The Propeller Art Gallery is currently hosting an exhibition of drawings. It is the result of an open juried call. The curators – Joseph Muscat and Keijo Tapanainen – encouraged those submitting to ‘stretch the boundaries of the medium’, hence the title of the show Drawing Unlimited.

The two Curators: Keijo Tapanainen (left), Joseph Muscat (right), and Lisa Johnson, Exhibition Co-ordinator (middle)

Installation view of Drawing Unlimited

There are thirty three works on display, all by different artists. But it turns out, rather, that most of the submissions, though not all, fell safely within the boundaries. Most do not challenge the viewer’s expectation of what a drawing ought to be. The normative nature of this expectation points to the fact that it is difficult to push these boundaries since there are no definitive criteria by which to measure such a thing. What should a drawing be? No one can say exactly. Talk of ‘stretching’ these boundaries, then, is apt in the sense that the concept of drawing is elastic.

Maureen Paxton, Rake, 2016, graphite on paper, 30″ x 40″ framed

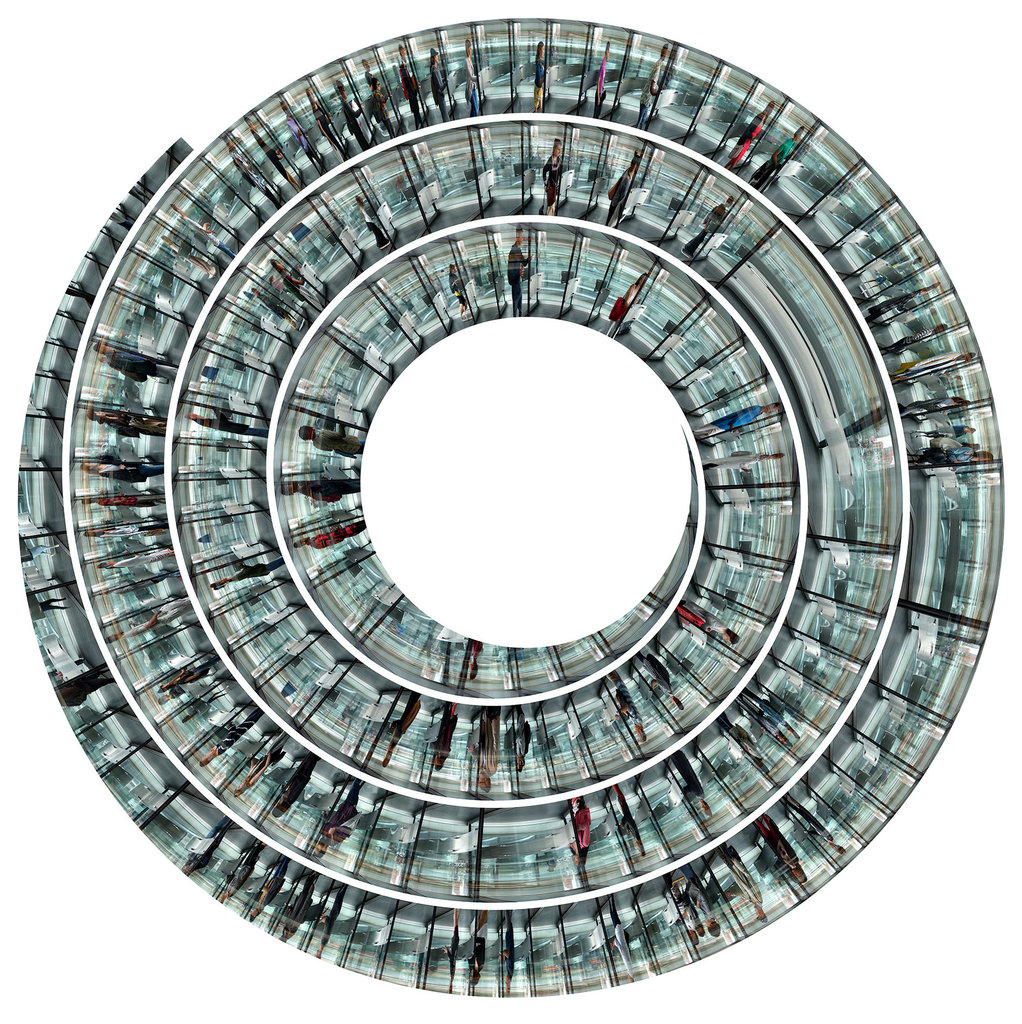

Consider, for example, the submission by Harold Sikkema titled Revolve Face. It consists in a spiral of distorted images derived from a camera aimed at a revolving door. It shows various people pushing on the plate glass on their way in and out of a building. It is in some ways an arresting image, but in what sense is it a drawing?

