As part of the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, the Stephen Bulger Gallery is showcasing recent works by Sarah Anne Johnson, in a show titled Woodland. Johnson produces photographic works with a lyric twist. That’s to say, she manipulates the bare photographic image to infuse it with feeling, or as she puts it, by depicting ‘not just what I saw, but how I feel about what I saw.’

Installation view of Sarah Anne Johnson, Woodland with (L to R:) ACITR, PTODG and CPIP3

Johnson’s primary vehicle for her lyricism is colour. In these works we are confronted by images of Manitoba woodlands in full sunshine, which is emphasised by her use of highly saturated colours. As well, she has added painted shapes using various materials including oils and photo-spotting ink. Some, e.g., her piece titled PITFD2, are reminiscent of the early fauvist paintings of Henri Matisse. I have in mind, in particular, his Luxe, Calme et Volupté (1904), with its mixture of strident colours and a coarse form of pointillism, that depicts nude bathers on a beach. Fauvism, a movement at the very beginning of the twentieth century, is defined by its artists’ brash use of colour and decorative form.

PITFD2, 2020, Unique Pigment print with hand-applied photo-spotting ink mounted to Stonehenge on Aluminum Composite Panel, 40 x 60 inch

Johnson’s techniques and preoccupations are in the main quite different from those of the fauvists. Nonetheless, there is a parallel here. Fauvist André Derain, for instance, said that ‘colours became charges of dynamite. They were supposed to discharge light.’ (Concepts of Modern Art, London: Thames and Hudson, p. 26). This idea – central to fauvism – that colour can transcend mere pigment, is echoed in Johnson’s own work. In her series titled, Arctic Wonderland (2011), for example, she altered photographs of various scenes taken on a trip to the arctic by crudely painting fireworks in the sky using photo-spotting ink. She remarks that she used the colours, ironically, to point to the natural beauty of the desolate arctic landscape itself. The following year she produced a series featuring overhead sculptures based, again, on fireworks. These sculptures included various coloured lights.

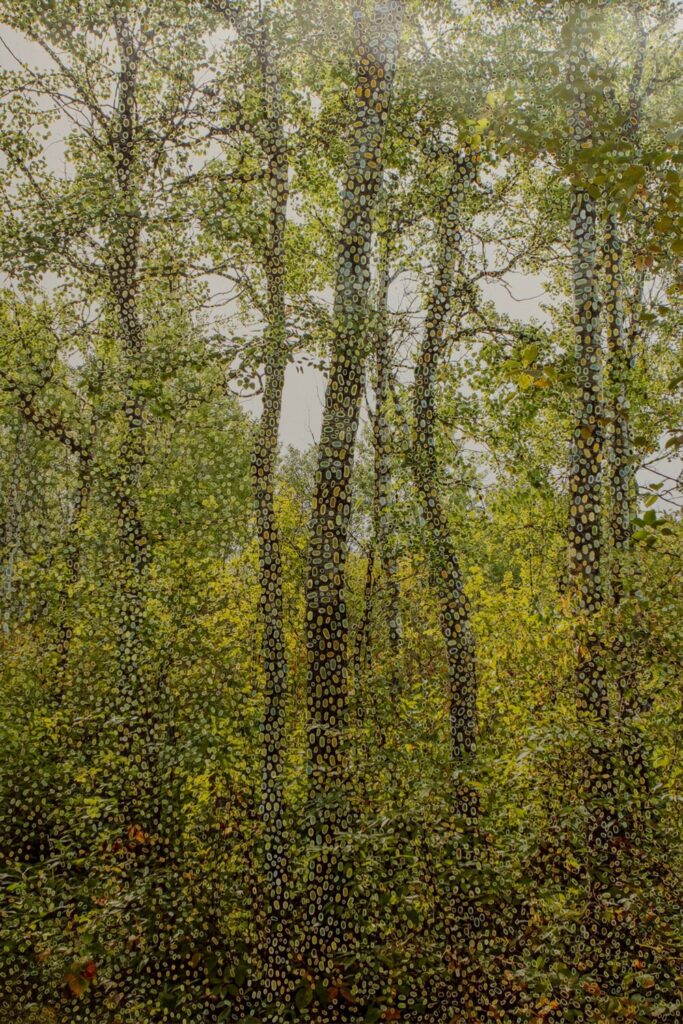

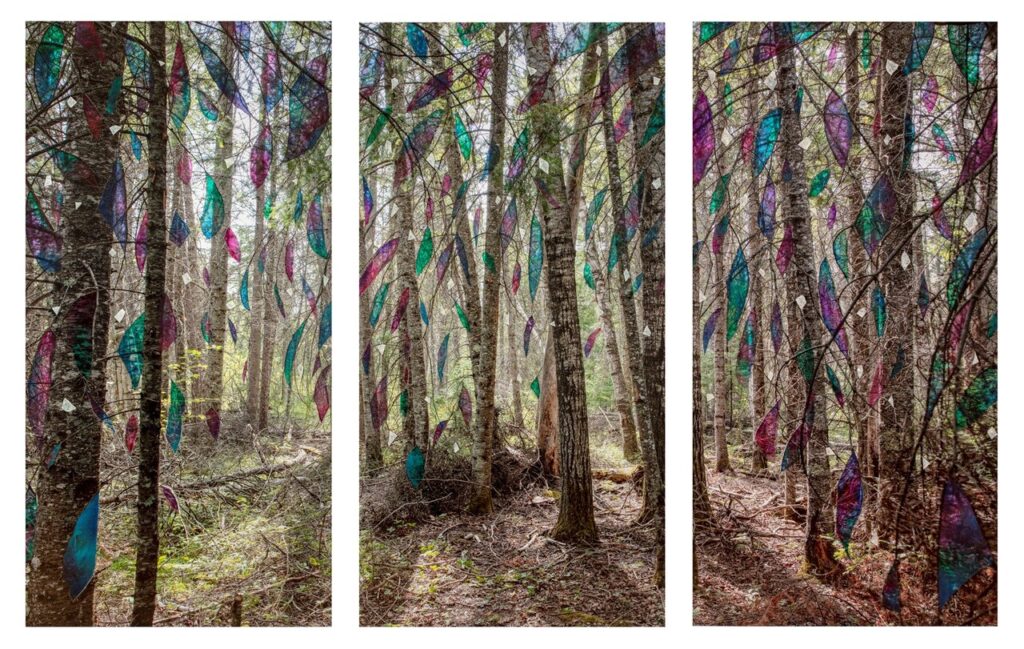

In this show most of the eleven works feature photographs of the woods with numerous translucent shapes, either floating, bubble-like, in the foreground or woven between the angular interstices of the branches. The effect is similar to that of stained glass windows, which gives some of the pictures a religious connotation by mere association. But surprisingly, for me two of the pictures that stand out in the show (PTODG and PTMW, as she strangely titles them) sparingly use only earthy greys in the interstices. These understated images sing in a quiet way.

PTMW, 2020, Unique Pigment print with hand-applied oil paint mounted to Stonehenge on Aluminum Composite Panel

