Ghost stories are often told around a campfire, but for Alex McLeod, they are told basking around the glow of a computer screen. Ghost Stories at Division Gallery is an impressive undertaking that significantly adds to the artist’s body of work, both in terms of new artworks and conceptual underpinnings.

Installation view of Alex McLeod, Ghost Stories at Division Gallery. Photo: Nathan Flint

McLeod’s artistic practice has often been associated with post-internet aesthetics and a self-reflexivity of the media he has used to generate his work. Inspired by the fragments, remnants and subtle elements of computer-generated imagery, McLeod explored and celebrated the ephemera that traditional 3D animators and video game designers would overlook.

In Ghost Stories, McLeod pushes this exploration closer to its logical conclusion; what does the end look like for these digital artifacts? Can data experience death? What are the connections and disconnections between the simulation and what is being simulated? How can we memorialize the code that has been deleted, abandoned or lost? Do pixels believe that we are their divine creators? These are the questions that this exhibition asks its audience to ponder while being captivated by the mesmerizing movement and psychedelic palette of McLeod’s latest body of work.

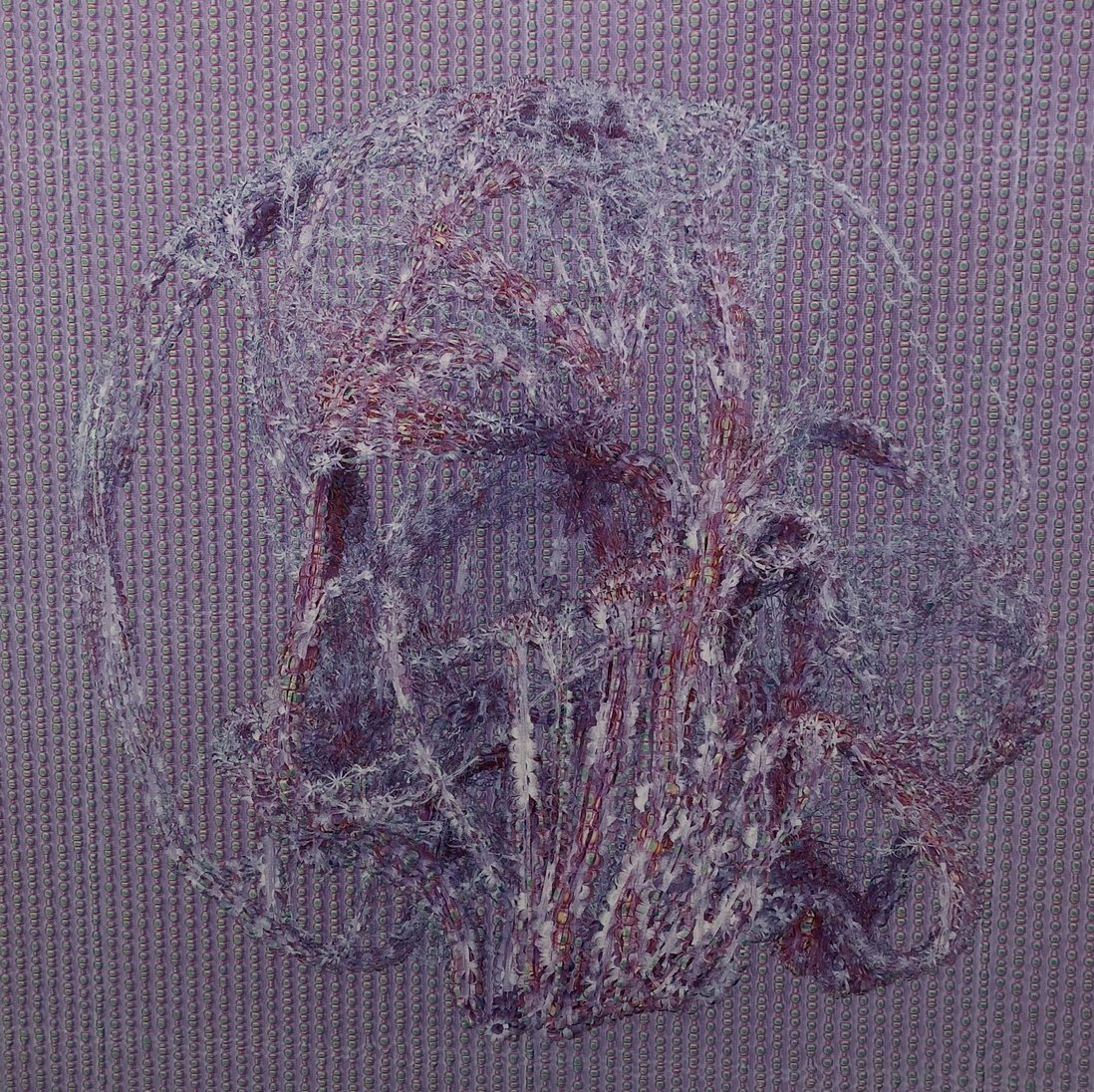

Alex McLeod, Skull, 2019. Photo: Nathan Flint

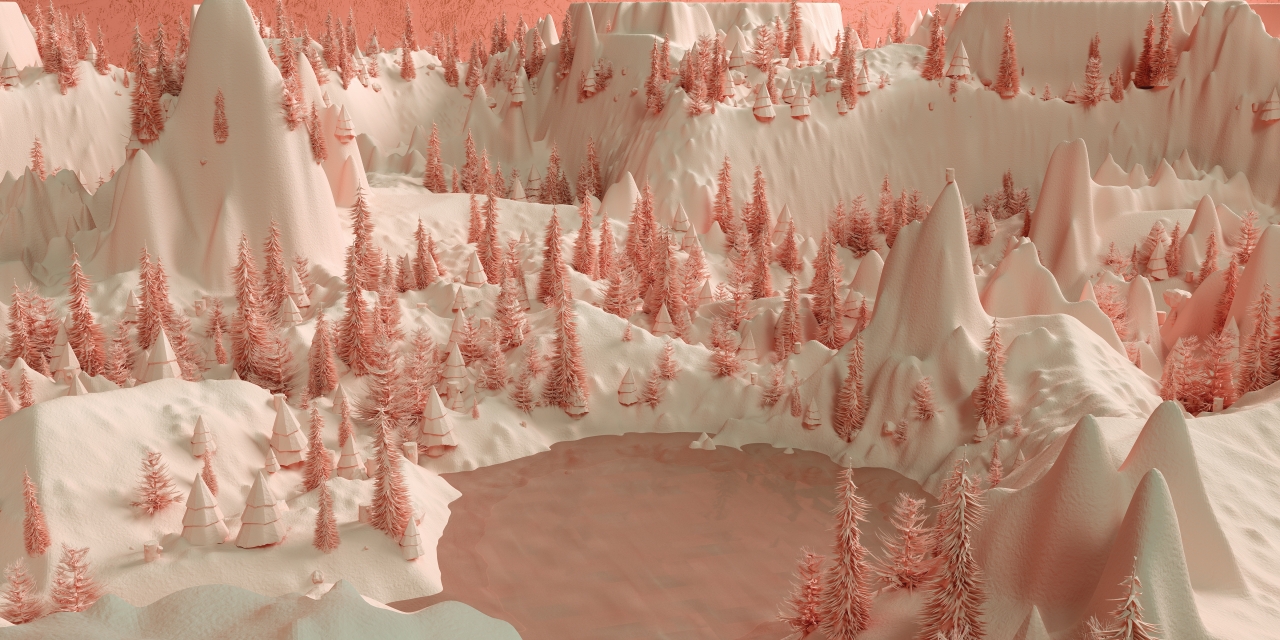

The first piece that drew my attention in the exhibition was Pinkhills, a large scale C-print of a monochrome pink landscape. The topographical features, such as the hills in the image, are simultaneously too smooth and erratic to feel real, while one of the two forms of trees scattered throughout the image resembles toy-like models, and the remaining trees are generated with naturalistic realism. The variety of styles adds a dimension to the simulation as there are both canny and uncanny elements, which create both tension and a spectrum between reality and virtual. The landscape felt evocative of photographer Richard Mosse’s series Infra from 2011, where the artist took infrared photography of the Congo to draw attention to the conflicts the country has been facing. Similarly, this particular work of McLeod’s felt like an homage to the hidden histories of landscapes, but within a CGI context. This cotton-candy fairyland could have been the site of violence or massacres in a first-person shooter game or could be a remote location in a map that was never explored in a role-playing game.

Alex McLeod. Pinkhills, 2019. Courtesy of Contact Photography Festival

Another piece titled Green Landscape uses similar aesthetics, contents and perspective, with the notable exception that it contains multiple colours. The vibrant pink, oranges and red pop in contrast against the bright green and blue of the grassy hills and lake. The image is a fun and whimsical fantasy world that feels like a blend between a LEGO playset, the popular video game Minecraft and the set of a Claymation feature film. Each of these large landscapes tap into the sublime feeling of a digital world too vast to comprehend, as well as the nostalgia of an early Millennial’s youth.

Alex McLeod, Green Landscape, 2019

All of these images are absent of humans or animals. This choice seems deliberate as if to imply all the users and Non-Player Characters (NPCs) are gone, in a digital post-apocalyptic vision of a virtual world. If people no longer exist in the real world, it seems obvious to assume that the natural environment would thrive, but can the same be said about a digital environment? Might these artificial lifeforms evolve or perish, and what would each of these scenarios look like for them? Digital environmentalism could become part of the critical discourse of the future as the seemingly infinite expanse of the Internet and technology reach finality, making preservation, sustainability and diversify new priorities.

The next set of works are Illusion #1, #2 and #3. These challenge perspective through their unconventional canvas shape and warping of the image. The close ups of 3D objects are on a flat natural plane, while the expansive landscapes are stretched into rhombuses and quadrilaterals to create the perception of depth from a one-point perspective. The expansive landscapes look miniscule while the 3D objects appear macroscopic. The juxtaposition of size and perspective create an optical illusion that these flat canvases are in fact jutting away from the wall. This optical illusion is self-reflective in the medium being employed since what we refer to as 3D objects in virtual space are just illusions of depth from a 2D screen.

Installation view with Alex McLeod, Illusion #1, Illusion #2, and Illusion #3, 2019. Photo: Nathan Flint

This notion of the 3D object in virtual and real space, continues in the exhibition, particularly with the work Coral Lands and accompanying sculpture Friends. Coral Lands is a large vertical image that acts as an imaginary window in the gallery looking out onto a vast rendering of orange hills covered in tiny polyps. Just in front of this work, sits Friends, a synthetic sculpture of one of these polyps with a pink flower on top, as well as a round shell-like object, both on top of a flat, blue puddle-like shape. The sculptures in the group in front of the picture provide a translation from the real into the imaginary and simulate the environment of Coral Lands penetrating into the gallery space by Friends.

Installation view of Alex McLeod, Coral Land and Friends. Photo: Nathan Flint

Elsewhere in the gallery are a collection of sculptures similar to Friends, but individually placed on plinths. Each of these objects have a materiality reminiscent of the common texture settings within 3D modelling software, such as highly reflective or flowing fur. These objects are normal when seen through the mediation of a screen, but to see them in real life gives them a different form of agency where they beg to be touched just to prove that they are real.

Alex McLeod, Studded Cloudstack, 2019. Photo: Nathan Flint

Installation view. Photo: Nathan Flint

Last, a collection of video screens adorn the wall in a horizontal pattern of monitors alternating between landscape and portrait orientations. Displayed are short looping videos of computer-generated animations. These animations are seamless loops that ebb and flow infinitely. Some seem to reference organic shapes. Others appear like pottery moving on an invisible lathe or a stroboscopic sculpture with a shape that could be a result of our eye being unable to process the subtle movements fast enough but still producing something solid. There are several references to the Fibonacci sequence throughout the videos, perhaps due to the nature of the hidden mathematics within computer animations. Each video feels as though they began as experiments within the software and then became refined and produced beautiful and satisfying content that hypnotizes with its colour palettes and continuous movement.

Installation view with video screens. Photo: Nathan Flint

Within the context of the CONTACT Photography Festival, the show seemed to propose that we as a culture have reached a point of acceptance of the virtual camera rig built into computer software as a fair competitor or rival for the traditional or digital camera that we can hold in our hands.

Ghost Stories by Alex McLeod is riddled with momenta mori that remind us that while new media technologies may still be in their infancies, we must never forget that everything dies and we hope to learn in time how to prevent it. Visiting this exhibition was like to travelling into an imaginary world filled with bright colours and eerie themes, where the virtual and the real felt as seamless as a looping animated.

Nathan Flint

*Exhibition information: April 11 – June 8, 2019, Division Gallery, 45 Ernest Avenue, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat, 10 – 6 pm.

Part of Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival