Upon entering The Culture, Hip-Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century exhibit at the AGO, visitors are welcomed with heavy rap beats and rhythmic flow, creating excitement and anticipation. Hip-hop is culture and culture inspires all aspects of life. The music, photography, film, fashion, politics, and art, of the exhibition embodies hip-hop culture through an immersive experience. Divided into six themes—language, brand, adornment, tribute, pose, and ascension—that speak to the foundation of hip-hop, visitors are asked to navigate the exhibit using all their senses.

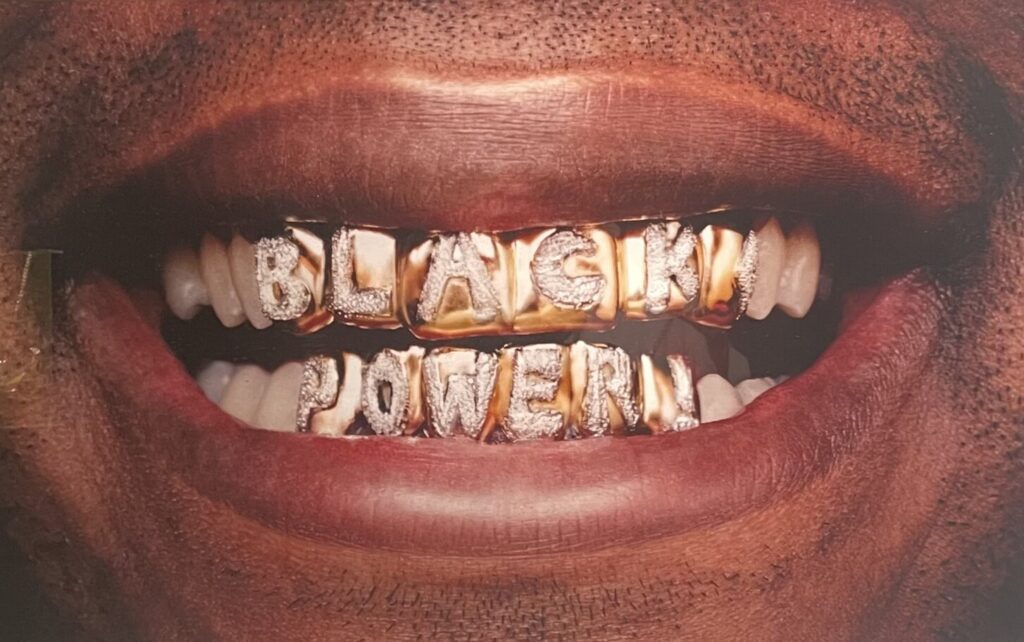

Hank Willis Thomas, Black Power, 2006, chromogenic print, digital exposure

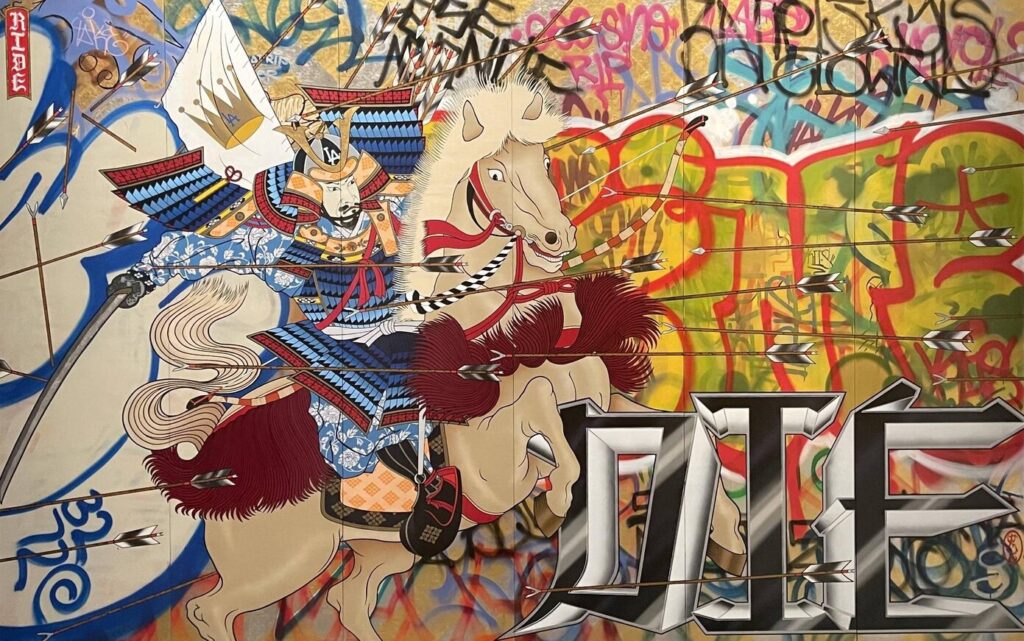

We are greeted with a visually packed piece inspired by both street and Japanese art. Originating from an economically depressed area in the Bronx of New York City, hip-hop has become a cultural phenomenon, a movement that inspires and engages individuals from all different backgrounds. In this piece, we are faced with two different cultural facets: graffiti such as cholo writing and fill-in throw ups from ‘90s LA street culture and the use of gold leaf from Edo-era Japan. Engulfed in overlapping graffiti using various colors and fonts, a glorious Edo-era samurai is captured soaring through it all as arrows rain down on him and his horse. It is as if the samurai broke through the barriers of time, emerging from Edo-era Japan into the streets of East LA’s Latino neighborhoods. Through close inspection, an LA Dodgers’ logo is engraved on the samurai’s otherwise traditional helmet, known as kabuto, carefully intertwining the two vastly different cultures to capture the artist’s identity. The work not only captures the fusion of cultures that the artist embodies but the bond that formed between two art periods, elevating graffiti into the world of high art.

Gajin Fujita, Ride or Die, 2005, spray paint, paint marker, paint stick, gold leaf on wood panels

