Dr. Robin DiAngelo, author of What does it mean to be White? Developing White Racial Literacy, describes how white identifying members of society are programmed to respond to racism in a state of fragility and defense, triggering emotions of anger, fear, and guilt. This recognition of internalized dominance – in which the experiences of the members of a dominant group are considered normal or accepted as superior – causes white individuals to provide evidence of their “non-racist” status which can ultimately be viewed as demeaning and proof that they are unable to face authentic differences in society. We often encounter phrases such as, “my parents taught me to treat everyone equally” and “I don’t care what colour a person is” when discussions of race or racism are brought to the table. However, these deflections are ultimately false. No matter how many times white individuals provide evidence of their non-racism, they are still privileged throughout society and history. Evidence does not mean “non-racist” and just because there might be no conscious sense of hatred towards another group or persons of color, that does not mean that a white lens isn’t in use daily.

Installation view with Deanna Bowen’s White Man’s Burden, installation of giclée prints on paper and oil on canvas (left). Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

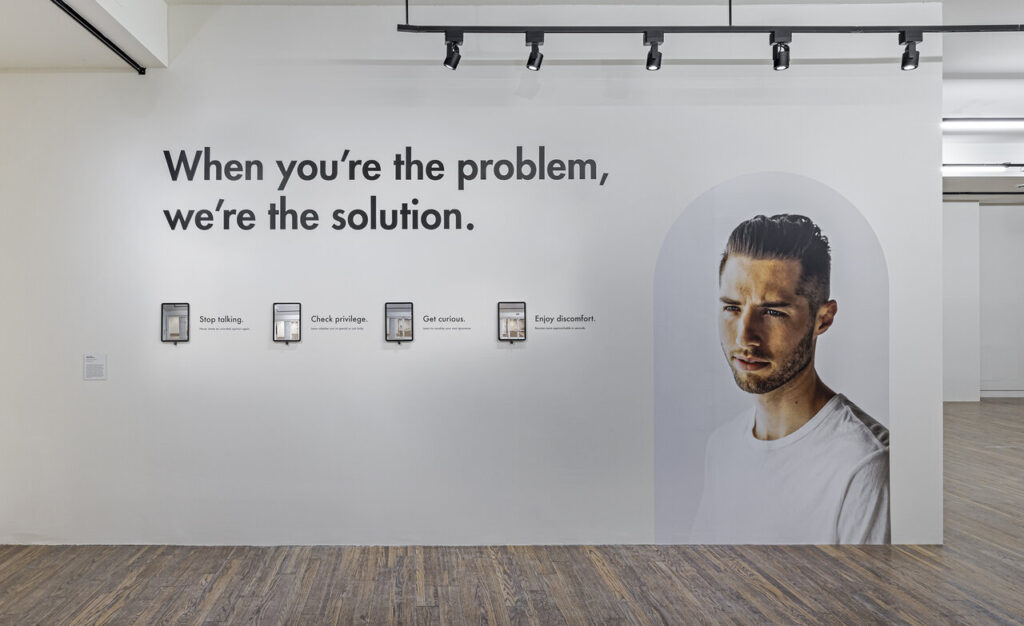

The exhibition, Conceptions of White, at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto campus, tackles these ideals by examining the meanings behind “white race” and the origin of “whiteness” in North America. Curated by John G. Hampton and Lillian O’Brien Davis, the exhibition includes the featured artists’ interpretations and understandings of the historical foundations and social constructs of white supremacy and fragility. On entering the gallery space, first we met Jeremy Bailey’s Whitesimple with a feature of four small mirrors hanging at the approximate eye level of the average person. Each mirror has a pasted text beside it to read: Stop Talking, Check Privilege, Get Curious and Enjoy Discomfort. Above the text and mirrors is a larger text reading: When you’re the problem, we’re the solution. Immediately, viewers are forced to reflect and evaluate their position prior to engaging with the artworks. In our current social context, this is where the sense of white fragility is being asked to present itself for all white individuals entering the space. It is a reminder that no amount of evidence provided can be used to derail the conversation of race about to be presented.

Installation view with Jeremy Bailey, Whitesimple, costum augmented reality filters. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

The text and mirrors then beckon audiences to the first of the artworks, Portal, by Robert Morris, which is meant to signify a shifting of perspective as one goes further into the gallery, speaking to the ideas of whiteness. Whiteness, according to the artist’s statement, “acts as a neutral background we do not see, within which everything is framed”. Contemporary art galleries themselves are actually considered “white cubes”, a term that was coined in the early 20th century. Its sole purpose was to minimize distraction outside of the artwork that was being displayed. Something as simple as a wall color can reflect the thought patterns of the majority in society.

Installation view with Robert Morris, Portal, 1964. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

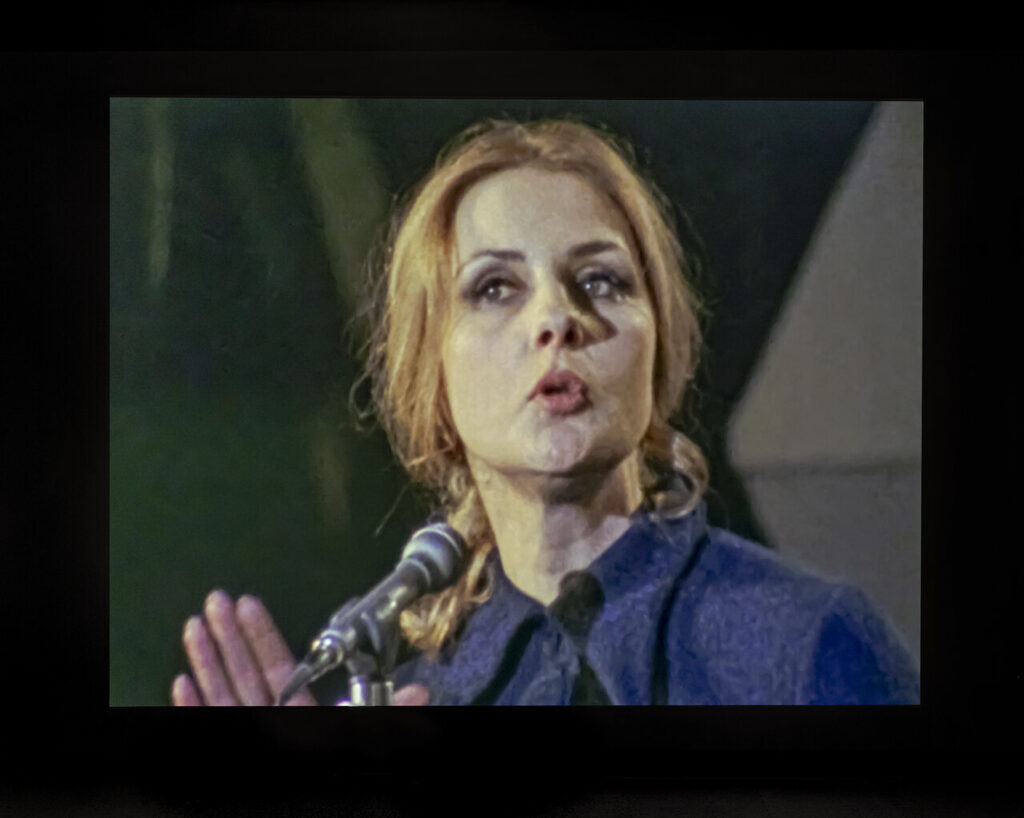

Entering the room to the left, a five-minute video is displayed. Michèle Lalonde’s Speak White is an excerpt from the film La Nuit de la poésie (1971) which was made in response to the historical use of the term “speak English” which Anglophones used in the 60s and 70s to remind French speakers of their inferiority. Despite one assuming that this exhibition would concentrate on race from the perspective of skin color, it is actually interconnected with geographical and cultural hierarchies. This artwork was included to make the point of denouncing imperialism and oppression of any individual who was forced to assimilate into the majority. French settlers on the East coast, known as the Acadians, were an established colony prior to British invasion, in which they forcibly separated children and mothers from their fathers and husbands, shipping them off to the southern American states to learn English. Racial hierarchies are about more than just skin color. They are about privilege and power.

