Part of the fun in seeing art up close is figuring out how it’s been made: an experience of discovery that is easily overlooked in the online world. I’ve selected just a few examples of work from the Art Toronto show that surprised me with an “oh… that’s how it works” revelation:

Three works by Kal Mansur, Myta Sayo Gallery, Toronto

Kal Mansur’s elegant pieces at Myta Sayo Gallery initially appeared to be flat geometric abstracts, but slowly revealed themselves to have a foggy depth. They’re actually three-dimensional constructions under a translucent surface. I couldn’t help but try to guess how the interiors are organized and structured.

Three works by Christian Eckart, TrépanierBaer Gallery, Calgary

Trépanier Baer Gallery mounted these round works by Christian Eckart on the outside of their booth. The faceted and fractured coloured shards glowed like stained glass windows and yet they seemed to be impossibly thin. Up close, I discovered that they were made of canvas, and directly adhered to the wall without any other framing or backing.

James Nizam, Superposition, archival inkjet print, Gallery Jones, Vancouver

Gallery Jones had a large photograph by James Nizam. At first glance, it appeared to be a photo collage combining before-and-after views of a room demolition. But on closer inspection, I saw that it was a single unmanipulated photograph. Floors and walls had been precisely and carefully cut away. The geometry of the incisions followed a meticulously calculated reverse perspective that aligned with the position of the camera. At any other location in the room, I imagine, the geometry would bend and break apart.

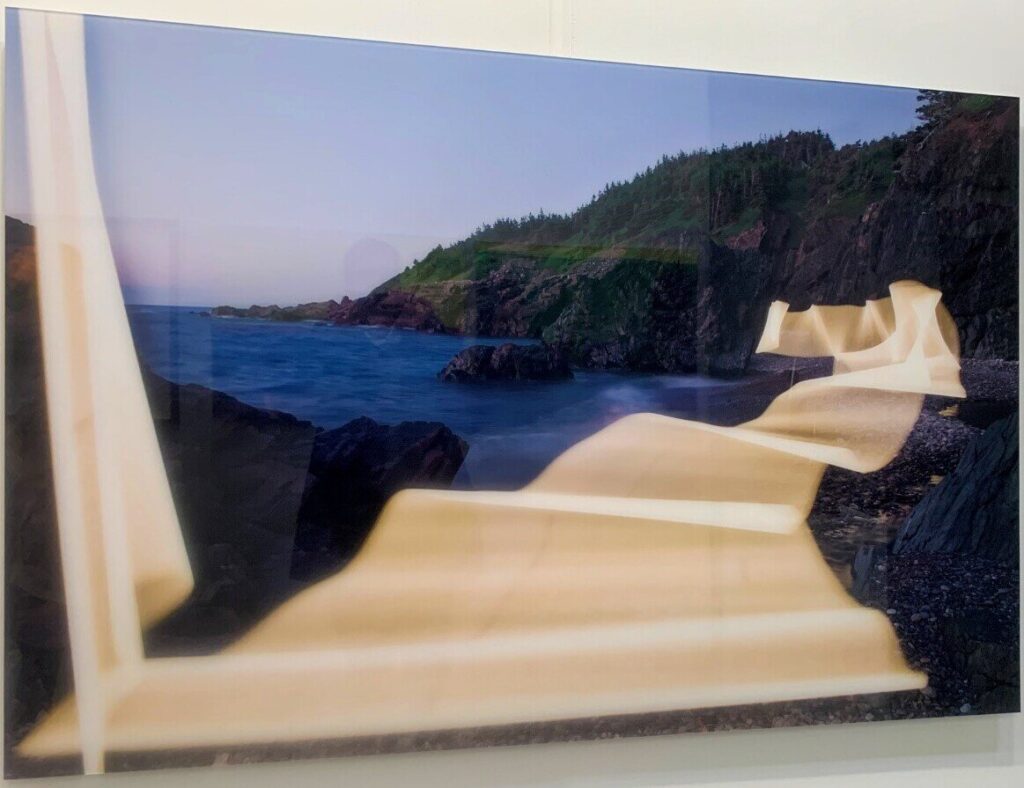

Vicki DaSilva, Magic Cove 1/3, C-print mounted on aluminum, Studio 21 Fine Arts, Halifax

Studio 21 presented work by Vicki DaSilva who has made large scale photographs with mysterious, diaphanous light elements that flow through landscapes. A little video monitor mounted on the wall explained the process. The photographs are long exposures, and the artist has walked through the space with a glowing wand thereby ‘painting’ the elements into the image.

