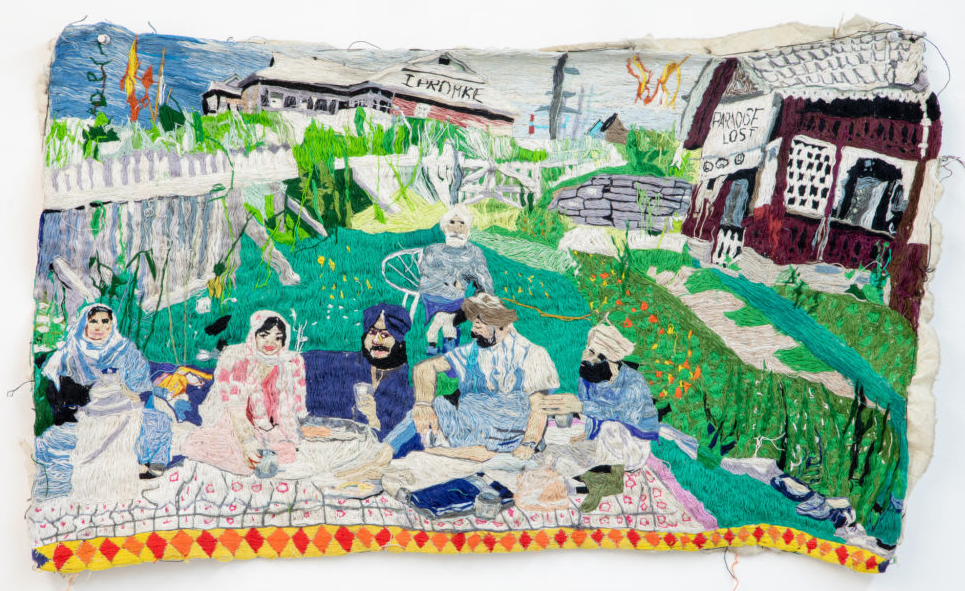

Two women and four men, one older than the rest, lounge atop a picnic blanket over bright green grass. They’re holding glasses, dressed in flowing garments of blues and pink. They look serene. This is surely a family portrait. The easy way about this cartoonish crew is too good – it’s gotta be a memory. In the distance, out behind the yard, there’s a building with the title “I PROMISE” stitched on its roof. The house on the right says “PARADISE LOST,” with a few shotty frowny faces done underneath for good measure. It’s never written right there explicitly, but you recognize this is a home left behind.

Jagdeep Raina, Paradise Lost, 2019, embroidered tapestry and

Punjabi phulkari border on muslin, 18 x 30 in. Courtesy of Cooper Cole

“Paradise Lost” (2019), an embroidered tapestry made with Punjabi phulkari is the first work you see when you walk into Jagdeep Raina’s exhibition I Promise at Cooper Cole. Phulkari, meaning floral work, is type of South Asian garment, textiles embroidered with flowers made for everyday wear, like scarves and shawls. Phulkaris from the Punjabi region have wide edges, as in the diamond pattern dancing underneath this picnic scene. The material signifies its regional origin, establishing setting. “Paradise Lost”, this image of a family before the rest of Raina’s exhibition, which are mostly pictures of cityscapes, situates us in a story about migration, the feeling of moving away from home. Clothing is cultural, but it’s personally meaningful too, symbols of private sentiment (this is what I wore when X happened, etc.) “In dressing myself, I embellish that which, by desire, will be spoiled,” writes Roland Barthes in A Lover’s Discourse (1977). Dressing myself transports me elsewhere, like to a family picnic in my old backyard, a time I was probably happy. But the edges of “I PROMISE” are frayed, like the whole picture could unravel if you aren’t careful.

Installation view with Jagdeep Raina, Paradise Lost (left) and You migrate, we migrate, you displace, we displace (right). Courtesy of Cooper Cole

Why would you ever make a promise? “I promise,” is one of those horrible declarations that, once spoken, foreshadows its own let down. You probably meant it when you said it. A set up for failure. In promise there’s hope, trust, futurity, what Lauren Berlant calls cruel optimism.

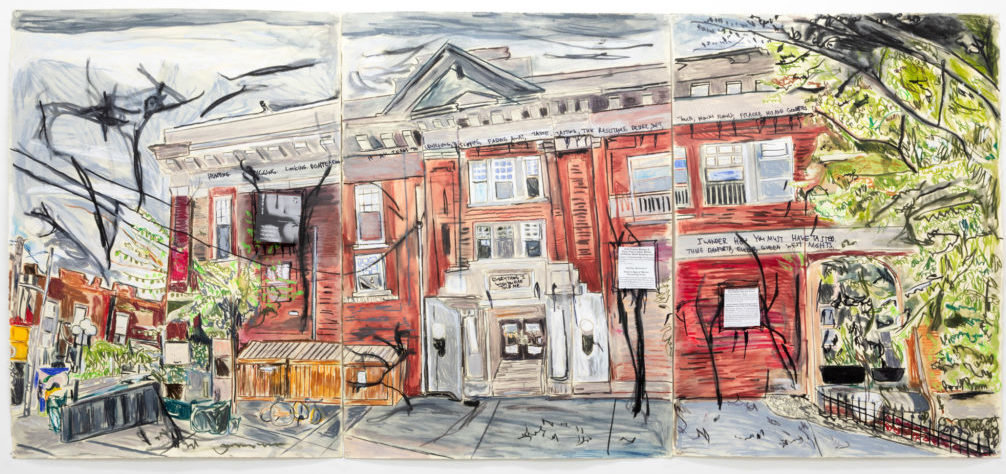

Jagdeep Raina, Everything I Wish You Had Told Me, 2019,mixed media on paper, 30 x 66.5 in. Courtesy of Cooper Cole

