Alanis Obomsawin: The Children Have to Hear Another Story – Not just a story

Imagine this: A small girl, the only one of Indigenous blood in a grade room class, being taught lies about her Abenaki heritage. It’s the mid-1930s, and the residential school system ranges across Canada with a single goal: destroy the Indigenous cultures, languages and beliefs and replace them with those of Christian values. Imagine that little girl witnessing the collective rights of her community members being removed. Her people being denied the right to vote, sing, dance, tell stories or marry whom they loved. Imagine the stories that little girl would have been told to replace those of her ancestors.

Alanis Obomsawin (born August 31st 1932) is a documentary filmmaker, singer, artist and storyteller who has, since her own youth, strived to educate to correct the social, epistemic and ontological assumptions made against the Indigenous communities across Canada and the United States. Obomsawin means “pathfinder” and she is a member of the Abenaki tribe and lived on the Odanak reserve (near Sorel, Quebec) from the time she was six months to five years old. Some time later her family moved to Trois-Rivière, where she remained until her early 20s. The death of her father during this time pushed Obomsawin to pursue a career in education and caused her to rebel against the colonial teachings of her classes. Obomsawin’s works focus on ensuring that children, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, hear the other side to the colonial narratives so often told in Canadian and American history. In an effort to spread these messages she chose to visit local Scout troops, telling them stories, eventually touring classrooms. By the early 1960s, Obomsawin began appearing occasionally on CBC/Radio-Canada television programs, speaking to Indigenous issues, and singing traditional songs for a wide-viewing public. She made it her goal to spread the knowledge she retained from her heritage and from then on, produced and directed films, participated in interviews and collected artifacts from the children of Indigenous communities.

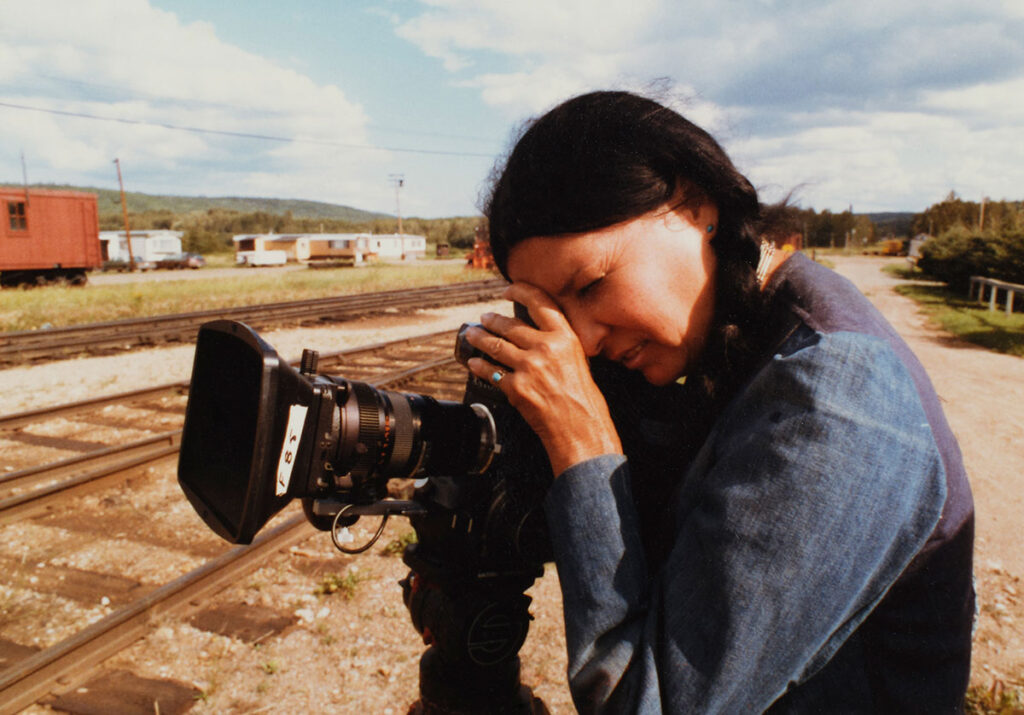

Alanis Obomsawin filming Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child, 1986. Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada and the artist.