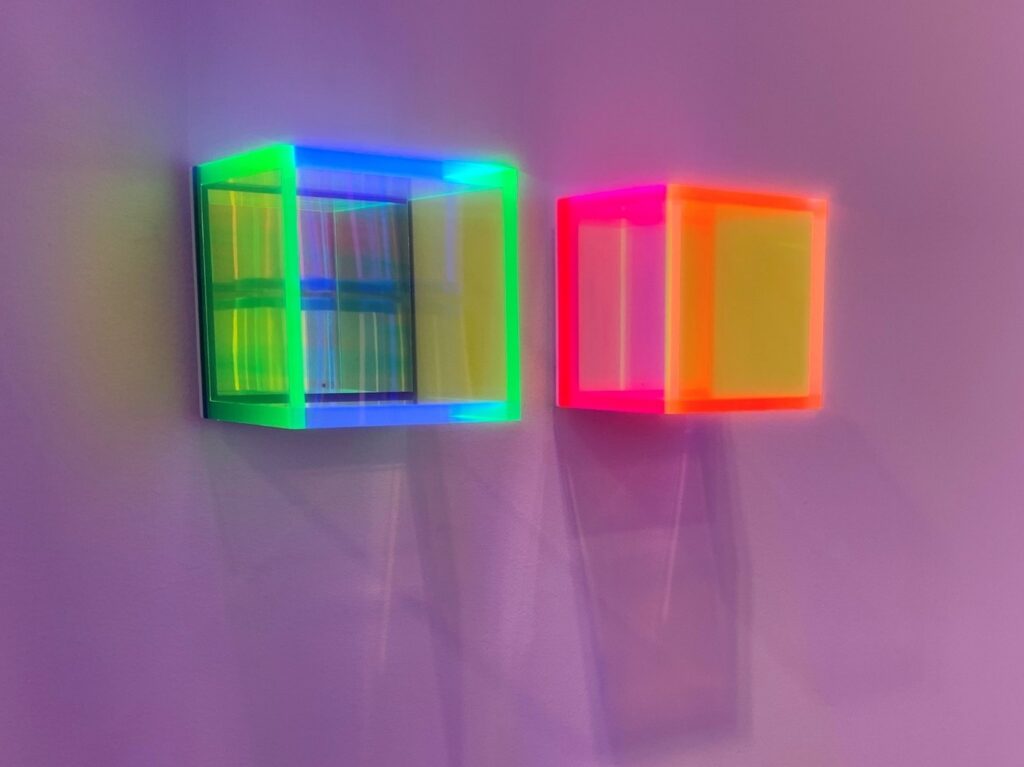

Regine Schumann, Colormirror Sculptures, Axel Pairon Gallery, Belgium

In the Axel Pairon Gallery booth acrylic boxes glow from within with fluorescent coloured light. Colours, refractions, and reflections change at different angles of view. Where does this light come from? There are no visible lamps or wires. Looking up, you’ll see the source – UV lamps are causing these pigments to fluoresce, making the work glow from within.

Eric Nado, Reassembled typewriters, Galerie C.O.A, Montreal

Galerie C.O.A. had a set of machine guns mounted on the wall. Real guns? No. Looking closer, I soon realized they were made from old typewriters that have been disassembled and rearranged. A stark warning perhaps, that words and violence are not disconnected.

Steve Driscoll, Desperate for Their Brightness, 2022, Digital Print On Laminated Low Iron Glass, Backlit LED Lightbox, Peter Robertson Gallery, Edmonton

The Peter Robertson Gallery had a large backlit work by Steve Driscoll. Based on a landscape scene, the colours glowed with acidic brightness. Brush marks and scribbles appeared as though they have been directly applied to the glass. But, as it was explained to me, this is a photographic process. The image was blown up from a smaller original and printed onto this transparent medium. The resolution is so fine that there are no pixels or other evidence of digital manipulation visible.

