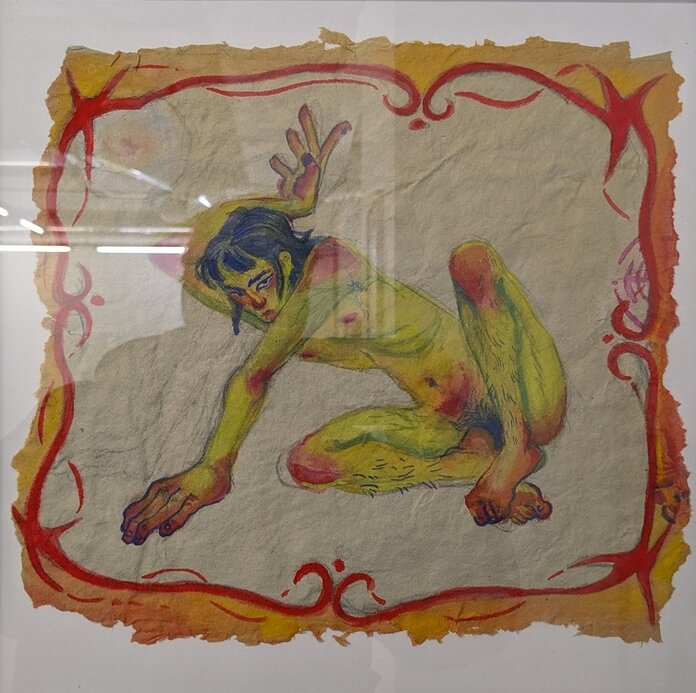

Indeed, the ancient Greeks believed that chaos is demonic, sinister in nature. Disorder implies uncertainty and mischief, or malice even. We see this quality, for instance, in Kershaw’s impish figure or in some other portraits. When things become unpredictable, volatile – climate change being a prime example of this, with the increasing unpredictability of weather events such as floods, hurricanes and droughts, – we become more vulnerable to the harms that result. Events threaten to be monstrous. Oates acknowledges the negative impacts of chaos, but she also sees it as an opportunity. The shaking up of things opens up the possibility of positive change.

Max Kershaw, Self portrait. Photo: Hugh Alcock

Portrait by Pierre St-Jacques. Courtesy of Station Independent Projects

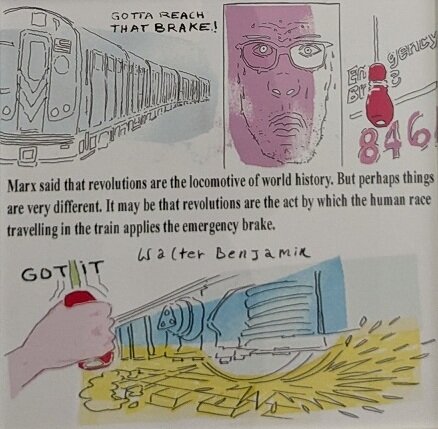

In the political sphere implied here we call this revolution of course. This point is literally spelled out in one of Sholette’s drawings where it states: ‘It may be that revolutions are acts by which the human race travelling on the train applies the emergency brake’, quoting Walter Benjamin, who lived through, and died in, the chaos of the second world war.