Bordering the world of high art and its established mediums is fashion; a wearable manifestation of art. Within the realm of hip-hop, fashion is a proud form of identity and self-expression, usually baggy jeans, big t-shirts, and body-hugging tank tops, paired with loud accessories, hats and bandanas, and the trendiest sneakers. But as hip-hop grew and absorbed other ethnicities, each bringing their own customs and styles, the uniform was reinterpreted in various ways. Baby Phat by Kimora Lee Simmons, who was the wife of hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons, brought a touch of female empowerment, luxury, and street style to the iconic velour tracksuit in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Worn by celebrities such as Lil’ Kim, Missy Elliot, Alicia Keys, Foxy Brown, and Beyoncé, this tracksuit was a status symbol, establishing itself in high-end retail and pop culture. American designer Willy Chavarria, with roots in Mexico, brings a contemporary look to the bold and oversized aesthetics prized in hip-hop culture. This look blends streetwear with luxury and Chicano influences, modernizing ‘90s and 2000s baggy with freshness and tailoring.

Kimora Lee Simmons, Baby Phat, around 2000, tracksuit, cotton (left) and Willy Chavarria, Buffalo Track Jacket and Kickback Pant, spring/summer 2022, nylon satin (right)

Clothes are not the only wearable art that hip-hop celebrates. Wigs, especially Dionne Alexander’s wigs, not only helped change hip-hop but evolved it into a category of its own. Bringing iconic rapper Lil’ Kim’s colorful personality to life, these wigs by Alexander helped create a chameleon that matched her provocative lyrics and monochromatic outfits. Brand logos are a big part of hip-hop culture, serving as symbols of status, and Alexander understood the assignment when she dyed, imprinted, and stenciled some of the biggest brand logos onto her wigs. She was, after all, styling the hair of one of the biggest hip-hop stars of her time. It was either be bold and be a trendsetter or stay hidden amongst other rising stars. These wigs cemented Lil’ Kim’s name in hip-hop history and established her identity on the world stage.

L-R: Lil’ Kim photographed by David LaChapelle in Interview Magazine, November 1999, Dionne Alexander, Lil’ Kim Chanel Logo Wig, 2001, recreated 2022, human hair wig, Lil’ Kim Purple Wig from MTV VMAs, 1999, recreated 2022, synthetic hair wig, Lil’ Kim Versace Logo Wig, 2001, recreated 2022, human hair wig, Lil’ Kim Zipper Wig from MTV VMAs, 2001, recreated 2022, human hair wig, zipper and Lil’ Kim photographed by Clay Patrick McBride in XXL Magazine, May 2000