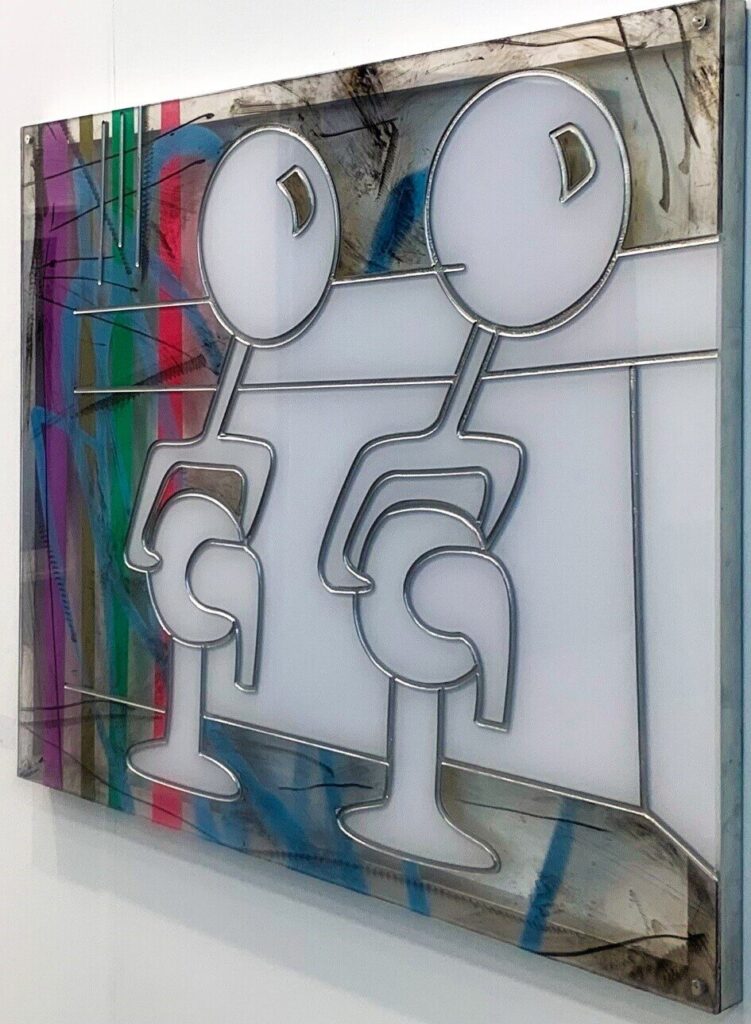

Joe Fleming, White Taps, oil on polycarbonate, 35” x 27”, General Hardware Contemporary, Toronto

General Hardware Contemporary had work by Joe Fleming who paints on transparent polycarbonate panels. This material allows him to paint on both sides of the thick surface. Transparent sections bring out shadows on the wall behind, and grooves into the surface itself allow Fleming to make objects that merge 2D painting and 3D sculpture: a kind of 2.5D space.

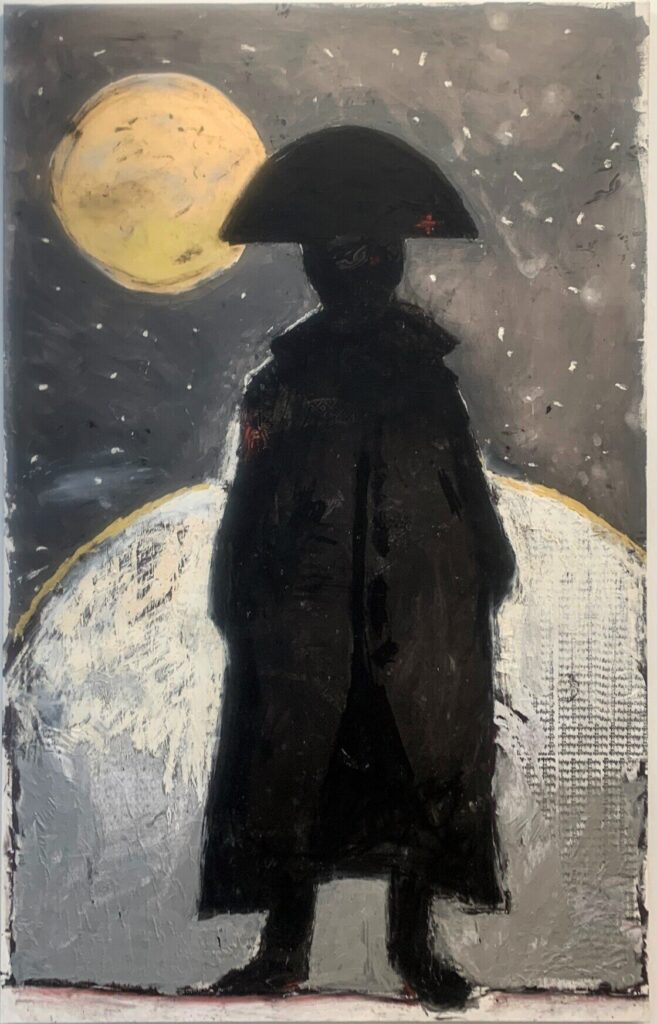

John Scott, Dark Commander, 2012, Mixed Media on Canvas, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto

It’s not only novel techniques that show best in person. Traditional paintings are meant to be seen up close too. John Scott’s Dark Commander, an ominous cross between Napoleon and Darth Vader, is terrifying in full scale. One foot is on its way out of the picture frame. There are boot prints in the paint as though the artist has tried to kick back at this menacing spectre, to stop this world destroyer.

Rae Johnson, Stairs Snow, 2017, Graphite and oil on canvas, Christopher Cutts Gallery, Toronto

Over at Christopher Cutts Gallery’s booth there were a couple of Rae Johnson paintings. Just like John Scott’s work, the digital reproduction does not reflect the full impact of the soft feathery brushwork in Stairs Snow which dissolve like clouds on the canvas.

It makes such a difference to see art the way artists intended – up close and personal!

Mikael Sandblom