It is this life story and goal that has evolved into Obomsawin’s current exhibition, The Children Have to Hear Another Story, at the Art Museum on the University of Toronto campus until November 25th, 2023. Upon entering the exhibit, voices fill the air from black & white as well as color televisions and projectors that are on in various rooms, enveloping viewers. A person behind the front desk offers personal headphones so you can listen to the individual stories being told as you walk between several dimly lit rooms.

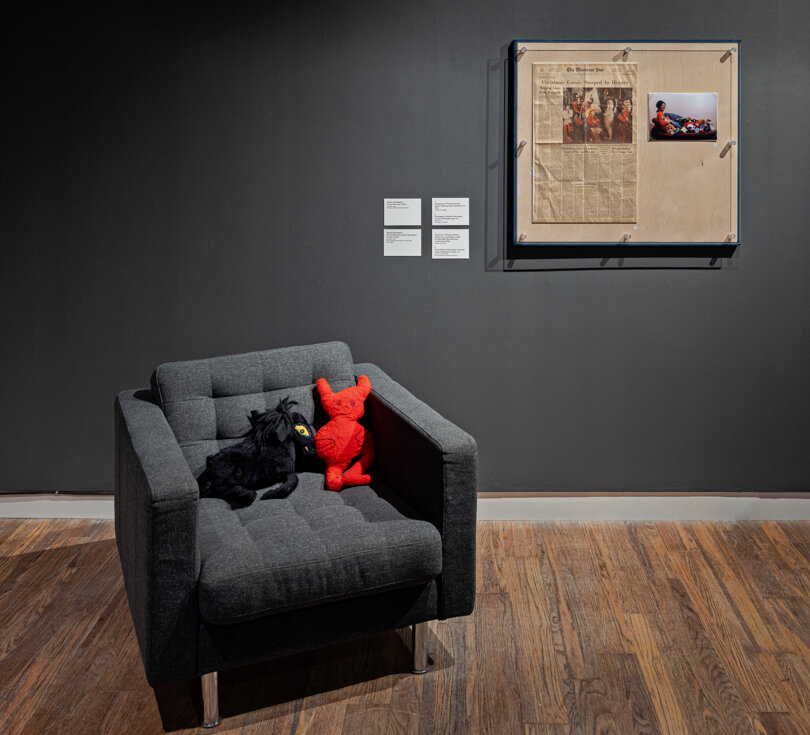

Among the video works however, off to the right of the entrance on a single couch, are two handmade animal stuffies. When Obomsawin was sixteen years old, she reflected on her childhood hardships and bullying by striving to aid in similar experiences of the Indigenous youth of the Abenaki tribe. In doing so, she taught herself to sew and from the collected drawings of local children, became inspired to create handmade dolls out of polyester and nylon. Following that year, each Christmas and Easter, Obomsawin returns to the community and hands out dolls to each child, initiating a tradition of gift giving and bringing about a sense of solidarity and connectedness among the Indigenous youth.

Installation view with handmade toys, The Children Have to Hear Another Story: Alanis Obomsawin, Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In the first of the adjoining rooms, a series of drawings can be found arrayed along the far wall. Two films, one projected to the left and one to the right, depict the visual stories of these drawings. Across from the drawings, film stills are also shared. The drawings were made by children of the Cree community of Moose Factory in northeastern Ontario. It was around Christmas time in 1971 that the drawings and the accompanying film titled, “Christmas at Moose Factory” were documented. All of the documentation provides a rich and unique perspective on the children of this community, including their family life but also the experiences of residential school students and those who attended the local village schools. They are representations of previously untold versions of Moose Factory history, as told by the children who lived there. Meanwhile, the film stills act as a record of Obomsawin’s relationship to these children. After having established a relationship of listening and playing, she encouraged the sharing of their perspectives and ideas through art. This gave the children a space to express themselves in their environments, an opportunity that Obomsawin was never given in her youth.

Installation view with Christmas at Moose Factory, children’s drawings, The Children Have to Hear Another Story: Alanis Obomsawin, Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

Obomsawin’s first full-length documentary film in 1977 was titled, “Mother of Many Children” and was shot in Burns Lake, British Columbia. The perspective of this film shifted focus to Indigenous women in various communities as they shared their insights and generational experiences. The focus was on the strength of these Indigenous women from within these communities and how they acted as the upholders of Indigenous values and teachings to youth. Within the Indigenous communities, the late 1970s to 80s reflected a period of activist movements to uphold Treaty Rights formed previously with government officials. This shift was represented in several of Obomsawin’s films, including “Mother of Many Children.” It was important during this time period to bring awareness back to the rights and land ownership of the Indigenous peoples via protest and the continuation of Indigenous storytelling to younger generations. Allowing children to engage with their birthright, while also seeing the women of their communities partake, allowed them to feel they too could stand up for the preservation of their heritage.