Harold Sikkema, Revolve Face, 2019, algorithmic video drawing on dibond, 24″ x 24″

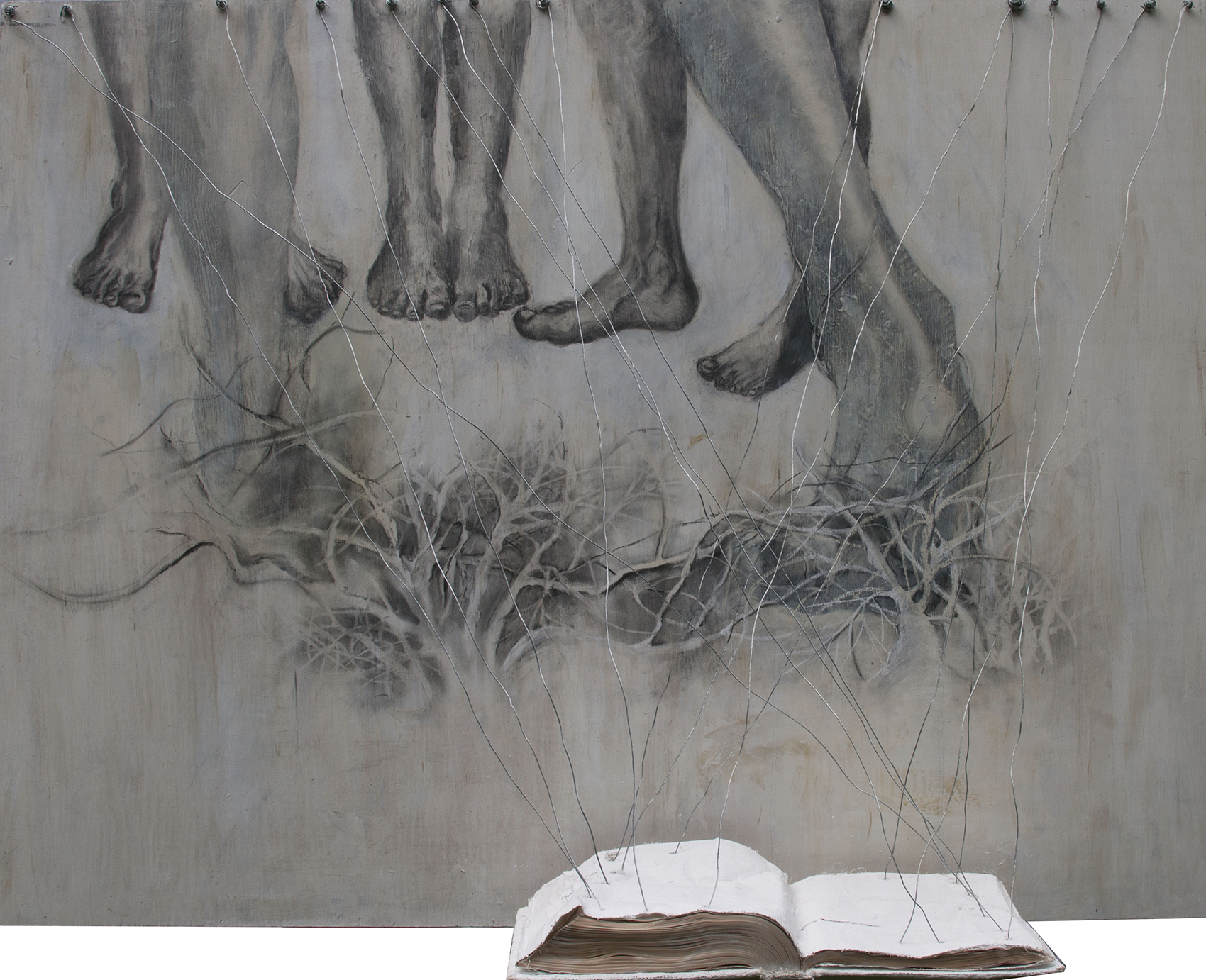

Pnina Dinkin’s piece, Change is needed in construct of His-story, depicts four pairs of bare feet and attached along the top are a series of wires that suspend a blank book at the base of the board. Certainly, it has a drawn element, but the overall work is best described as a sculpture of sorts. But then again, the wires could be interpreted as lines belonging to a three-dimensional drawing. Who is to say that drawing is two-dimensional in nature after all?

Pnina Dinkin, Change is needed in construct of His-story, 2019, charcoal on plywood, gel medium, wire, book, plaster, 36″ x 48″

While drawing cannot be precisely defined, the curators proffer a description of what we aim to do when drawing. Citing Anna Moszynska, they explain that it is ‘a direct and immediate method of trawling the imagination, unlocking the collective and personal unconscious…It allows the hand to give free expression to that which is buried in the recesses of the mind…’. This is an apt characterisation of what most of the works attempt to do perhaps – to mine the unconscious. I take this to mean that the artist is attempting to give expression to what she intuitively feels rather than what she thinks, that is, what is otherwise expressible in words, i.e., conceptually.

