The current display at Christopher Cutts Gallery is the second part of a show of the late painter Rae Johnson’s work. The first instalment, titled Angels and Monsters, featured her early figurative work. Staged in the middle of the COVID pandemic viewings were limited to by appointment. Johnson was very ill at the time, and died barely a month after the show closed. That was close to five years ago now. So in a real sense this is only nominally the second part of a show. But the hiatus is fitting, given that this gap in time reflects the radical shift in themes that separates her later nature-based work from that done earlier in her career.

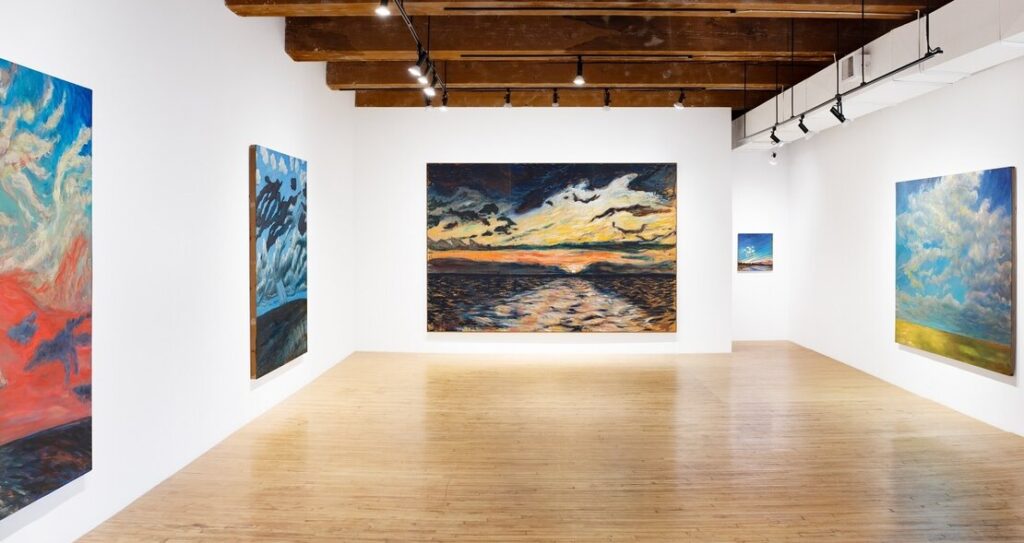

Installation view of Of Light and Darkness: Water, Land and Sky Paintings 1988-2008 at Christopher Cutts Gallery

The contrast is stark. Her early urban-based work features denizens of artificially lit interiors, especially bars and domestic rooms. These later paintings feature elemental landscapes with nary a soul in sight. There is, naturally, a continuity in her signature style across these bodies of work. But the change was radical enough that at the time she worried that the public would reject her new landscapes. After all, she was enjoying much success. But her worries were allayed. As is evidenced in the selection of landscapes on display here, her new paintings were, superficially at least, anodyne in comparison to her often disturbing quasi-punk urban-based work.

Lake Winnipeg, 1995, oil on board, 24 x 24 , inches

But, just as there is a dichotomous tension in her earlier work, so there is in her ‘nature paintings’, as she preferred to call her landscapes. Hence the show’s title Of Light and Darkness. An abiding preoccupation in her work is the blurring between the physical and the psychical. Influenced by the writings of Carl Jung, Johnson came to feel that the difference between these two metaphysical categories is largely illusory. They are aspects of a single reality. And indeed, looking at these paintings one gets the sense that they each represent an interior psychic landscape projected onto an outside world. One might describe her work as ‘spiritual’, and in general it is imbued with a religiosity.

Aurora Green Swoop, 2009, oil on board, 76 x 96 inches

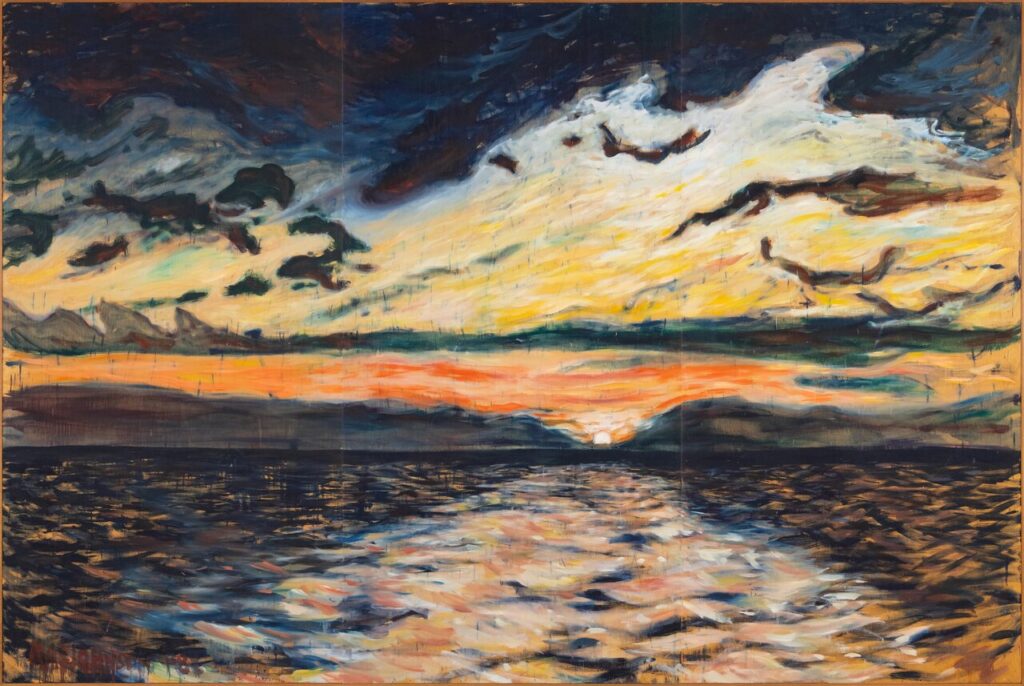

Ironically, while her landscapes betray an inner psychical world, they are based on close observation of nature. Crucially, however, it is the light that interested her the most. She wrote: ‘They are observations of the cycle of light and darkness, the movement of the wind and the elements over the sky, earth, and water’. Indeed, rarely did she depict details in nature. In these paintings trees are most often rendered as dark clumps on the distant horizon. Her focus, rather, is on the timeless qualities of nature that belong to the elements. She compared her paintings with musical compositions, and saw them as such primarily as expressions of emotion, i.e., her feelings. Her incessant study of nature – sometimes daily paintings of her pond or Lake Winnipeg – are in essence études using the visual notes of natural light and colour, from which she composed these larger paintings.

Firebird, Lake Winnipeg, 1998, oil on panel, 84 x 72 inches

Many of the paintings on display are large indeed, measuring up to twelve feet in length. Her bold signature at times spans nearly two feet, but remains inconspicuous because of the work’s sheer size. The scale reflects the physicality of her work. She describes how she would climb a ladder to reach, and on occasion attach large painter’s brushes to sticks in order to be able to stand back and see the whole painting while working on it. And always there is an urgency in her brushstrokes, as if there was too little time for her to capture what she wanted to express. Heraclitean at heart, Johnson saw the world as in constant flux; hence her fascination with nature in its elemental forms – sky, and water and land, which are both treated as a dappled screen, brushed by everchanging winds, and upon which light filtered by clouds flickers. Hers was an almost crazed desire to capture these ephemeral phenomena, fix them in static paint. It is this desire that betrays the feeling of urgency in her brushwork. The scale accentuates this feeling, makes it real.

Sunset, Lake Winnipeg, 1988, oil on wood, 96 x 144 inches

The skies, which are predominant in these landscapes, are populated with fantastical cloud formations – sometimes reminiscent of a spider’s web, and at other times of a battleship. All seem dream-born, and yet still plausible somehow. It is as if she is depicting the gods shapeshifting in the guise of clouds – there as the menacing clouds in her “Selkirk Tornadoes”, Jupiter sits, ready to smite. It reveals Johnson’s awe of nature, its sublimity. She saw through the physical phenomena in nature to its eternal, dare one say divine, underpinnings. And the nature she depicts is both redemptive and cruel. Its darker side is also evident in these landscapes, all of which links to our inner psychical worlds.

Selkirk Tornadoes, 2007, oil on board, 72 x 84 inches

What is still so refreshing about Johnson’s work is its honesty, its sheer immediacy. There is not a hint of intellectual conceit in her work. She once described how she was inside her painting while working on it. That is the right metaphor. One could imagine her still momentarily residing there, behind those vaporous clouds.

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery.

*Exhibition information: Rae Johnson, Of Light and Darkness: Water, Land and Sky Paintings 1988-2008, January 11 – 25, 2025, Christopher Cutts Gallery, 21 Morrow Ave, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat 10 am – 6 pm.