Alanis Obomsawin, Mother of Many Children (still), 1977. 16 mm film, colour, sound, 58 mins. Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada.

During this time, Obomsawin also released a musical album with the title track “Bush Lady.” The vinyl, first recorded by CBC/Radio-Canada in 1985, is on display behind glass casings within the elongated gallery space. This track was later remastered and re-recorded by Obomsawin in 2018. The story is told by two distinctly recognizable voices, one male and one female. The young woman is Indigenous and has just moved to a large city from a reserve, only to face victimization and racism by the male voice, who refers to her as the “bush lady.” Throughout the song, the woman’s voice is heard attempting to reply to these comments and articulate an emotive response that is never heard by its intended recipient. There is a clear contrast within the film and this song: one is indicative of a sharing of cultural and political understandings between generations, the other is a one-sided conversation. The Indigenous communities are rooted in the re-telling of histories from their ancestors to engage with their culture, language, medicinal knowledge and laws, among others. Without these conversations, their experiences become lost and unrecognized, or in some cases completely ignored by those who do not wish to listen.

Installation view with Bush Lady, The Children Have to Hear Another Story: Alanis Obomsawin, Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

At the very end of the hallway, there is a three walled space with the farthest wall having been painted red and a projected film playing directly over top. The film “Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance” (1993) depicting the causes and effects of the standoff, became the primary focus of Obomsawin’s filmmaking in the 90s. The almost two-hour documentary was filmed onsite during the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance on the territory of the Mohawk people, when the Quebecois provincial police (the SQ), and later the Canadian military, attempted to forcibly remove, and then starve, the Indigenous peoples off their land. This took place over the course of seventy-eight days, between July 11th and September 26, 1990 following the SQ attacking the Indigenous peoples with grenades and tear gas before retreating. Obomsawin remained onsite during the entirety of the standoff, documenting the long mistreatment of the Mohawk peoples on their land. She interviewed and attempted to engage with both sides of the conflict, collecting the facts behind the seemingly sudden outbursts of military force. The reason behind this confrontation was that the Quebecois government wanted to build a golf course on the territory of the Mohawk peoples, but the community refused to vacate their land. The events reached national coverage and many Indigenous tribes stood in solidarity and protested against the mistreatment of their peoples. Unfortunately, it also resulted in the emergence of various other conflicts, ones of hate and powerful backlash which led to extreme hostility against neighbouring tribes by non-Indigenous settlers. This film, and all the coverage taken during the seventy-eight days broke the national illusion that the Indigenous populations were being treated in fairness by governments and law enforcement. It told the story behind the struggles on the reserves, the torment of the Indigenous populations, opening the eyes of hundreds of thousands of people.

Installation views with Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, 1993. 16 mm, colour, sound, 119 min. Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada. The Children Have to Hear Another Story: Alanis Obomsawin, Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In an extreme contrast, Obomsawin provides an exhibition that reveals the perspectives and stories, both from that of the Indigenous and the non-Indigenous settlers, she encountered. This exhibition not only marks her continued reflection on her own mistreatment in her youth, but that of all Indigenous children who needed the space to be heard and to hear their stories being told. It also showcases how generations pass on the traditions of their ancestors to ensure their continued preservation among the younger generations that follow. Finally, it responds and re-tells the story of the struggles the Indigenous communities have in telling their stories, as they are constantly trying to re-establish non-colonial versions of their heritage.

This exhibition is about more than a young girl with a story to tell. It’s about the stories themselves and the communities those stories represent.

Lex Barrie

Images are courtesy of the Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

*Exhibition information: The Children Have to Hear Another Story by Alanis Obomsawin, September 7 – November 25, 2023, Art Museum at the University of Toronto, University of Toronto Art Centre, 15 King’s College Circle, Toronto. Museum hours: Tue – Sat 12 – 5 pm, Wed 12 – 8 pm.