Melissa Arruda, Anxiety Drawing #4, 2020, ink on bristol board, 30″ x 40″

This idea echoes the views of the enlightenment philosopher and a principal founder of modern aesthetics, Immanuel Kant. Kant argued that the genuine artist – or ‘genius’ as he put it – is able to liberate our perceptual faculties from their innate conceptual constraints. Doing this is called the ‘free play of the imagination’, where the imagination is our innate faculty to build the phenomenal world. He maintained in this regard that appearances, i.e., phenomena, are not passively received by us but rather are essentially constructed by us. Ideally, then, the artist according to Kant aims to represent the phenomenal world in a way that encourages the viewer to see things in a way that is free from how we naturally see the things around us – to nudge us from our predictable way of categorising the world under our concepts. And it is in this way that drawings can stretch us, to continue our metaphor. Our experience of beauty derives from the pleasure of this free play.

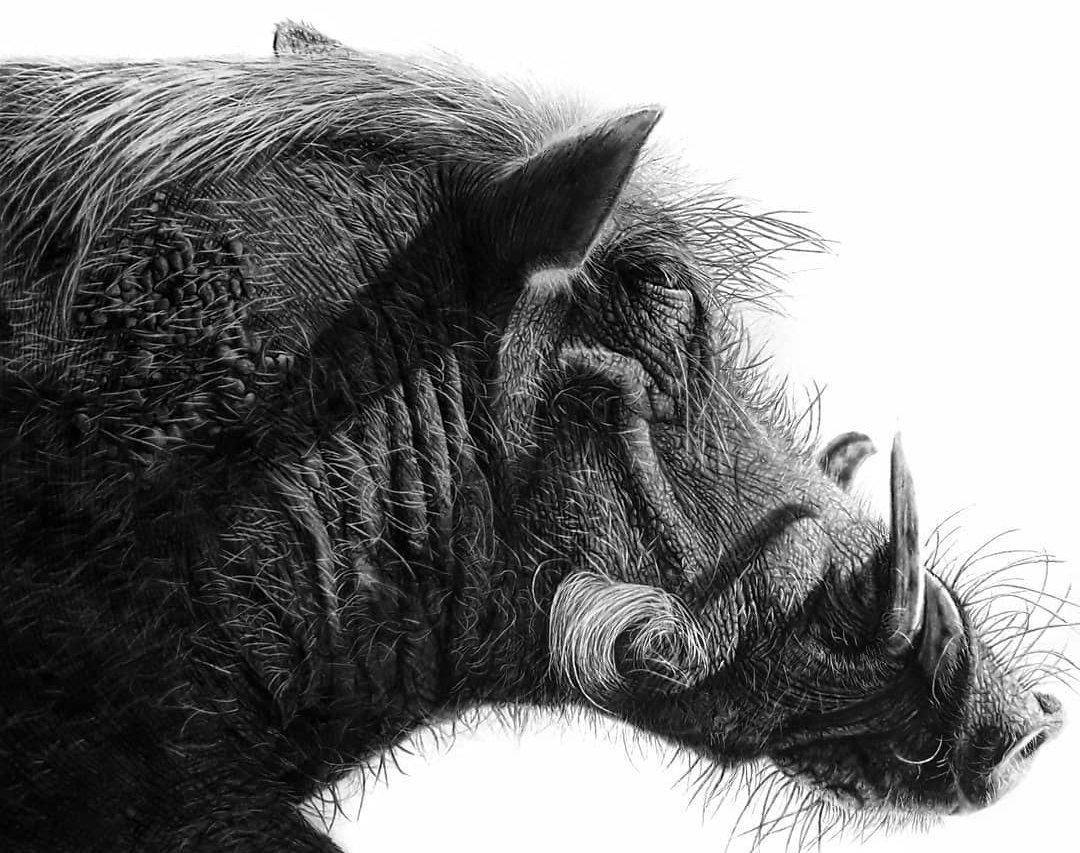

In terms of the drawings in this show, while many of them are pleasing to the eye, few engender a sense of beauty in the way Kant describes it. That is, the drawings as a rule do not seriously challenge our ways of seeing the world, do not stretch us. This is evident, for example, in Lisandro Pena’s Warthog which is a delectable rendering of the animal. Nonetheless it doesn’t shake up how we see the world in any stimulating way. I do not pretend to suppose that Kant here offers the way of evaluating the artworks, but his ideas can help in a small way.

Lisandro Pena, Warthog, 2018, pencil and carbon, 11″ x 14″

But let’s not be too earnest. This is a lovely collection of drawings. They include intimate portraits, delightful landscapes, a relief on wood of the pelvis bones expertly rendered and a homage to Gaudi in the form of a small drawing in ballpoint pen. The exhibition has been masterfully hung to juxtapose the drawings in a stimulating and thought-provoking manner.

Installation views of Drawing Unlimited

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of Propeller Art Gallery

*Exhibition information: February 19 – March 8, 2020, Propeller Art Gallery, 30 Abell Street Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed – Sat 12 – 6 pm, Sun 12 – 5 pm.