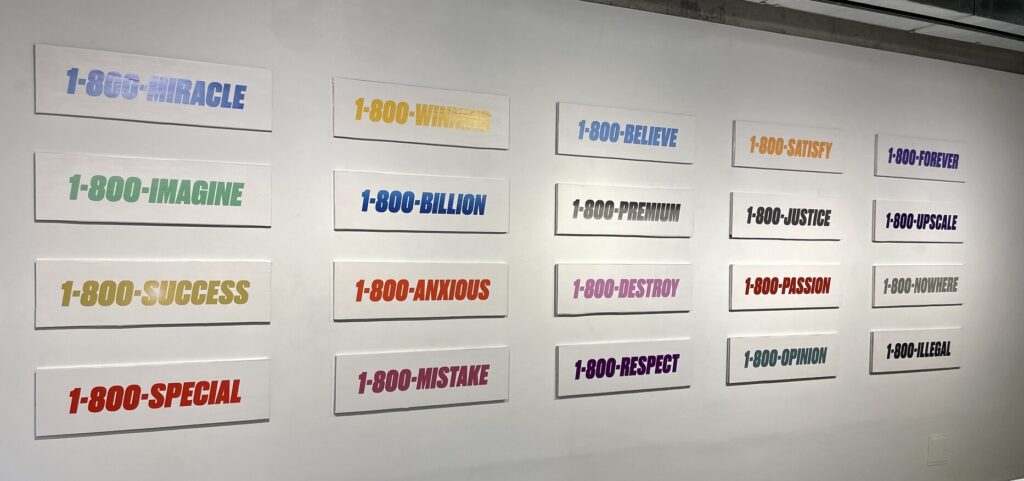

As the Propeller Art Gallery itself proclaims, it is hosting a show unlike any in its history. The show, titled Much Too Much, features the text-based conceptual art of Stefan Wegner, an artist with a background in advertising. The well-lit gallery space is crammed with artworks – nineteen in all. Its sheer scale in such a modest space is betrayed by the length of time the viewer must spend there in order to appreciate all on display. In particular there is a cornucopia of text. Too much, as the show’s title perhaps suggests.

Installation view of Stefan Wegner, Much Too Much at the Propeller Art Gallery

It is indeed exciting that a gallery that usually shows traditional aesthetically based artworks – as a rule, either paintings or sculptures on pedestals – has chosen to highlight conceptual art. It is refreshing. Their claim, however, that this show is ‘absolutely unique in the current art world landscape’ is simply not true. Let’s put it down to promotional hyperbole. Wegner’s work fits in the mainstream of conceptual art, and loosely echoes the work of such luminaries as Canada’s Ian Carr Harris, and text artists Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer, to name but a few.

Installation view of Stefan Wegner, Much Too Much at the Propeller Art Gallery

In his artfully designed catalogue Wegner explains: ‘I work with words. When thoughtfully arranged and applied to objects that amplify or deepen their meanings, words will surface values…’. This kernel of an idea is illustrated, for example, by his piece Revisionism of Man/Woman. Here we are presented with anonymous portrait paintings (or facsimiles thereof) of a middle-aged man and woman respectively. Near the bottom corner of each is placed a small digital screen – the actual artwork in this case – that displays a changing set of titles for each, e.g., ‘Unregistered Massage Therapist’ for the man, and ‘Too Many Piles Again’ for the woman. Each passing title, Wegner suggests, changes any portrait you might place next to it. One portrait becomes one hundred. Such is the magical power of words one supposes.

Stefan Wegner, Revisionism of Man/Woman.

This strategy is an old one. For example, back in 1884 Frenchman Alfonse Allais exhibited a series of monochrome paintings with titles written on their frames. A red expanse, for instance, is given the title that translates as ‘the harvesting of tomatoes by apoplectic cardinals by the red sea’. Likewise, humour is the signature basis of most of Wegner’s works.

