On the wall of the main gallery and its ante-room hangs a series of photographic tableaux. In the middle of the floor of the main gallery sits an installation sculpture in varying states of disassembly. As well, at the back there is another series of photographic tableaux, together with several mannequins, – or ‘animatronic figures’ as Dean calls them, – which are featured in these photographs. The theme of the show is Dean’s decade-long journey with prostate cancer.

In a humorous tone, Dean writes that his team – the gang from Ontario Place’s erstwhile Wilderness Ride, i.e., his animatronic figures rescued from there – have been enlisted to help him to explore possible cancer treatments. The figures appear alongside Dean and others in various of the photographs (which are done in collaboration with Andrew Savery-Whiteway). For example, they stand in as the audience in the centerpiece photograph Still – Agnew Clinic, based on a painting by Thomas Eakin of a surgeon’s demonstration. As well, in Meeting the Team, Dean is seen to be about to shake the hand of one of the figures while holding a bloodied replica of his prostate gland behind his back. The replica, made by a plastic 3D-printer and modelled on a scan of his actual prostate, is the central element in the works in the show.

Max Dean, Still – Agnew Clinic, 2020, pigment print on archival paper19 ¼ x 28 ¾ in

Max Dean, Meeting the Team, 2020, pigment print on archival paper, 19 ¼ x 28 ¾ in

In the centre of the room the visitor walks through the parts of the disassembled sculpture. When assembled the sculpture appears as a large boulder, in virtue of a painted tarpaulin cover. Underneath are several layers of construction. At its very heart sits a replica of the prostate surrounded by twigs and plastic plants. These are deposited in a bin which is cut down in the middle and placed on wheels. The outside of the bin is covered in bouquets of plastic flowers. And around this are placed a couple of domes, again on wheels. The inner dome is comprised mainly of draped clothes, and the outer one of books and cardboard boxes, along with other domestic items. There is online a video featuring Dean and his assistant, McAlister Zeller-Newman, taking off the cover and wheeling the sculpture apart. This room-sized sculpture, Dean tells us, represents his tumor. Clearly it does so as a psychological phenomenon rather than physically, reflecting the fact that the show’s theme is Dean’s coming to terms with the disease.

Installation view of Max Dean: Still – Living Through Cancer and Covid at Stephen Bulger Gallery

Through the exhibition Dean relates his personal journey with cancer, and as such the work is autobiographical. He is upfront about his disease and is willing to pose in uncomfortable situations in the photographs, e.g., in Suppository. He leaves little distance between the viewer and himself in this respect. Why is he so candid? Certainly, in conceptual art the body often plays a central role, and indeed that is true of other works by Dean. But more generally, one needs to appreciate that Dean’s art and his life cannot be separated.

Max Dean, Suppository, 2020, pigment print on archival paper, 19 ¼ x 28 ¾ in

Even a cursory survey of his career reveals that he is constitutively compelled to make art. The creative process is innate to him. He incessantly turns his life into art. The only way I understand this compulsion is by relating it to Friedrich Nietzsche’s notion of art as life affirming. As he saw it, artists are intoxicated by life – an intoxication (Rausch) through the senses. The artist as such instinctively aims at life, embraces it. For Nietzsche this drive defines the artist – the artist’s exercising of his will.

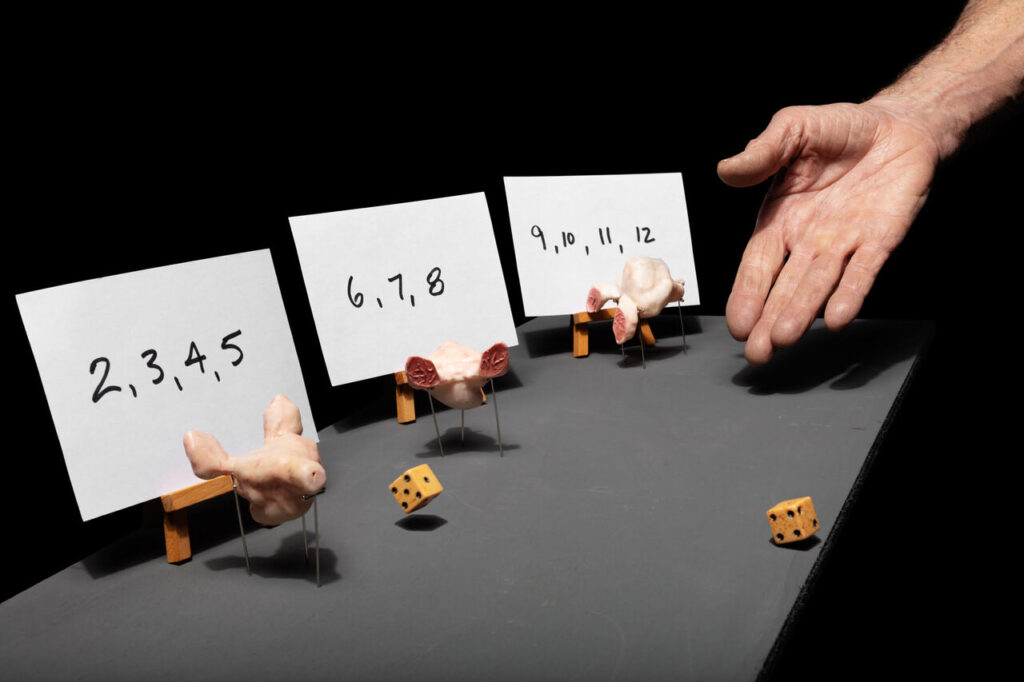

Like living itself, Dean understands art to be inherently risky. An introduction to a previous exhibition (I’m Late, I’m Late at Stephen Bulger Gallery, 2016) reads: “Come and join Dean’s journey to the edge of his jungle, ride along perilous mountain roads, walk to the edge of cliffs, and cross vast bodies of water teaming (sic) with ravenous creatures.” Life’s adventures for Dean are through the artistic process. But as he admits, cancer is of a different order. It is, as he puts it, ‘thrust upon us’. Indeed the notion of aleatoric chance as something outside of our own control, of our willing, is addressed by Dean in his Rolling Dice For a Prostate. Even so, Dean aims to conquer the disease psychologically by his art – ‘bringing it over to the positive side’ as he puts it.

Max Dean, Rolling Dice For a Prostate, 2020, pigment print on archival paper, 19 ¼ x 28 ¾ in

His intoxication with life helps to explain the optimistic tenor of his show despite its theme. Dean recounts that his doctor told him that he is likely to die of something else before the cancer kills him. Nonetheless, the diagnosis augurs his end, albeit not imminently. In a soon-to-be-released film, Max Still, produced by Katherine Knight, that documents the making of the pieces for this show, Dean reveals this optimism by his very struggle to express it. He observes that every film has a temporal ending: “the projector is going to get turned off, there’s no more footage and the story is over.” But he then adds that he doesn’t want it to end, that somehow he won’t end it. There is no ending, he concludes. While this thought is literally self-contradictory it still expresses a genuine feeling.

Installation view of Max Dean: Still – Living Through Cancer and Covid with Caged, 2021, collaboration with Andrew Savery-Whiteway (in the center)

Hugh Alcock

Images are copyrighted Max Dean/courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery

*Exhibition information: Max Dean: Still – Living Through Cancer and Covid, May 1 – August 28, 2021, Stephen Bulger Gallery, 1356 Dundas St. W., Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat 11 am – 6 pm or by appointment. The exhibition is part of Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival.