At its modestly sized location on the ground floor of the 401 Richmond building, the Museum of Toronto is currently staging an exhibition that highlights the city’s wildlife, both flora and fauna. The curators have divided Toronto’s wildlife environment into three types: the shorelines of the rivers and lake, the ravines and parks, and the urban landscape of the streets. The exhibition is far from comprehensive. Nonetheless it features a great variety of plants and animals. They are mostly those we are conscious of, e.g., racoons, coyotes, pigeons and commonly found plants.

Entrance to the exhibition Toronto Gone Wild

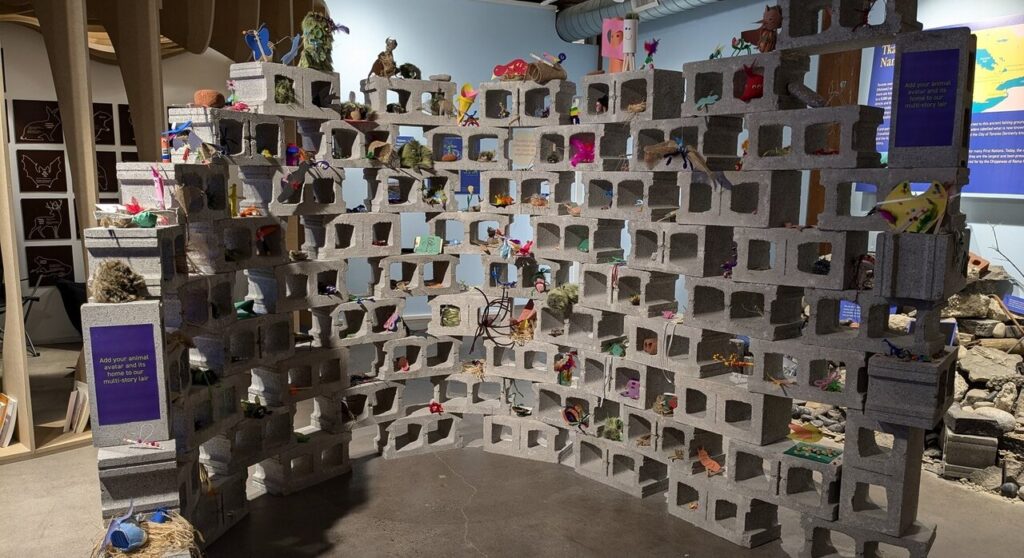

The overall theme of the exhibition is our relationship with our immediate natural environment, where the curators, for example, highlight some of the similarities we share with the wildlife, such as our common need to construct dwellings. On one of the many posters on display, titled ‘How We Dwell’, it is remarked that ‘many birds, insects and different types of mammals, like humans, live collectively’. This poster accompanies a wall-mounted display in the shape of a bee-hive, each compartment of which houses a picture or example of an animal’s habitat, e.g., a bird’s nest. As this instance suggests, there is a didacticism to the exhibition, which fits with perhaps one of its principal target audiences, namely children. All the same, the visitor is not treated as a school child. The overall tone of communication is suitable adult.

Dwellings

The animals we encounter, of course, are those who have adapted to the urban environment. Throughout there are hints at how radically we colonisers have altered the environment. For instance, we learn that the indigenous passenger pigeon, who once flew over the land in flocks numbering many millions, have been made extinct by us. The last recorded one died in 1914. All the pigeons we see today are descendants of pigeons brought over from Europe. As well, we learn that the honey is not indigenous to Canada. It too was imported.

Pigeon Display

One of the most impactful exhibits is a stuffed coyote. Lying in a mock-up of a den, this victim of the taxidermist is surrounded by posters offering factoids about this American species of wild dog. We learn why it has earned the epithet ‘wily’, viz., in virtue of the species’ capacity to adapt. We discover that after they almost met the same fate of the passenger pigeon, the coyote expanded their territory north-eastward, interbreeding with wolves en route. Now they are no longer an endangered species, despite their being a nuisance to farmers and pet owners alike. Indeed, their presence among us is beneficial in many ways, e.g., in keeping down the population of rats – one of their favourite prey.

Coyote display

In the far corner of the exhibition there is a nook. The visitor is encouraged to take a seat there, pick up a tag and write out a brief anecdote about her encounters with racoons in the city. Reading through some of the numerous contributions, I noticed a common theme to many of the anecdotes. Often the writer refers to racoons as thieves, as stealing this or that from them. I found this allusion both amusing and telling. Clearly a racoon is incapable of stealing given that it has no concept of property. But such comments demonstrate how we tend to anthropomorphise these creatures. We are inclined to see them through a human lens.

The nook with writings about encounters with racoons

Crafts station

Indeed, the phrase ‘gone wild’ suggests a human-based view of wildlife as that which is uncontrolled, or uncontrollable. This idea reflects the biblical notion of nature as under our dominion. In this regard, nothing in our natural environment has escaped our influence. Those animals and plants that have survived have done so despite us. Nevertheless, the curators encourage the visitor to treat wildlife on its own terms. In one poster they write: ‘The phrase “all our relations” reflects the indigenous worldviews that understand plants and animals as “generous relatives” – family members who participate in reciprocal relations with people, and who are worthy of respect’. I take this to be aspirational, a suggestion about how we ought to treat wildlife. It certainly doesn’t reflect the predominant attitude, as evidenced throughout the exhibition.

Installation view of Toronto Gone Wild

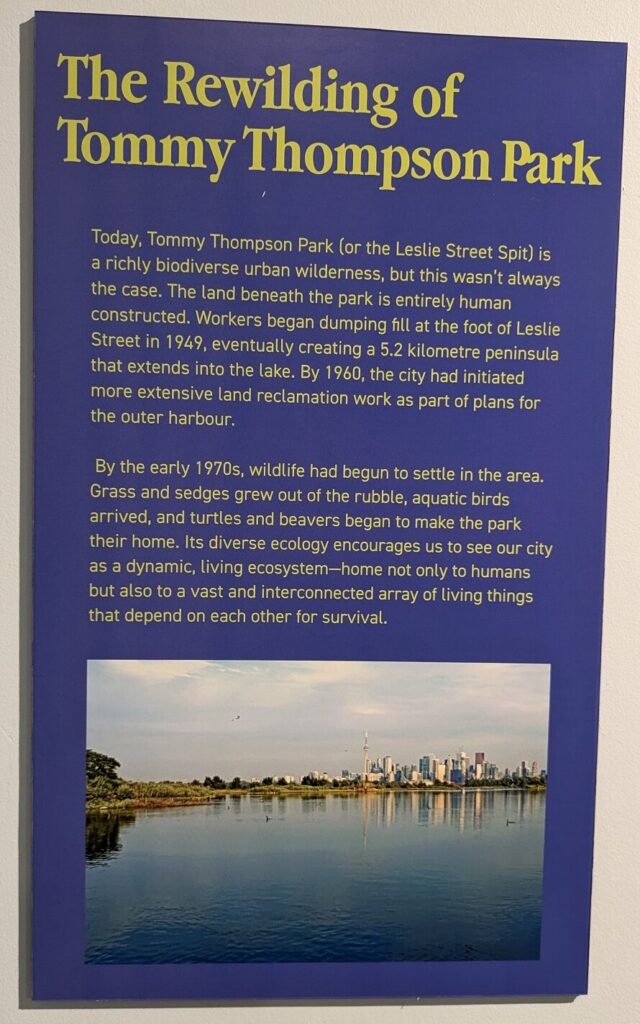

The exhibition points out how we have accidentally created new environments for wildlife – in particular the construction of the Leslie Street Spit as a dumpsite for construction waste. Nature lovers and scientists have been keen to rewild such areas, that is, more precisely, to reintroduce endangered or near-extinct species of plants and animals.

The Rewilding of Tommy Thompson Park

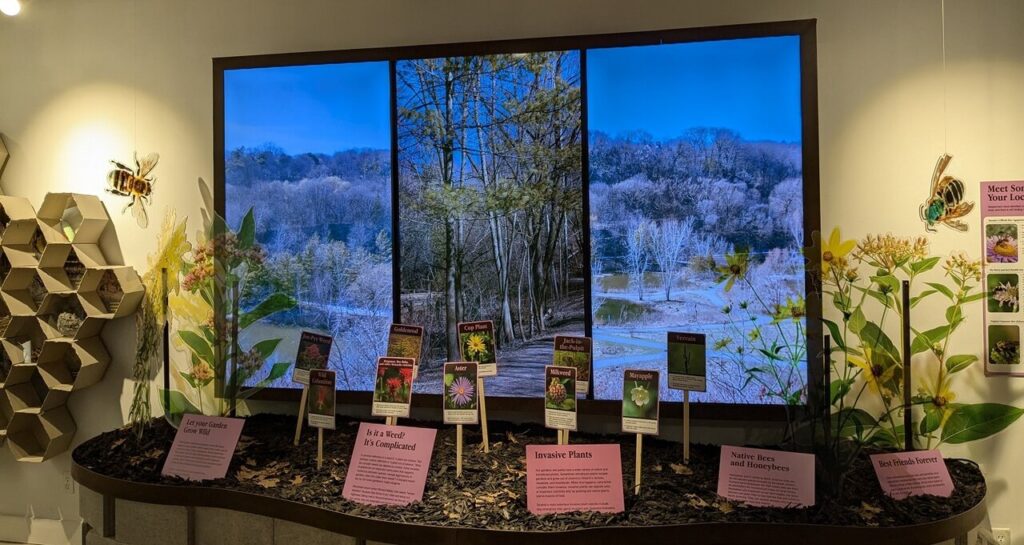

The battle between native and introduced, or invasive, species of plants and animals are brought into focus. These forces, the curators emphasize, are out of balance. But it is not clear what to label a ‘weed’ plant in this respect. Some weeds are ‘out of control’ invasive species, while others, they remind us, are native plants that perhaps gardeners are not fond of.

Installation view of Toronto Gone Wild

Superficially, the exhibition could be described as a eulogy to the wildlife immediately surrounding us. But, on a deeper reading the visitor soon realizes that things are far more complicated. It becomes clear that many of our influences on nature generally has been pernicious, if not downright toxic. This well-curated and enlightening exhibition is well worth visiting. It is a chance to consider all those living things that are peripheral to our human sphere of interests.

Text and photo: Hugh Alcock

*Exhibition information: Toronto Gone Wild, April 10 – November 3, 2024, Museum of Toronto, 401 Richmond Street west, Eastern Entrance, Ll01, Toronto. Museum hours: Wed – Sat 12 – 6 pm.