In the window of YYZ Artists-run Centre are displayed columns of subtly marked works on paper. Together they are an attractive array, but individually they are difficult to interpret. The viewer can readily identify the outlines of trees in a forest setting. But the thinking that guides their making is intricate and involved. The overarching idea behind the work is what its creator, Andrzej Tarasiuk, describes as the attempt to “convey the dynamic nature of place, not as a collection of individual elements but a complex interrelated network of relationships of which we are a part of.” This he does through what he calls the ‘lens of process’.

Installation view of Andrzej Tarasiuk. Broken Trees at YYZ Vindow

As he sees it, the reality he aims to depict is a dance of ‘actual entities’ – a term coined by the English mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. Whitehead saw the schools of rationalism and empiricism as conflicting views. According to rationalism our knowledge of the world ultimately derives from self-evident truths that we intuit, e.g., that two and two is four. By contrast empiricism holds that the only route to knowledge of the world is through our senses. Whitehead sought to create a metaphysical view that wedded these two schools of thought, that connected the outside world as we perceive it with the world as it is governed by reason, and hence amenable to our rational intuitions. To this end he invented the idea of actual entities.

Installation view of Andrzej Tarasiuk. Broken Trees, detail

Tarasiuk’s starting point is watercolour painting. While on a artist’s residency at Labverde in the Brazilian Amazon he began to mark his watercolour paper with the natural materials around him – mud, leaves and even river water. These marks became the grounds for his paintings. Back in Toronto Tarasiuk made visits to Etobicoke creek, and carried on this experimental process. He chose the theme of fallen or broken trees because he saw it as a manifestation of the perpetual life-cycle of the forest. The death of trees is as much a part of ‘life’ as the living ones. What’s more, in line with his Whiteheadian perspective, he sees the living forest as being autonomous. Everything in nature, by this measure, consists of actual entities which are defined by their autonomy. He writes: “Thinking about landscape as ‘becoming’ made me think about the agency land has in shaping itself, and human/personal agency in shaping the landscape.”

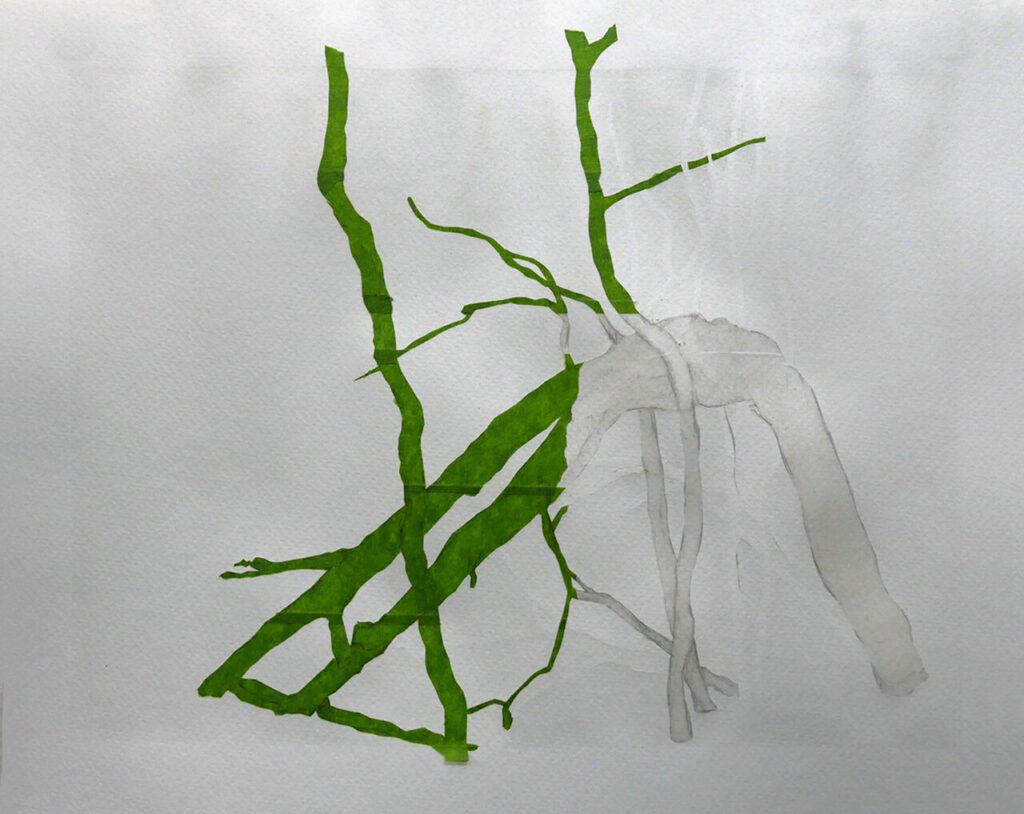

Etobicoke creek, 2019, chlorophyll, water, dirt, bark, art mask, tape on paper, 22cm x 36cm

The actual entities that Whitehead hypothesised are thought to ‘grasp’ the world both conceptually and sensually. Reality itself is described by the relations between all actual entities. Crucially, these relations are never fixed – they are always in a state of flux. That is, as he puts it, an actual entity “ always in the process of becoming and perishing…” (Process and Reality, p. 126). All told Whitehead’s view is rather implausible. For example, it assumes that even rocks are autonomous and have the capacity to relate to other entities both physically and conceptually. Nonetheless, from an ecological perspective Whitehead’s metaphysics is very attractive. It helps us to think of nature as a living whole, as Tarasiuk clearly does.

Broken Tree #24, 2019, chlorophyll, water, dirt, bark, art mask, tape on paper. 36cm x 22cm

His agential conception of natural phenomena leads Tarasiuk to think of forests as engineering their environment. For example, he learned in Brazil that trees can each release into the atmosphere up to a thousand litres of water per day. The whole forest, therefore, acts as what he describes as a biotic pump, transforming the climate. He imagined a whole ‘forest’ of mechanical pumps that might transform, say, a desert into a lush landscape.

Perhaps mirroring nature itself Tarasiuk’s artmaking is process driven. A stencil is made using masking tape on each piece of paper. It is then stained with creek water and various other natural materials found at hand, e.g., rubbed leaves. Then the stencil is partially removed. The results are beautiful images built from subtle layers of stain. The residual masking tape gives the image some visual impact. Tarasiuk confesses that he has been surprised how well the stains have lasted, given that he deliberately used fugitive materials in line with the idea of the continual flow of change in nature.

Broken Tree #4, Etobicoke creek water, Spring, 2019, art mask, tape on paper. 36cm x 22cm

While the defined process of using the natural materials around him provides the parameters that create the overall look of the images, what makes the images themselves captivating is Tarasiuk’s judicious choice of stencilling. As I have emphasized, Tarasiuk’s art is conceptual – his artmaking processes follow from how reality, as he puts it, is ‘constructed’ by us, by how we perceive the world. Nonetheless, much of what draws the viewer in are his personal aesthetic decisions. His use of a traditional watercolour-based medium points to the importance of the aesthetic here. This in the end, I think, is the greatest strength of his work.

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of YYZ.

*Exhibition information: Andrzej Tarasiuk, Broken Trees, September 18 – November 27, 2021, YYZ Artists Outlet, 401 Richmond Street., #140, Toronto. Gallery hours: 7 days, 24 hours