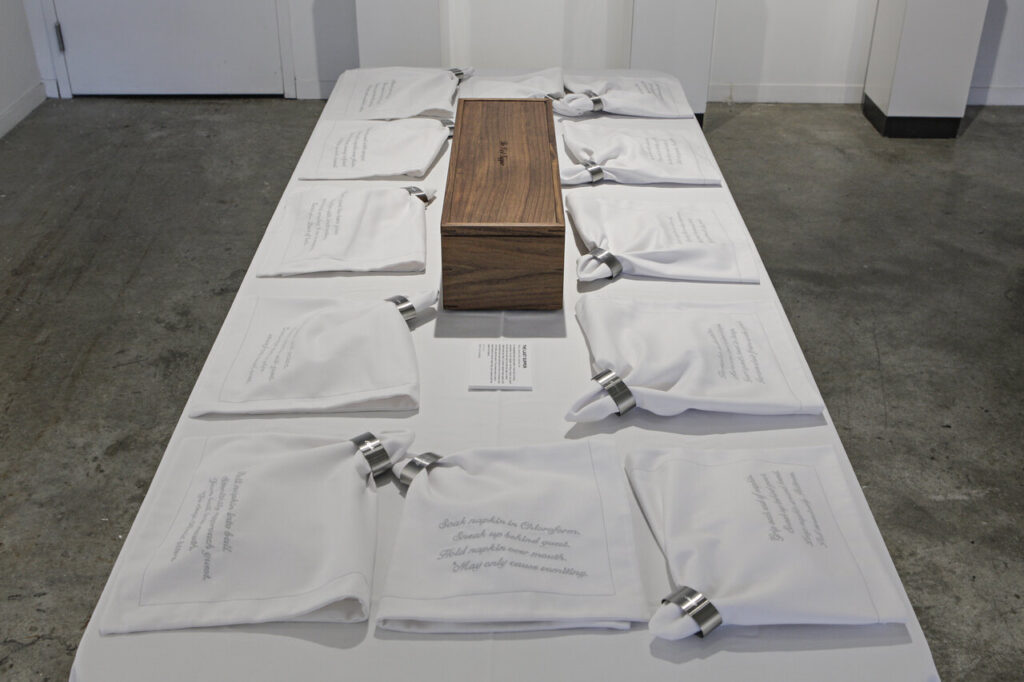

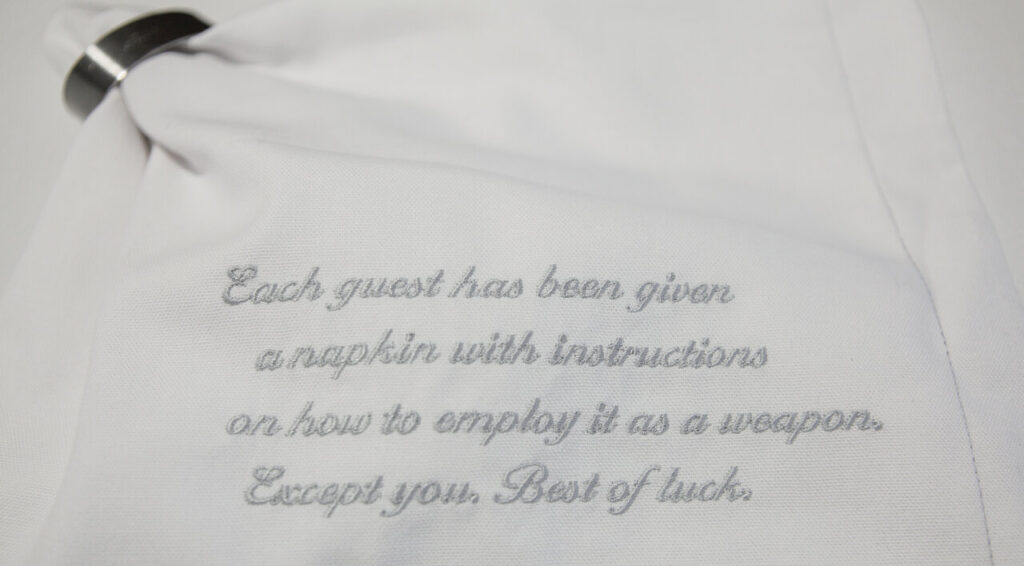

Stefan Wegner, The Last Supper, installation (above) and napkin (detail, below)

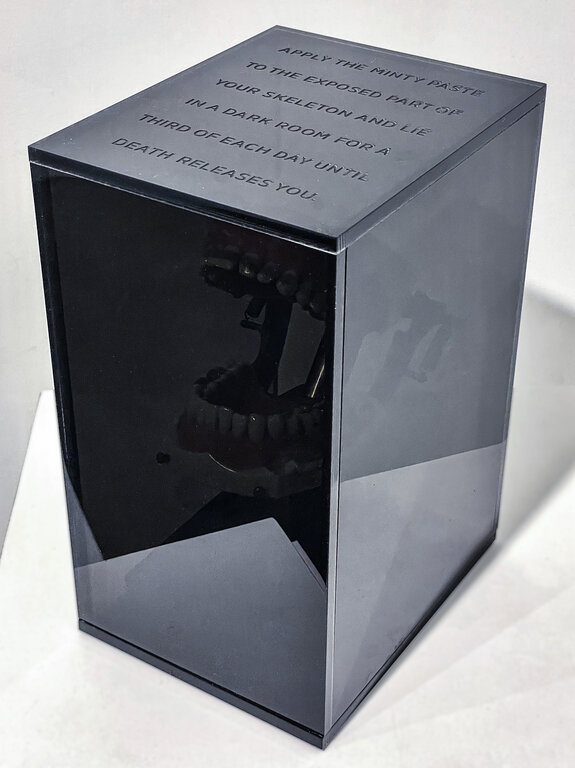

At times his humour is deliciously dark. For example, he titles one piece The Last Supper. It consists of a box together with a set of a dozen fancy napkins, on each of which is stitched instructions on how to use the napkin to end a diner’s life, e.g., to strangle her. Or again, in the case of Stolen From a Meme, Wegner offers up a dark semi-opaque box which, the viewer can vaguely make out, contains a set of teeth. On the box is inscribed: ‘Apply the minty paste to the exposed part of the skeleton and lie in a dark room for a third of each day until death releases you’. All told most of the works are entertaining in this way. As well, they are all flawlessly crafted.