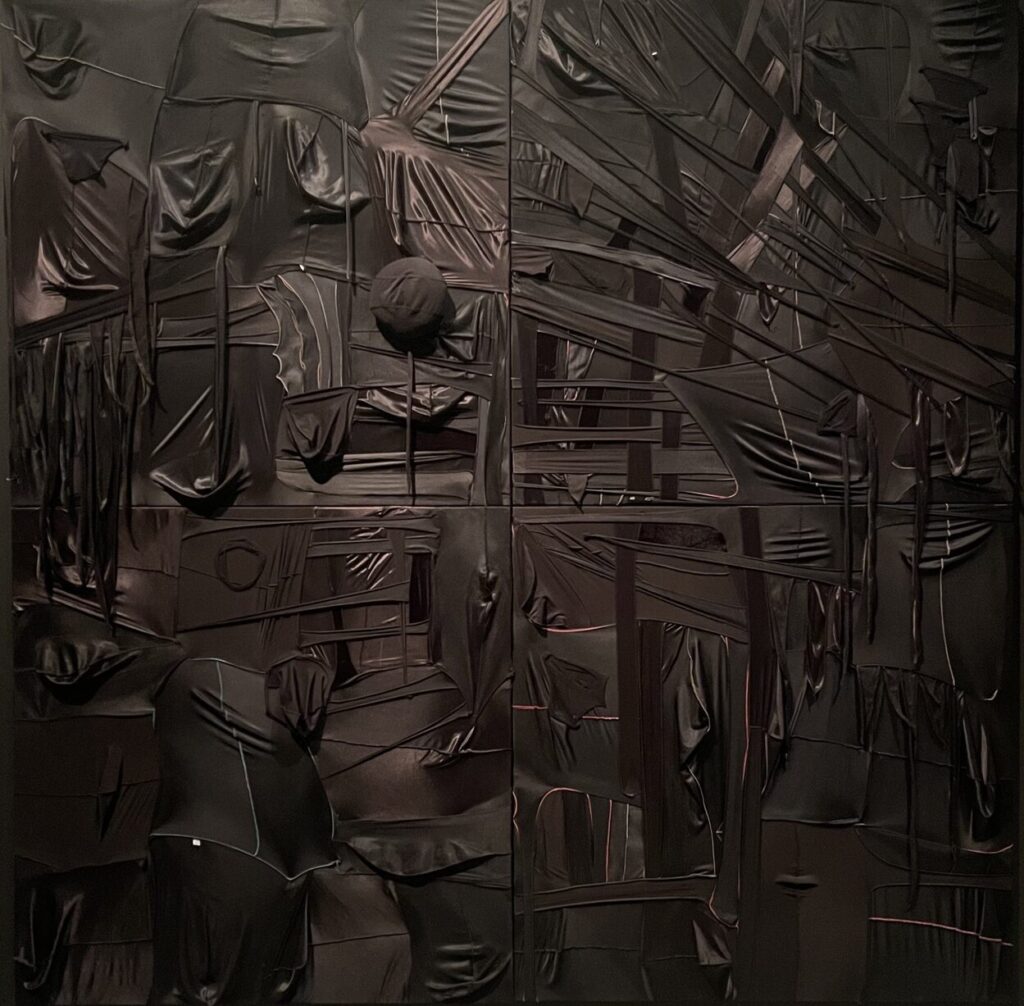

Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola’s abstract durag work encompasses a collage of black durags cut, stretched, and stitched into a dynamic composition. This flexible headscarf is used to maintain hairstyles like waves and braids, becoming a symbol of Black self-care and grooming. It is a tool used for preservation of cultural hairstyles and a resistance to Eurocentric beauty standards. Traditionally associated with street culture, it was seen as a symbol of rebellion against systemic oppression with its defiant and criminal connotations. The work incorporates street culture onto a fine art canvas, creating a beautiful composition mirroring abstract oil on canvas works, breaking boundaries between high-end and low-end, bringing Black heritage to a traditionally European medium. Hip-hop icons such as Jay-Z, 50 Cent, Nelly, and Cam’ron made durags a staple in hip-hop fashion as a statement of confidence, swag, and status.

Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola, CAMOUFLAGE #105 (Metropolis), 2020, durags and acrylic on wood panel

In his showstopping piece, artist Aaron Fowler uses recycled car parts and other media to create this large sculpture of Nike Air Force 1 sneakers. Its monumental scale speaks to the power of these sneakers and their influence in hip-hop fashion, connecting his personal biography and Black cultural heritage. Nike Air Force 1 immediately became a staple in hip-hop fashion, embraced by rappers, streetwear enthusiasts, and sneakerheads. From rappers to high-end brands, Nike has collaborated with countless industry leaders on making variations of Air Force 1s. The innovative use of recycled car parts speaks to the artistry of black artists, finding inspiration from their personal life and the culture they grew up around. The white and blue splotches on the base emphasize the clean and simple silhouette of the sneakers, highlighting their versatility, which made them a perfect fit for any style: streetwear or luxury. It is seen as a cultural artifact of hip-hop, representing self-expression, street credibility, and timeless style, making them one of the most coveted shoes in hip-hop.

Aaron Fowler, The Live Culture/Nike Air Force 1, 2022, car parts, mixed media (in front)

The exhibition celebrates the 50th anniversary of Hip Hop culture. Featuring music, paintings, sculptures, photography, videos, everyday objects, multi-media installations and fashion, the show offers viewers a more complete understanding of that era. It also refers to political activism as well as racial and gender identities.

Text and photo: Sherry Qin

*Exhibition information: The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century, until April 6, 2025, Art Gallery of Ontario, 317 Dundas Street West, Toronto. Museum hours: Tue and Thurs 10: 30 am – 5 pm, Wed and Fri 10:30 am – 9 pm, Sat and Sun 10:30 am – 5:30 pm.