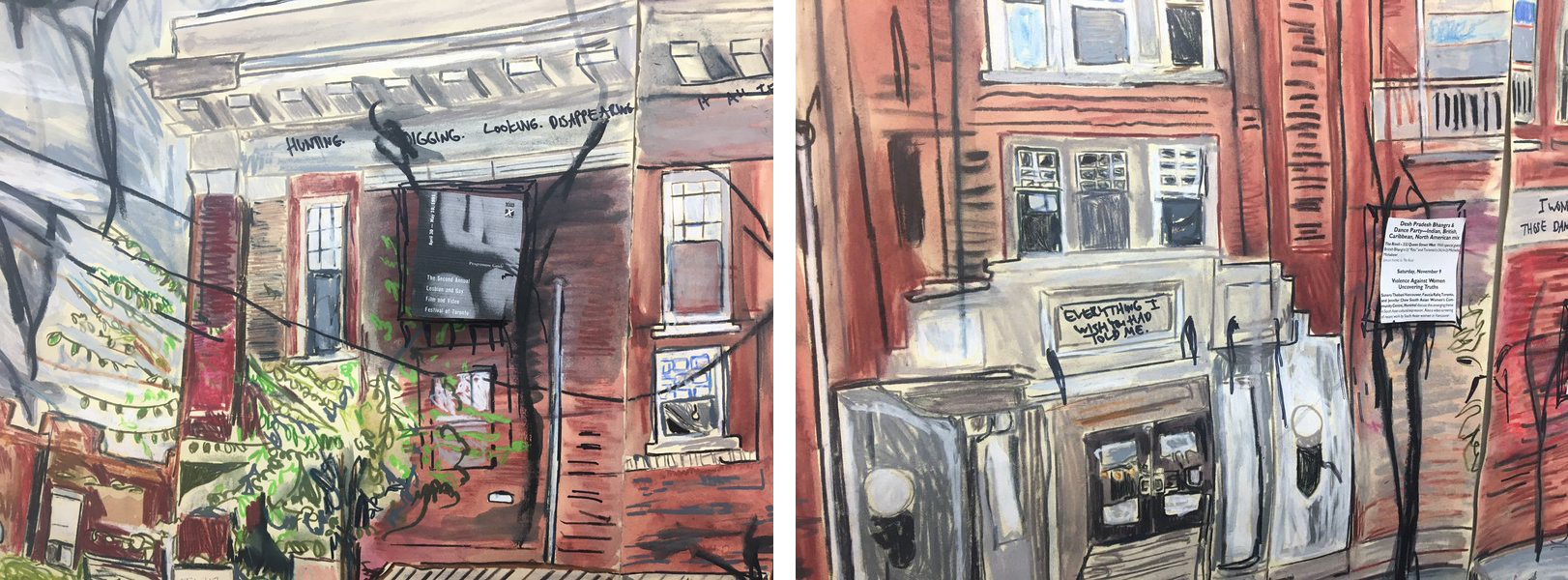

Well if you’re sentimental about clothing, you probably feel the same about place (this is where I was standing when you said X, and so on). “Everything I Wish You Had Told Me”(2019) is a painting of a building, on three sheets of paper. Found texts from flyers, pamphlets, and programs are pasted on as if they belong to this building like windows. They say things like: A presentation looking at the construction of identities by South Asian lesbians and gay men and how we use personal, social, and archeological histories in order to construct who we are and our desire for communities. They’re headlines about the AIDS crisis, and programmes from a queer film festival. You collect images of yourself, clues of a personal history found in tokens from public programming and clippings about politics. These are, to borrow a cliché, of course also personal. Collage is the sentimentalist’s natural medium. The sentimentalist pockets things like flyers, movie-stubs, wrappers. And the sentimentalist, prone to endowing objects with magic, can be a fetishist. Written on the right side of the building is the phrase “I WONDER HOW YOU MUST HAVE TASTED. THOSE DANFORTH, EUCLID, QUEEN WEST NIGHTS.” I have streets too: Bathurst looking south, College facing east where the clock tower looks like the moon, the northwest corner of Bloor and Spadina.

Jagdeep Raina, Everything I Wish You Had Told Me, 2019,mixed media on paper, 30 x 66.5 in, details. Photo: Chelsea Rozansky

“& I’ve seen Paradise and it had four walls & man, we used to dance all night,” writes Cameron Granger in his exhibition text. “Used-to-bes atop of used-to-bes,” Granger writes, naming buildings that have been torn down, places long gone. For instance “The park where I had my first kiss is a used-to-be now.”

One summer, now a long time ago, I kissed a boy at a construction site that used to be a playground attached to my elementary school. “This is weird place,” he said, by betrayal. “Yeah,” I jokingly agreed, “my childhood is ruined.” One year later, I ran into him as I was on my way home to my parents’ house. It was late at night and I was wearing my favorite pants and riding my old bike. We stayed up all night talking and laughing and making imaginary plans, and the whole time I felt so sad because I knew that night would end.

Jagdeep Raina, You migrate, we migrate, you displace, we displace, 2019, mixed media on paper, 40 x 77.5 in. Courtesy of Cooper Cole

“& that place isn’t our place anymore & I’m not sure I could even find my way back, writes Granger, about paradise. So what does it mean if you’ve seen paradise and it tasted so good, but you knew it’s a promise about to break, already lost?

Chelsea Rozansky

*Exhibition information: October 25 – December 21, 2019, 1134 Dupont Street, Toronto, Gallery hours: Wed – Fri, 12 – 6 pm, Sat 11 – 6 pm.