Visitors of the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto are forced to ponder the age-old existential question: what will happen after we die? Tumbling in Harness abandons the corporeality of death and turns towards the digital self: what will happen to our Instagram accounts after we die? Curated by Erin Reznick, this show exhibits works by international artists that delve into the topic of online death and digital memorialization. The temporality of the physical self is confronted with the seemingly immortal online presence. The capitalistic nature of social media’s algorithms and controlled distribution is emphasized by online death, making space for the commodification of death services like the distribution of personalized messages from deceased loved ones.

Installation view of Tumbling in Harness

Upon entering the exhibition, the visitor is confronted with two unapologetic, black body bags, lying next to each other on the light wooden floor. Untitled (The traffic noise arched over a bubbling mass of public conversation and pattering footsteps on concrete) (2021) by Vunkwan Tam is a visual simplification of the concept of death, referring to our society’s desensitization towards death. The event is made marketable on social media, a victim to the algorithms that control and govern the online social world and resulting in unfathomable corporeality, or “digital disembodiment”. The palpable death of the physical being, as represented by the work of Tam, is juxtaposed with Suspended Vision (2019) by Stine Deja, a video work placed above the body bags of Tam. A video of an upside-down human face blinking literally exemplifies the suspension and disassociation of the self (and digital presence) from the physical body. As if the digital soul is literally removed from the physical body and suspended above, in a digital medium, Suspended Vision continues the story told by Tam’s body bags. This video work also introduces the commodification of immortality and preservation services, such as cryogenic freezing. Death and grief’s adoption into an economic system tie in issues around access and privilege, where only the wealthy can afford to have their bodies cryogenically frozen. Symptomatic of the human desire to preserve life and strive for immortality, Suspended Vision presents the option of being ‘frozen’ in the digital world.

Installation view with Stine Deja, Suspended Vision, 2019, video, Vunkwan Tam, Untitled (The traffic noise arched over a bubbling mass of public conversation and pattering footsteps on concrete, 2021, body bags

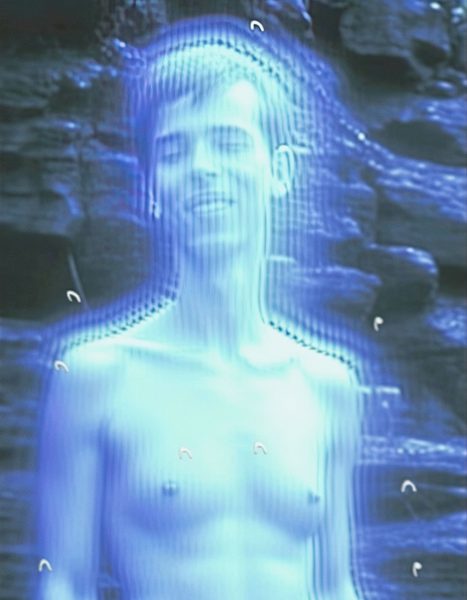

Adjacent to the two works hang Charlie Engman’s photographic interventions. Using a digital software to transform prompts into a visual death-vocabulary of sorts, Engman transforms the concept of digital death into a consumable photograph. Resulting in a visual representation of the separation of the spirit and the body, he captures the spirit of the deceased in an eerie image. The photographs incorporate glowing hazes of light, bodies morphing into a digitized abstracted representation. This transience is scattered with imagery of white avian parts such as feathers and wings, bringing in a heavenly sense to the ghostly photographs as seen in Owl Gate (2023).

Charlie Engman, Halo, 2023. AI-generated image on archival foam

The next room is dedicated to Russell Perkins’ sound work, The Future Tense (2021). A conceptual auditory experience, it plays an AI-intervened version of Johannes Ockeghem’s Requiem from 1460, a polyphonic mass commonly associated with religious, funerary practices. Using an AI software, Perkins incorporates “mobility insights” from data tracking movements of populations during the pandemic. Most impactful in this sound work is the extended rest, a period of no sound, referencing the lack of data and movement. The visitors are invited to seat themselves on muted blue chairs, taking the appearance of benches found at airport gates. The clinical, empty walls and off-white colour of speakers interact with the airport chairs to create a space of transience and unsettlement, referencing the in-between state of the digital presence of a deceased person.

Russell Perkins, The Future Tense, 2021, sound work, speakers, airport chairs

The next two works are located in a room whose walls are draped with thick, forest green curtains. As the viewer steps in, the coldness of the previous room is juxtaposed with this lush, intimate parlour, an installation by Common Accounts, a duo composed of Igor Bragado and Miles Gertler. You’re Well Liked in Your Community (2023), a multi-media installation features two plastic jugs of alkaline hydrolysis fluid remains, placed on a rolling platform and illuminated by a spotlight. In the top right corner hangs a red LED sign from the ceiling with text taken from YouTube comments and “death-care industry slogans” scrolling across the screen. Common Accounts is investigating the digitization of memorialization through virtual afterlives and caring for one’s digital presence post-death. Essentially, one’s presence exists on in the cloud, making it a quasi-digital heaven, or afterlife. The plastic jugs reintroduce the body, the physical, to this digital death concept and present an alternative to body disposal services, emphasizing the transference of oneself from their physical state to a digital one. The LED sign brings in notions of memorialization and the digital space as a site of information, and data, a continuation or prolongation of digital life activated by mourners.

Common Accounts (Igor Bragado and Miles Gertler), You’re Well Liked in Your Community, 2023. Multi-media installation, alkaline hydrolysis fluid remains, heavy duty polyethylene, curtains, single-colour LED sign.

The conclusion of the exhibition is a video by Oreet Ashery, Revisiting Genesis – Episode 8: Bambi, Death Online (2016). The notion of memorialization is continued in this web-series documentary of the management of the digital self after death. Ashery presents services that capitalize on the distribution of messages from a deceased person’s digital self. This commodification of memory exemplifies our society’s progression to a world where the self does not stop with the physical, rather transcends corporeality and exists digitally, therefore companies must capitalize that realm of existence as well.

Tumbling in Harness successfully confronts online death through its diverse works that engage with the digital at the same time as critiquing the progression of our society. This exhibition answers the question “what happens when we die” and presents new avenues to explore surrounding death, such as digital memorialization, anti-corporeality, and capitalistic control over death. This exhibition leaves a lasting impression promoting the contemplation of the intersection of (im)mortality and the digital realm.

Nina Ankisetty

All images Installation view: Tumbling in Harness / Group exhibition, May 3–July 22, 2023, Art Museum at the University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy of the Art Museum at the University of Toronto.

*Exhibition information: Tumbling in Harness, May 3 – July 22, 2023, Art Museum at the University of Toronto, Justina M. Barnicke Gallery (in Hart House) 7 Hart House Circle, Toronto. Museum hours: Tue, Thurs, Fri, Sat 12 – 5 pm, Wed 12 – 8 pm.