The front and back spaces of the Angell Gallery are currently showcasing the latest works by Gavin Lynch. Lynch was born in Northern BC, educated at Emily Carr and the University of Ottawa, and now lives across the river in Wakefield, Quebec. In the last decade or so Lynch’s subject matter has mainly been landscape, more specifically ‘depictions’ of forests, though Lynch’s paintings are not traditional depictions of the forest. At first glance they seem like straightforward scenes, but quickly the viewer notices that their pictorial elements are rendered as flat abstracted surfaces, creating the overall effect of a collage.

Installation view of Gavin Lynch, Mixed Greens. Photo: Alex Fischer

Specifically on display in this show is a more diverse set of images, hence the choice of the term ‘mixed’ in the title one assumes. They are ‘green’ in the sense that paintings are still loosely based on nature – images of wild flowers and abstractions that allude to landscape. But nature is not the defining influence of these works. In a black and white painting titled The Skeleton Dance, for example, we are treated to a composition based on Henri Matisse’s cut-outs of dancers.

The Skeleton Dance, 2020, acrylic and airbrush on canvas, 48″ x 72″

Similarly two abstractions – Nouveau Paysage and Pavillion – incorprate Buren inspired green stripes. There is a certain irony in this choice given that Daniel Buren’s ubiquitous stripes were a sort of declaration of the end of painting.

Nouveau Paysage, 2020, acrylic and oil on canvas, 72″ x 60″

Pavillion, 2020, acrylic, watercolour, and airbrush on canvas, 35″ x 65″

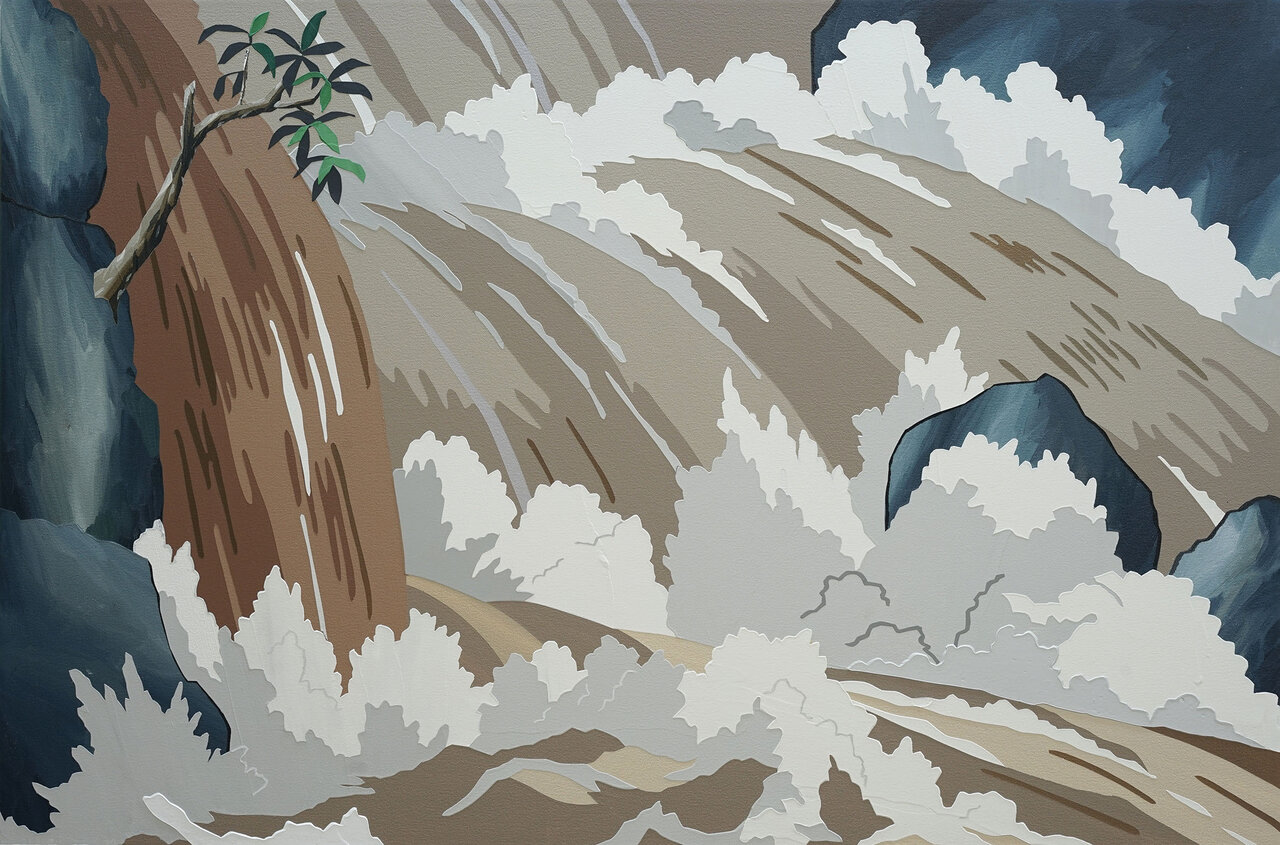

Two other paintings – Reanimating the Falls and Leaving Emishi (Ashitaka’s Falls) – that depict a waterfall, are nonetheless not derived from nature. They are based on images from a film by the Japanese animation studio Ghibli, directed by Hayao Miyazaki. This conflating of the real and simulation is by all accounts a deliberate strategy of Lynch’s. The idea was made famous by the French social theorist Jean Baudrillard, whose term ‘simulacra’ (i.e., simulated versions of reality) Lynch uses to describe his work. Moreover, Lynch seems to embrace Baudrillard’s notion of hyperreality. The hyperreal describes that which is more real – more alluring – than banal reality. Indeed, our postmodern condition is characterized by our inability to separate the two domains – they merge into one. Ghibli studio’s creation exactly illustrates this idea. The studio’s reimagining of a land inhabited by an historical tribe called the Emishi inspired a company to build a physical version of one of their villages in the Mie Prefecture in Uga Valley, Japan. Here history and fantasy are conflated.

Reanimating the Falls, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 60″ x 72″