Michelle Lalonde, Speak White, 1968. Excerpt from the film La Nuit de la poésie 27 mars 1970 by Jean-Claude Labrecque et Jean-Pierre Masse, 1971. Video, 5 minutes. Video from the collection of the National Film Board, courtesy of the Michèle Lalonde estate. Poem © Michèle Lalonde, 1968. All rights reserved in all countries and in all languages.

The exhibition’s whole is assembled from works of varying time periods, targeting the many attempts of white supremacy to eradicate or assimilate other cultural groups into their own. Hiram Powers’ Model of a Greek Slave (which in this exhibition is a 3D replica of the plaster sculpture from 1843) was brought in to reflect on the use of the term “Caucasian” through history. The sculpture is of a white Christian woman who was taken prisoner from the Caucasus region (now present-day Azerbaijan). Once Africans were abducted into the American slave trade, white slaves were almost completely eliminated. This sculpture was used in argument against the African slave trade, as it enabled white settlers of the time in America to feel empathy for a white woman in shackles (though the shackles of this 3D printed replica, were not included). One could say the removal of the shackles for this exhibition signifies the freedom of white power structures in society, freeing themselves from bondages that could hold them back.

Installation view: Hiram Power, Model of the Greek Slave (1843). Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Directly behind that sculpture is a vinyl wall installation by Ken Gonzales-Day, The Wonder Gaze. Gonzales-Day’s installation originated in a series called the Erased Lynchings which he created as a response to the popularity of lynching postcards made in the 20th century for souvenir purposes. The artist takes images from lynchings which occurred across the United States, but he removes the victims involved. His focus is to bring light to the audiences of these lynchings. His statement refers to the idea of “white herd mentality” which normalized and perpetuated these torturous, violent acts as social events. To be frank, I immediately assumed the victims were African-Americans. I have only ever seen images of black individuals being brutalized by white individuals. Though I was aware of the torture of individuals among white people, it did not immediately come to mind that these victims were two white men. The 1933 lynching of John Holmes and Thomas Thurmond were not committed because of visible racial characteristics, but because of their consideration as inferior white southern men in comparison to their northern counterparts. This was an act of classes, of which the higher assumed a position of superiority attempting to remove those who they deemed inferior to exist in the same space as they do.

Ken Gonzales-Day, The Wonder Gaze (St. James Park, CA. 1935), 2006–2022, Erased Lynchings series, print and vinyl wall installation. Courtesy of Luis De Jesus, Los Angeles.

A white lens in society is one that does not recognize its privilege as the voice of a higher-powered majority. It is more than just skin color; it is an exertion of power against those in the minority or those who are simply deemed of lower status than the majority. It is also not about providing evidence so you don’t have to hear the conversations happening around you. The exhibition provides evidence of needed action to redirect our thought patterns about race. The artworks provide various versions of stories encompassing the history of what it means to have whiteness and to use it or have it used against you in society. Thus, these are the conceptions of whiteness: power over those who don’t have it and the usage of it to build the very fabric of societies we know and live in today.

Lex Barrie

Image courtesy of the Art Museum at the University of Toronto.

*Exhibition information: Conceptions of White, a Group Exhibition, January 11 – March 25, 2023, Museum of University of Toronto Art Centre, (in University College), 15 King’s College Circle, Toronto. Museum hours: Tue, Thurs, Fri, Sat 12 – 5 pm, Wed 12 – 8 pm.