“Death is nothing to us,” said Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius, meaning, among other things, that there’s nothing frightful in being dead, since death by definition involves complete annihilation of the subject of experience. This argument, and its ability to comfort in passing and bereavement, has sat better with some generations than others. And treatment of death in visual art tracked these varying attitudes towards mortality. Michael Wolgemut’s Danse Macabre, produced amidst the horrors of post-plague Medieval Europe, cries out with disconsolate tanatophobia. Pierfrancesco Cittadini’s Vanitas, representative of the Early Modern overthrowing of Medieval conventions, goes to another extreme, making death conspicuously fashionable. Somewhere in between on this attitudinal scale lies Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead, where, expressive of the fin-de-siècle anxious fascination with the otherworldly, an ominous trip to the underworld is surrounded with objects of décor befitting a picnic at a Mediterranean coast.

Installation view of Spring Hurlbut’s A Fine Line, Georgia Scherman Projects, 2016. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

Installation view of Spring Hurlbut’s A Fine Line, Georgia Scherman Projects, 2016. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

Spring Hurlbut’s A Fine Line, exhibited at the Georgia Scherman Projects, includes a 2005 photograph (Deuil I: James # 2) which features a composition highly reminiscent of vanitas paintings in their numerous variations. A bag of human ashes on a dial scale – a contemporary analogue of the Early Modern scull next to an hourglasses, – aside from establishing a departure point of Hurlbut’s engagement with her morbid medium, provides a welcome interpretative key to her approach to artistic depictions of death. A Fine Line makes death acceptable and even fashionable in an aesthetically pleasing, technically sophisticated, and meta-artistically rich way.