Stefan Wegner, Stolen From a Meme

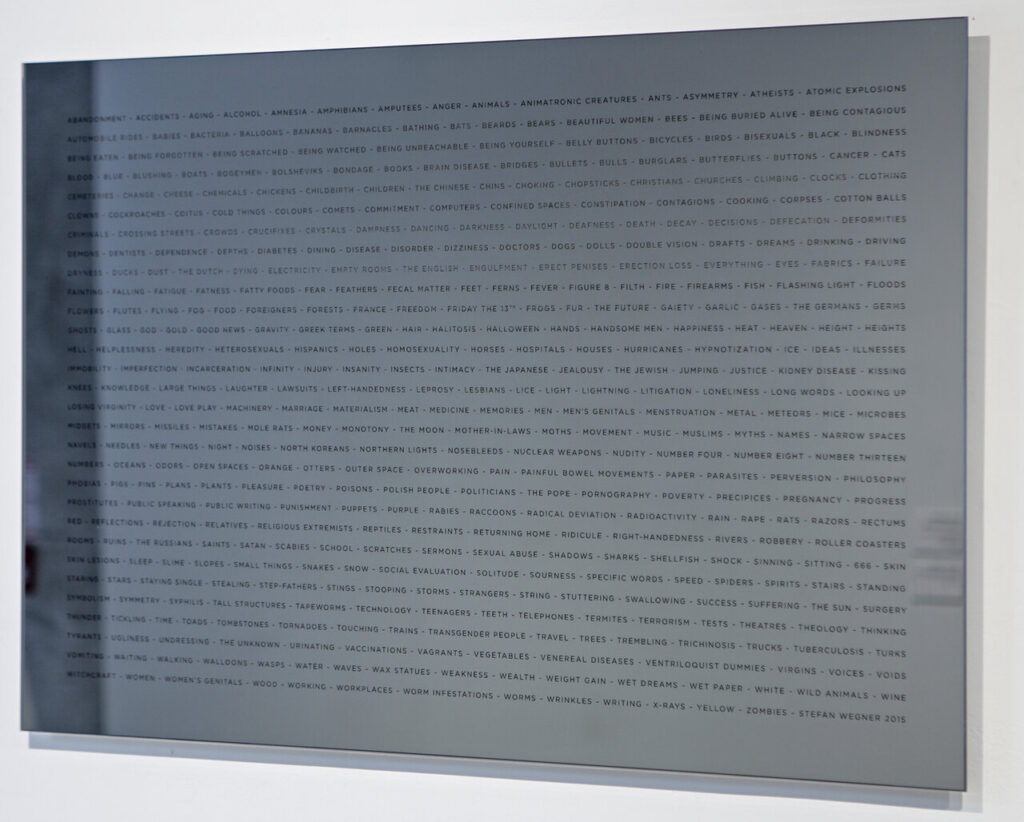

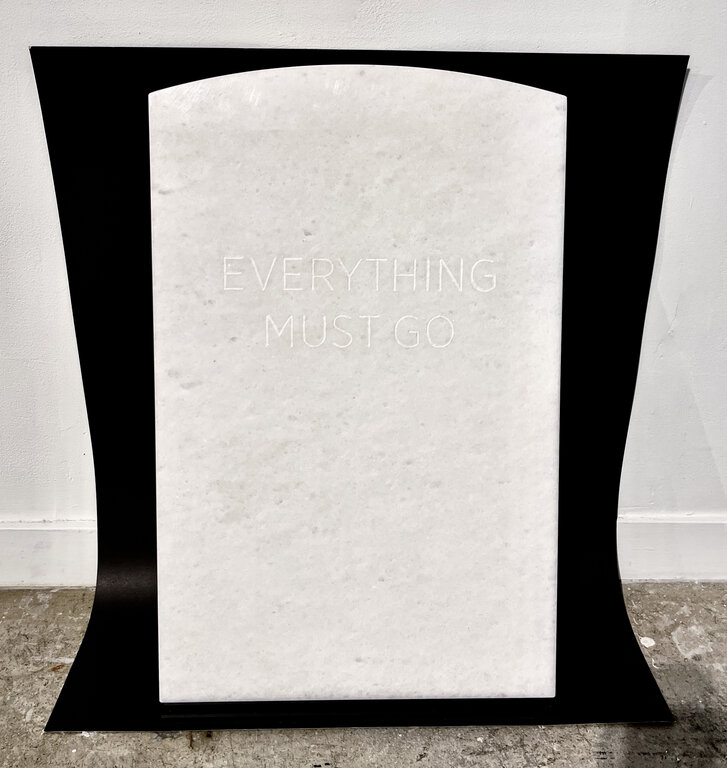

Very often Wegner’s use of words is to compile lists. His Spectrophobia, for instance, comprises a mirror etched with hundreds of words that name, according to Wegner, common phobias such as fear of God, telephones, darkness and daylight – we fear almost everything it seems. In general, he has the urge to hold back very little, tending towards what one might call a verbal horror vacui. In this vein, every work is also accompanied by an explanation. It is not clear this helps. Take the case of his Everything Must Go, which consists of these very words carved into a tombstone shaped piece of white marble. There is little need to explain to the viewer what it is trying to say, as he does. It is best to give space to the viewer to interpret the work for herself, I feel. It is is this lack of poetical space in this sense that diminishes the impact of the work.

Stefan Wegner, Spectrophobia

Stefan Wegner, Everything Must Go

By ‘poetical’ I mean the non-literal. The space I speak of, therefore, is the semantic gap between words used in a literal sense and their use poetically, or metaphorically most often. It requires the effort of the viewer to bridge this gap. Text based conceptual artists such as Barbara Kruger and Robert Montgomery, are aware of this poetical dimension to their work. And this is reflected in their being influenced by poetry itself.

In his introduction Wegner explains that he ‘works tirelessly to uncover thoughts, feelings and values that are worth exploring’. I take it though that it is the process of their uncovering that matters, not the ideas in themselves. That is to say, insofar as conceptual art is art at all, and not merely the illustration of some idea or other, it is when the artwork’s meaning is essentially linked to how it is expressed. Accordingly, words, as the medium of communication here, ought not to support or amplify an idea, as Wegner claims, but rather the idea ought to inhere in the way the words are used and their concrete expression in the artwork.

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of the artist.

*Exhibition information: Stefan Wegner, Much Too Much, July 12 – 30, 2023, The Propeller Gallery, 30 Abell St, Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed – Sun, 1 – 5:30pm.