Drawing by Greg Sholette. Photo: Hugh Alcock

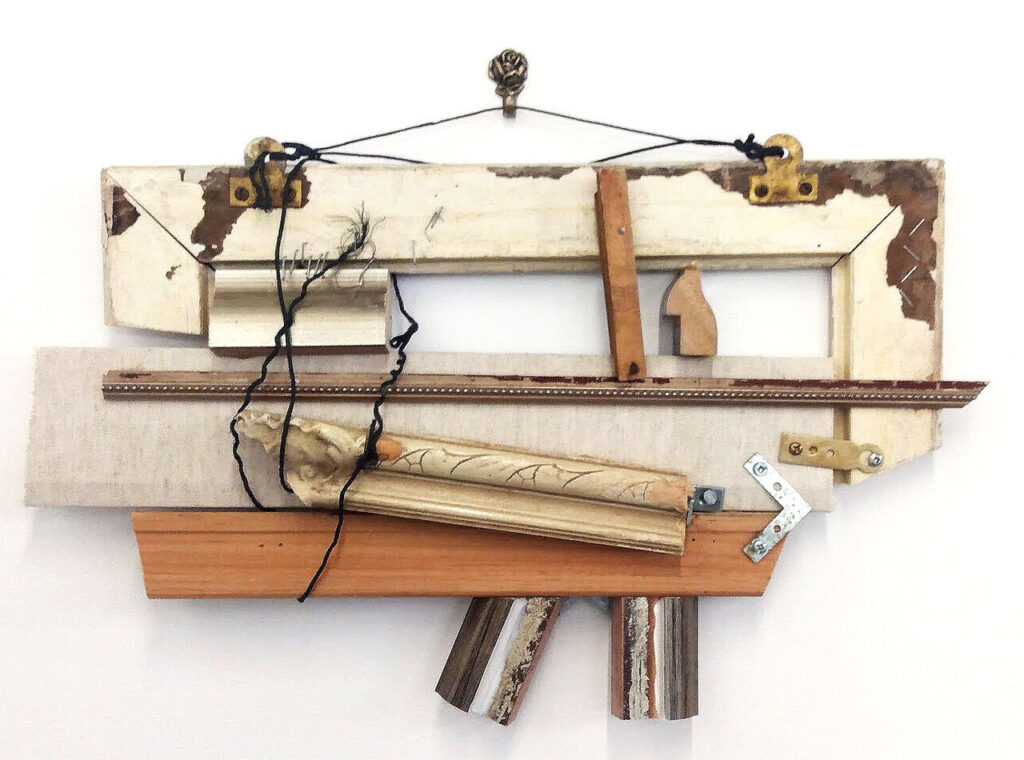

Indeed, the results of chaos can give rise to beauty. Purchase’s sculpture is a case in point. The detritus of broken picture framing is assembled into a delightful composition.

Sculpture by Doris Purchase. Photo: Hugh Alcock

We find a way to move on as Oates puts it. But notably Oates has refused to focus overtly on the current political chaos, which is so tempting to do. And this reluctance in part may be explained by the fact that she is an American, who must take as personal her country’s slide from political dysfunction into growing lawlessness. But inevitably, as we see in our discussion, everything is infected by the political in some sense.

Artwork by Yevgeniy Fiks. Courtesy of Station Independent Projects

I remarked earlier about Oates’ tireless promotion of independent artists. It seems to me at least she is motivated by a belief that art makes a difference, that is to say, society prospers only when art does. About this she is surely right. That is not to say a vibrant arts community is a sign of a prosperous society, but rather conversely a society can only be said to thrive when it has a vibrant arts community. One is here reminded of the zealous utilitarian schoolmaster Thomas Gradgrind in Charles Dicken’s novel Hard Times. Gradgrind represents the forces that dismiss artistic activity as a mere frill that no one really needs. But an economically prosperous society with little or no art leaves no room for us to express and explore our humanity. Oates has dedicated herself to promoting art for this reason.

Leah Oates in Remote Gallery. Courtesy of Station Independent Projects

Station Independent Projects and its ilk are vital to the cultural life of this city. This show has been a good example why. The Remote Gallery, warmly illuminated on an urban street dedicated to moving traffic efficiently, offers Torontonians a respite, a chance to take a breath and think about chaos – a topic that on the face of it seems arcane and technical, but which in fact informs much of our society. The range of art on display is diverse but focused. Let’s hope Station Independent Projects stages more shows like this around the city.

Installation view of Chaos Theory at Remote Gallery. Courtesy of Station Independent Projects

*Exhibition information: Chaos Theory/ Group show, Remote Gallery, 568B Richmond St W, Toronto. November 10 – 17, 2025. Organized by Station Independent Projects.