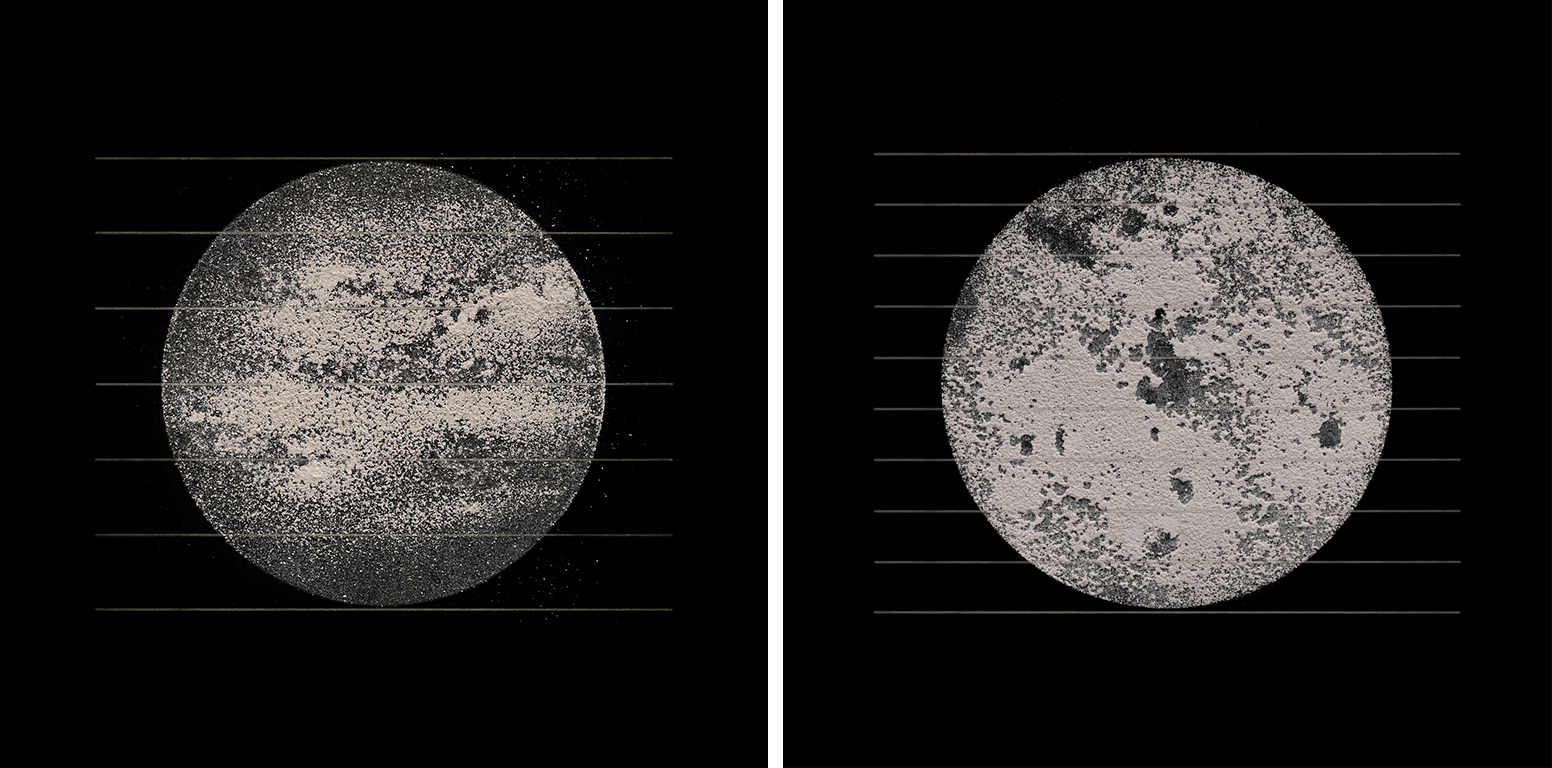

Spring Hurlbut, Arnaud #4 (left), and #5 (right), both 2016, 27 7/8 x 27 7/8 inches framed, archival pigment print, edition of 3. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

Spring Hurlbut, Arnaud #4 (left), and #5 (right), both 2016, 27 7/8 x 27 7/8 inches framed, archival pigment print, edition of 3. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

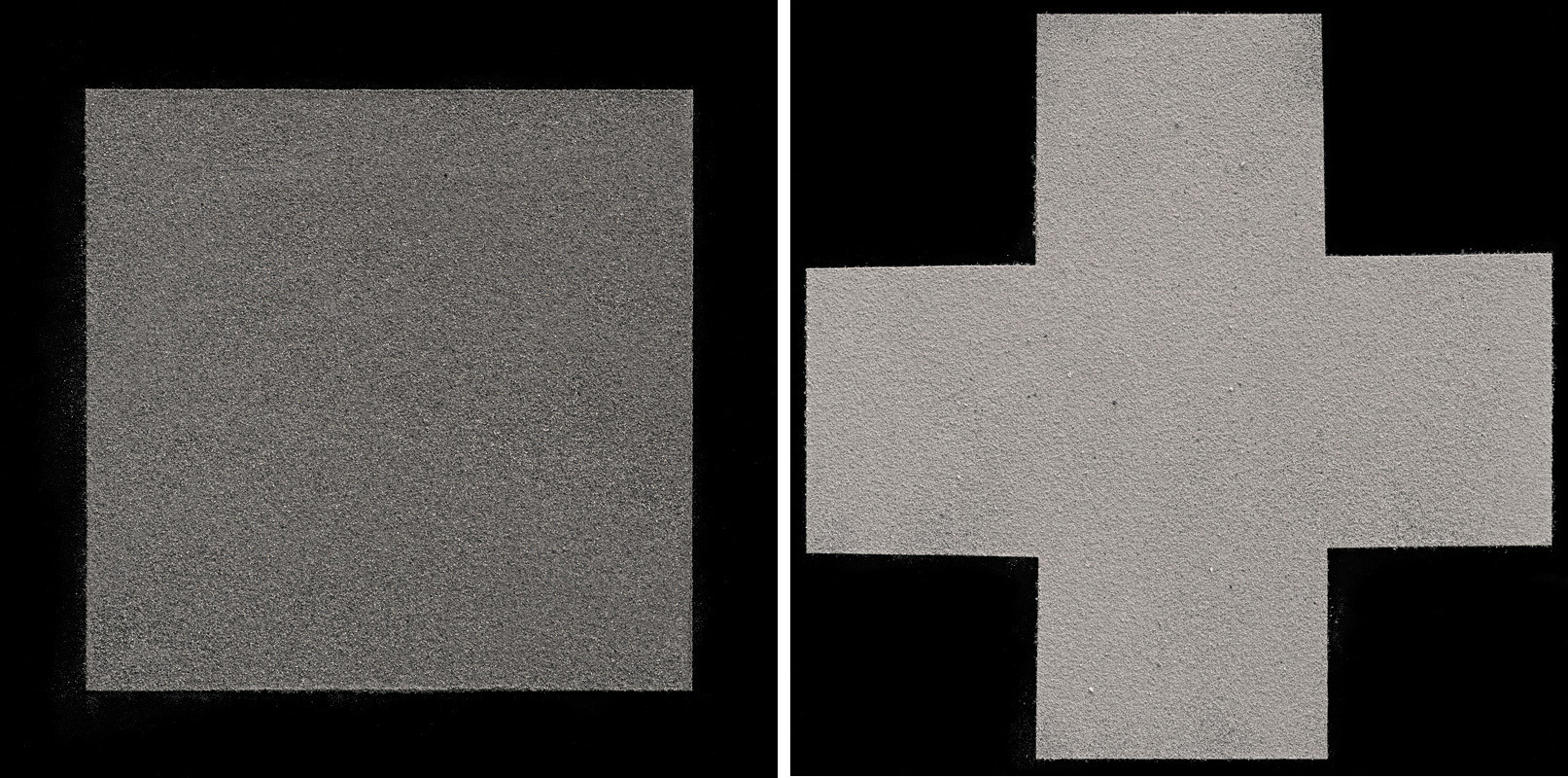

There is no fault in rendering death as fashionable, when it is done overtly; in Hurlbut’s works, such conspicuousness protects against pathos and heavy-handed symbolism, extinguishes the viewer’s desire to read too much into these celestial bodies, puffs of smoke or geometrical figures made of human and animal ashes. The gallery’s setup, minimalistic but hardly sombre, and certainly not morose, is conducive to interpretative restraint. Explaining the exhibition’s background, Georgia Scherman, the gallery’s friendly owner, does not press on symbolism, but emphasizes the meta-artistic connections to vanitas and memento mori, to abstract icons of Kazimir Malevich, but also to purely formal experiments of Agnes Martin.

Spring Hurlbut, The Malevich Suite: Nutmeg #3 (left) and #2 (right), 2013, archival pigment print, 18.5 x 18.5 inches, edition of 3. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

Spring Hurlbut, The Malevich Suite: Nutmeg #3 (left) and #2 (right), 2013, archival pigment print, 18.5 x 18.5 inches, edition of 3. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

And once the temptation of the symbolic is done away with, and the curiosity regarding the meta-artistic is satisfied, one begins to notice peculiar artistic challenges arising from Hurlbut’s choice of medium. There is nothing stylized about her photographs; ashes, despite being arranged in various ways, are easily identifiable as ashes. Historically, some of the most realistic death-related artworks and works of design, from the bone chandelier in Sedlec Ossuary to the contemporary Body Worlds exhibition, used real human remains. However, human and animal ashes, loaned to Hurlbut, had to be returned to grieving families and owners. Moreover, unlike bones and soft tissues, ash is a capricious and delicate material that it hard to paste onto a collage, and nearly impossible to preserve intact. How does one render theme in photography as realistically as possible?

Spring Hurlbut, Deuil I: James # 2 (part of), 2005, archival pigment print, 24 3/8 x 30 inches (left); and Deuil II: Grania and Robert #2 (ruler), 2006, archival pigment print, 24 1/2 x 45 inches (right). Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

Spring Hurlbut, Deuil I: James # 2 (part of), 2005, archival pigment print, 24 3/8 x 30 inches (left); and Deuil II: Grania and Robert #2 (ruler), 2006, archival pigment print, 24 1/2 x 45 inches (right). Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

This is where Hurlbut’s artistic ingenuity comes into play. Some of her newest photographs depict ash placed over thin, soft parallel lines somewhat reminiscent of musical scores; these lines are clearly referred to in the exhibition’s title. Their visual function, apparently, is to emphasize texture, and they do so to the point where, at least from a distance, these photographs look like collages made with real ash. There is a mild geometrical-optical depth perception illusion at work here, something akin to the Orbison or Ponzo effect. Technical nuances of this sort keep the fashionability of death in Hurlbut’s works safely away from moribund New-Agey kitsch; but even here the viewer must be aware of unexpected traps. As we contemplate the effect of this illusion on our depth perception, we might find it hard to refrain from symbolic attributions, to forbid ourselves from interpreting photographs as allegories regarding an illusory nature of life, death, or all of the above. But there are no allegories among ashes – only media for art.

Spring Hurlbut, Bert #1, 2016, 27 7/8 x 27 7/8 inches framed, archival pigment print, edition of 3. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

Spring Hurlbut, Bert #1, 2016, 27 7/8 x 27 7/8 inches framed, archival pigment print, edition of 3. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects

Andriy Bilenkyy

*Exhibition information: October 20 – November 26, 2016, Georgia Scherman Projects, 133 Tecumseth Street, Toronto. Gallery hours: Gallery hours: Wed – Fri 10 am – 5 pm, Sat 11 am – 5 pm.