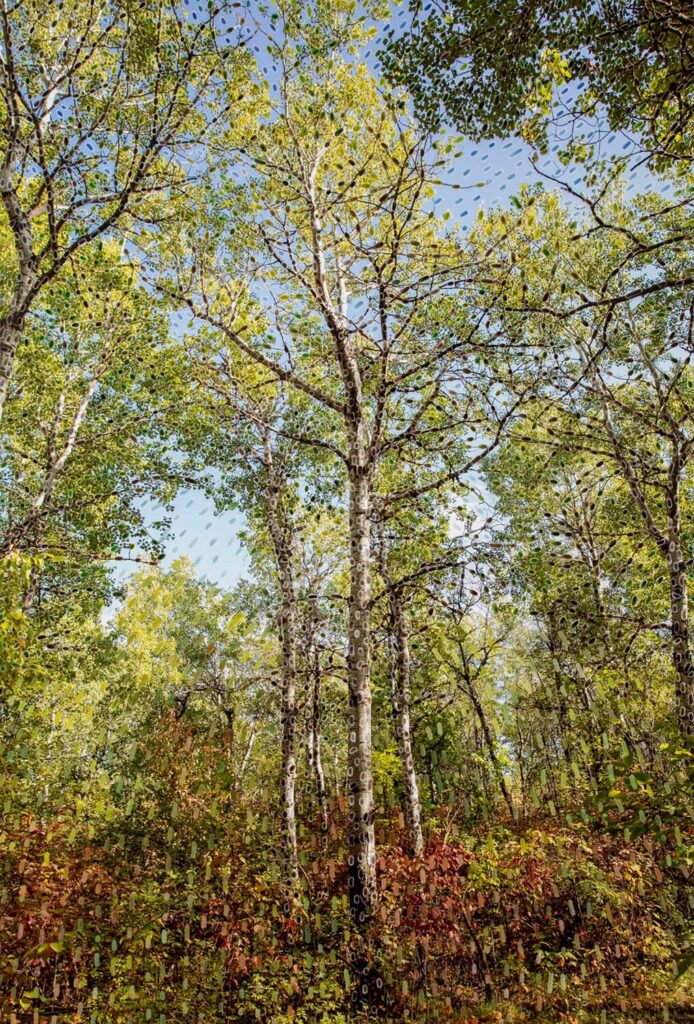

Perhaps the most haunting image of all, PTST consists of a relatively muted photograph of a stand of about half a dozen trees on top of which Johnson has added hundred of light-coloured dots of photo-spotting ink. The pointillist effect is so pronounced that the image resembles a strange infestation of insects. This effect is, again, quite beautiful. It is these quieter pieces that, to my mind, are most successful in terms of lyricism – less pizazz than their more colourful counterparts, but more soulful.

PTST, 2021, Pigment print on archival paper with photo-spotting ink mounted to Stonehenge on Aluminum Composite Panel

As already noted, Johnson’s photographs were taken in full sunshine, creating the appearance of their being backlit. It is this fact that makes the coloured patterns painted on the surface resemble those of stained glass. And this again echoes the fauvism of Matisse especially, who designed several well known stained glass windows. This is an interesting medium insofar as it lies somewhere between craft and ‘fine’ art, to use a rather dated term. Many contemporary stained glass windows fall under the category of craft in virtue of being purely decoration. But, as many stained glass windows featured in cathedrals and churches attest, the medium can be used not merely to please the eye, but also didactically, namely, to illustrate biblical stories in a dramatic fashion. And I think this tension between art and craft, vis-à-vis the decorative, is found in Johnson’s pictures.

MBFR, 2021, Set of three Pigment prints on archival paper with oil paint, each mounted to Stonehenge on Aluminum Composite Panel, each 69 ¾ x 34 ⅞ inch

The didacticism of these pictures is not immediately detectable. But they are clearly designed to project a certain aura, to emanate a feeling of a sort. And this feeling, I assume, relates to her own comment that her work ‘is informed by scientific research on the ability of trees to communicate intelligently, traditional indigenous knowledge about nature and the influence of ancient trees on sacred architecture.’ She wants to relate a reverance for trees, to intimate their interconnectedness to one another, and to us perhaps.

CPIP3, 2021, Pigment print on archival paper with acrylic paint mounted to Stonehenge on Aluminum Composite Panel, 40 x 60 inc

Her use of coloured patches borders on the decorative, to the extent that at times it is hard to experience anything other than the sensual delight the images produce. It seems as if we are looking at a land of dappled sunshine and butterflies. But more often she transcends such hedonism, to produce pictures with a magical atmosphere that hints at the sacred architecture she speaks of. There is a fine balance between art and craft in this sense, given that the decorative can play a vital aesthetic role – a way of elevating art, as Matisse once suggested – that Johnson, in the end, succeeds in doing.

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery.

*Exhibition information: Sarah Anne Johnson, Woodland, May 1 – June 24, 2023. Stephen Bulger Gallery, 1356 Dundas St. W., Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat 11am – 6pm.