Marcel van Eeden’s Imaginary Art Heist

Clint Roenisch has a knack for attracting great talent, and this time is no exception. On display in his gallery are works by the Dutch artist Marcel van Eeden – an artist who has shown in very many prestigious venues around the world.

As Shakespeare’s Prospero famously describes it, our ‘little lives’ are “rounded with a sleep” (The Tempest, 4.1). In general, one might say that we were asleep before our birth and return to sleep upon our death. Following from this thought van Eeden understands history as the time before he was alive, namely before his birth on 22nd November 1965. Moreover, van Eeden has chosen to make art only about the world before his time. He has, for thirty years or so, excluded any references to events that have occurred since this date. Why? He defines the time before his birth as non-existence, and explains that he works with this non-existence as a way of becoming accustomed to the idea of there coming a time when he will ‘non-exist’ again. That, he claims, gives him comfort.

Marcel van Eeden, Stolen Pictures, exhibition view, Clint Roenisch Gallery

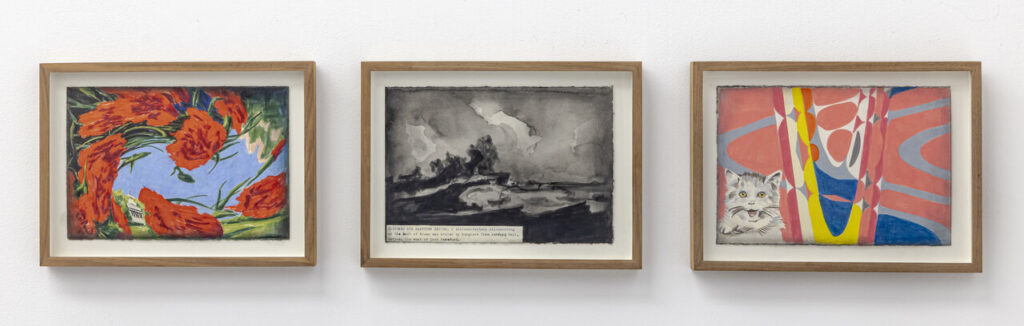

This saturnine attitude to artmaking is reflected in the look of his work, which mainly consists of dark charcoal drawings. His sources, fittingly, are graphic materials from newspapers, books etc., which are predominantly black and white, given that they predate the ubiquitous use of colour images. Interestingly, his focus is on the decades immediately preceding his birth. As he admits, there is a lot of material concerning the time before his birth, and so he tries to make his task manageable in this respect. Further, he is influenced by film noir genre of this period. No doubt the genre chimes with his own predispositions.

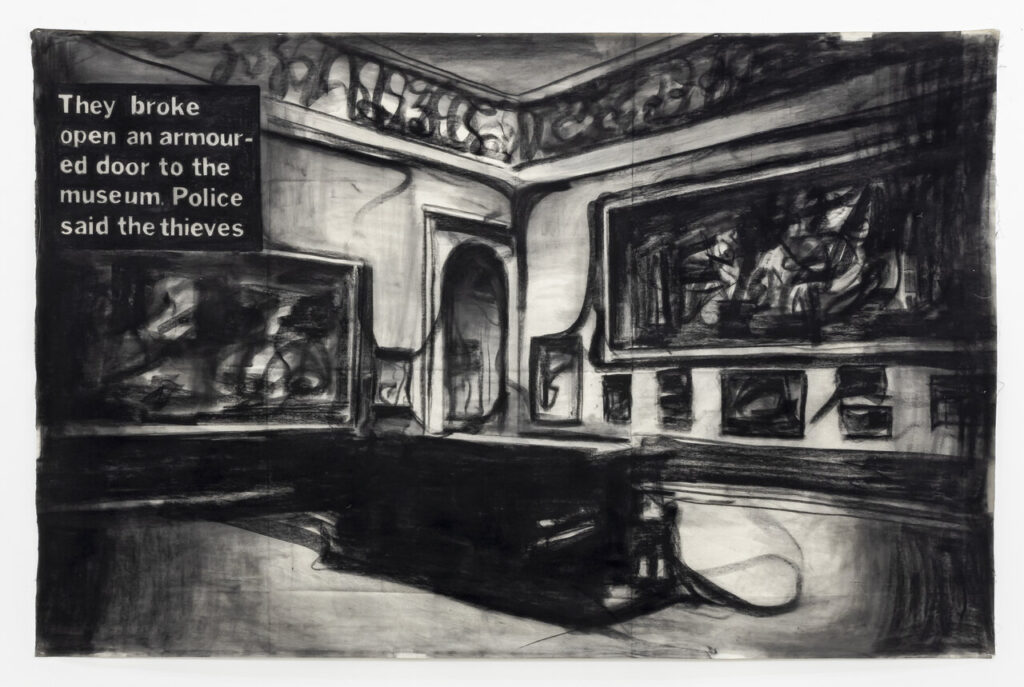

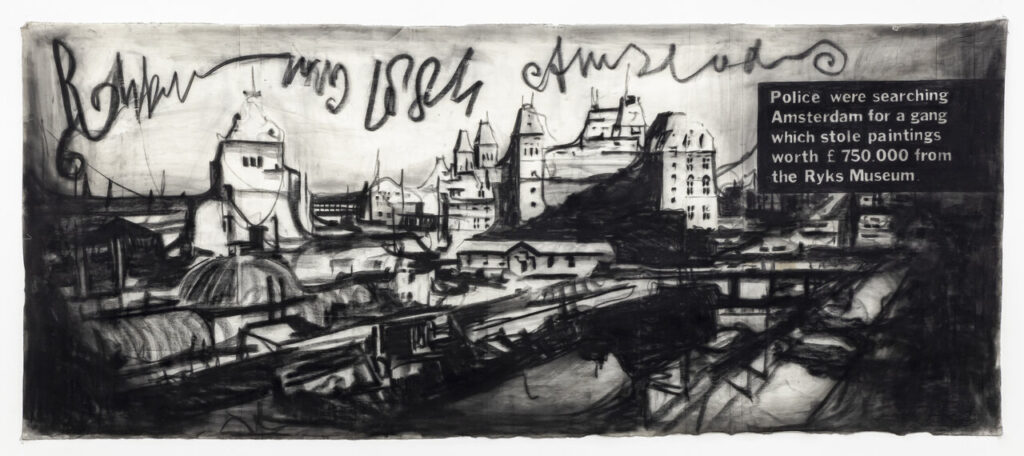

Marcel van Eeden, Untitled, 2020, compressed charcoal on canvas, 165 x 255 cm

Van Eeden has also mimicked film noir by incorporating crime stories into his work. More precisely, he has invented characters around which he has constructed stories the materials from which were originally lifted from books, magazines etc. Two of his fictional characters go by the names K. M. Wiegand and Oswald Sollmann, for example. Both are based on real people. Wiegand was a botanist and Sollmann is based jointly on a pharmacologist, Todd Sollmann, and John F. Kennedy’s assassin Lee Harvey Oswald no less. Each leads a swashbuckling life full of crime and adventure. Often van Eeden has published books, loosely describable as graphic novels, that depict their adventures using short quotes and drawings.

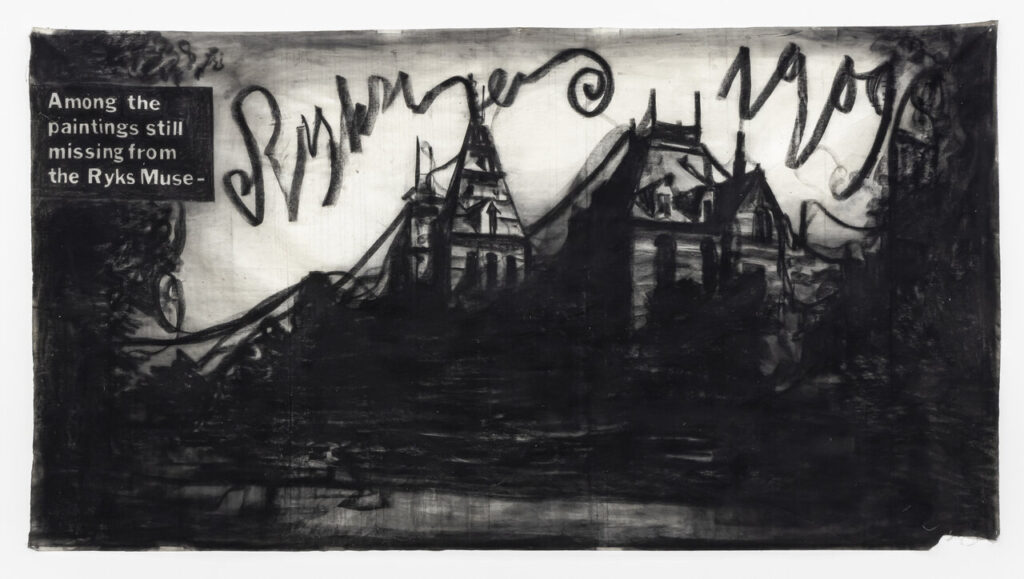

Marcel van Eeden, Untitled, 2020, compressed charcoal on canvas, 165 x 258 cm

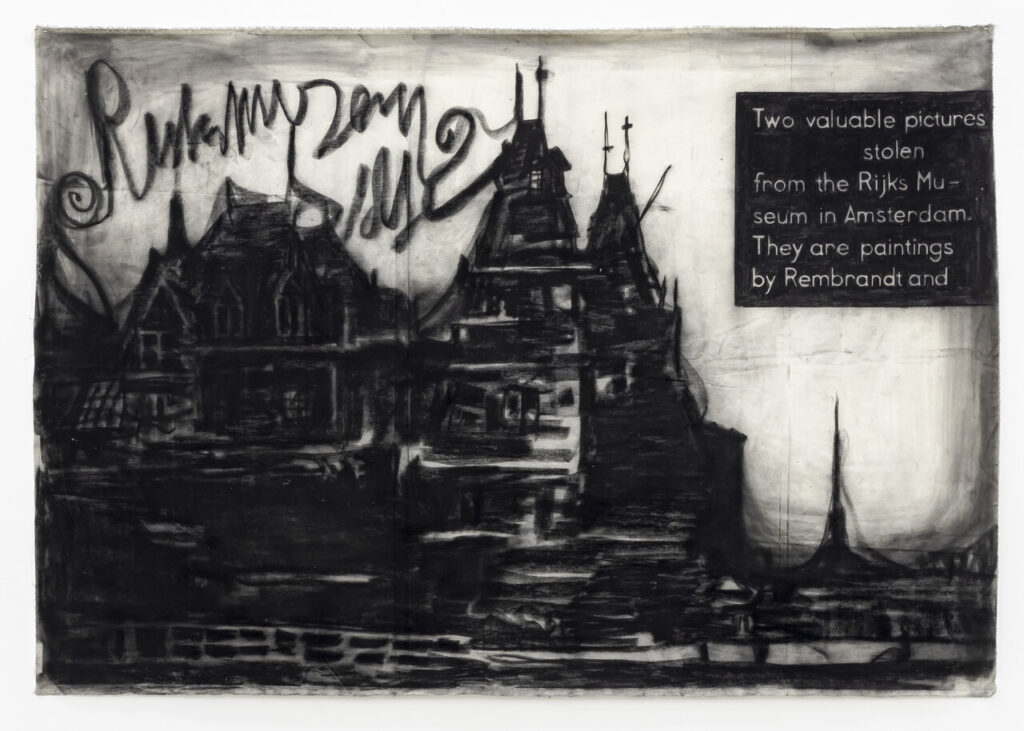

The works in this exhibition centre around a protagonist by the name of Dr Mac Intosch. He has acquired a device known as ‘Zigmund’s machine’, named for its inventor Gert Zigmund (his name is an anagram of the names of two actual electronic companies originating in Fürth, Germany – Grundig and Metz). This machine is designed to extract the Will from various objects. In this exhibition the story goes that Dr Mac Intosch steals two paintings, one by Rembrandt and the other by van Ruisdael, from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, in the belief that the extraction of the Will from artworks is easier.

Marcel van Eeden, Untitled, 2020, compressed charcoal on canvas, 165 x 251 cm

Here van Eeden bases his story on the metaphysical theory of Arthur Schopenhauer as presented in his book The World as Will and Idea. In it Schopenhauer advances a secular idealism. Idealism is the view that the world as we perceive it is entirely the product of our own minds – nothing exists beyond our perceptions. Originally it was assumed that God is ultimately responsible for ‘causing’ the perceptions we each have. But according to Schopenhauer’s idealism what guarantees that your and my perceptions are about the same world, so to speak, is not God, but is instead the driving force behind the world, namely the Will, which we all share. He chooses to use this term because it denotes what we each apprehend as that which animates our bodies. We both see our behaviour of drinking a glass of water, for example, and directly experience thirst and a desire to drink etc. The latter is a private episode that describes the Will. But this Will, for Schopenhauer, belongs to everything in the world – from each of us to trees to rocks. It is the driving force of existence one might say.

Marcel van Eeden, Stolen Pictures, exhibition view, Clint Roenisch Gallery, Front Gallery

So in the story Dr. MacIntosch possesses this diabolical machine that can extract the Will from any object, where the Will is here thought of as energy essentially. The idea of Will as energy is a misrepresentation of Schopenhauer’s theory, but all the same van Eeden uses it to good effect in his story. In the exhibition we are treated to a series of five large charcoal drawings depicting various scenes connected with this art theft. Each drawing includes a caption related to the story. As well, in the front gallery hang a series of smaller drawings on the theme of art thefts.

Marcel van Eeden, Untitled, 2020, compressed charcoal on canvas, 165 x 399 cm

It is perhaps no accident that van Eeden portrays his protagonist as stealing artworks. Schopenhauer indeed thought of art, or its contemplation more exactly, as the nearest we get to understanding the Will, construed as the world as Idea. Here, Idea refers to the world independent of our perceptions, so the Idea of a rose, for example, is its essence in the sense of being stripped of all the incidental properties that the roses we perceive have. Ironically, we can understand van Eeden’s work in this way. Van Eeden aims to depict that which he could never have perceived, i.e., the world before his time. Insofar as he does depict it he reaches for the Ideas behind these events. At least I see this as a useful way of appreciating van Eeden’s work.

Hugh Alcock

Photography: Toni Hafenscheid / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Clint Roenisch Gallery

*Exhibition information: Marcel van Eeden, Stolen Pictures, September 23 – November 27, 2021, Clint Roenisch Gallery, 190 St Helens Ave, Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed – Sat 12 – 5 pm.