Leaving Emishi (Ashitaka’s Falls), 2020, acrylic on canvas, 24″ x 36″

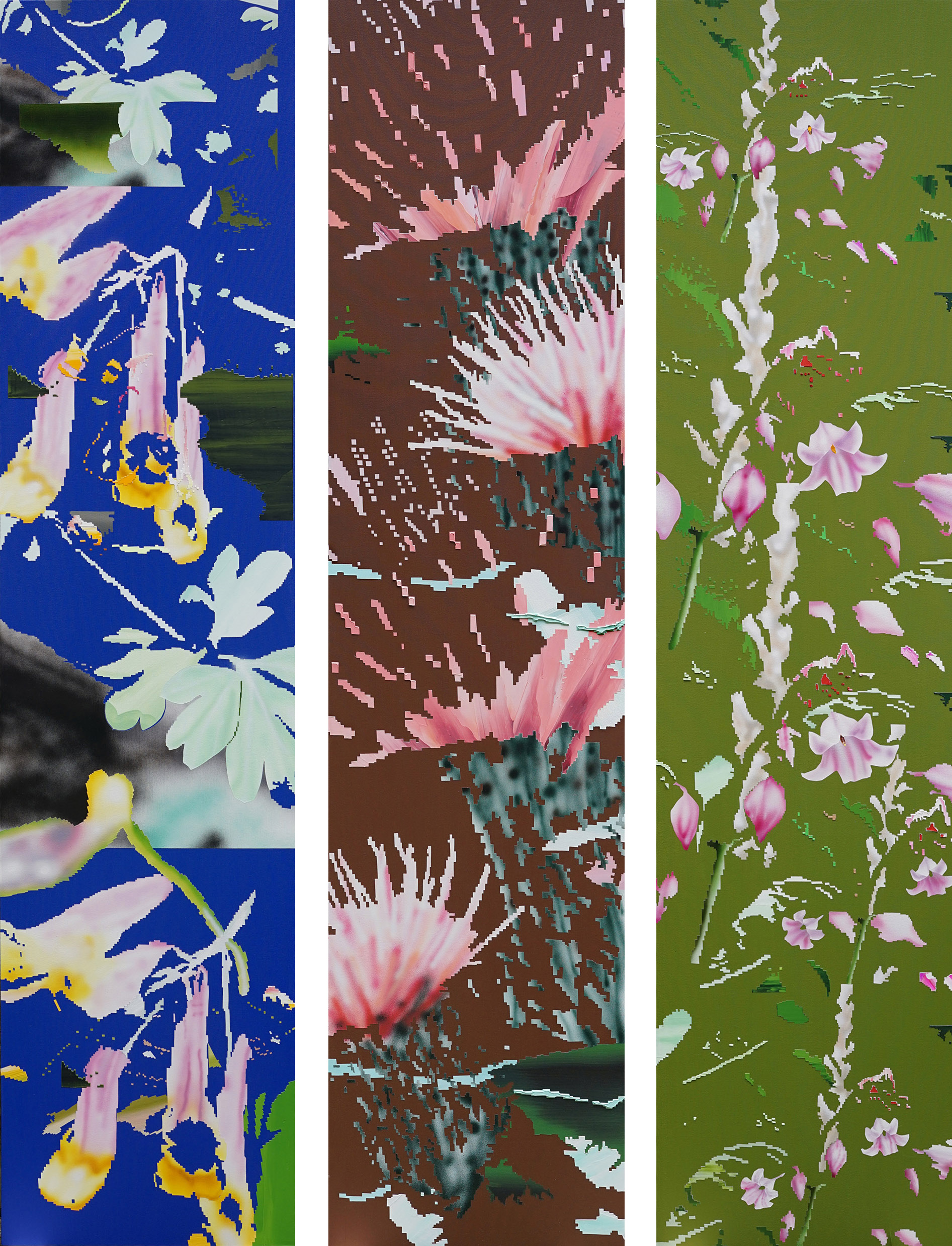

On one wall hang three vertical scroll-like paintings which are ostensibly depictions of endangered Canadian wildflowers. At least that is what their titles suggest – Dogbane, Pale Corydalis and Pitcher’s Thistle. But the subject matter turns out to be largely incidental. Lynch has taken images of these flowers and manipulated them with computer software. It is these manipulated images that are the starting point for the paintings themselves. Lynch tells the catalogue essay writer Bill Clarke: “So, the resulting paintings appear…glitchy.”

Pale Corydalis (left) Pitcher’s Thistle (center) and Dogbane (right), all three 2020, acrylic and airbrush on canvas, 92″ x 22″

Terms like ‘glitchy’, ‘pixelated’ and ‘low res’ of course get their meanings through the ubiquitous screens by which our world is now mediated. And indeed, Lynch’s work might plausibly be described as screen-based in this sense. The screen has become the ultimate vehicle, Baudrillardian hyperreality. What we see on the screen and what we see in the physical world is becoming more and more difficult to distinguish. Lynch exploits this fact.

The result is a techno-aesthetics. Lynch celebrates the world not as it appears to us on the screen, but the world of the screen. The screen-flatness of his imagery is made explicit by his use of paint on canvas – that old-time technology. That is why, I am guessing, he often uses impasto – to accentuate the materiality of the paint in contrast to the cool flatness of screen imagery.

Installation view of Gavin Lynch, Mixed Greens. Photo: Alex Fischer

These paintings are sophisticated in their composition, execution and the thinking behind them. And the passages of paint are exquisite at times. But I wonder what in the end Lynch is expressing by them. In some of his landscapes there are moments when the viewer is drawn in to the scene, where the scale of the land is made palpable for example. Yet, ultimately the viewer is pulled back to the flat surface that epitomises Lynch’s aesthetic. The screen flattens our world figuratively as well. That is, it makes our experiences mediated by it alike in some qualitative sense. What they are about falls away. All that remains is the allure of their superficial appearances. Everything reduces to spectacle. For Baudrillard ascendance of hyperreality is apocalyptic – he never shied away from hyperbole. It spells the disappearance of the subject, where we become instead nodes in an endless exchange of signs and nothing more. I sense none of this darkness in Lynch’s embrace of the notion, however.

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of Angell Gallery

*Exhibition information: September 24 – October 24, 2020, Angell Gallery, 1444 Dupont Ave, Unit 15, Toronto. Gallery hours: Open by appointment only