Pengkuei “Ben” Huang. Photo: Matz Rios

Interview with Pengkuei “Ben” Huang (BH) by Maria Mendoza Camba (MMC) in the occasion of his solo show at Urban Gallery

In the wake of the Tōhoku tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear disaster that devastated Japan in 2011, Ben Huang forays into documenting the nation’s survival amidst the tragedies’ profound impact. Photographing spaces that were ravaged most over the course of seven years; Huang’s photographs embodied the inhabitants’ resilience and hope despite the inevitable reality of bearing the calamities’ grim aftermath. Here, Huang talks about his process, and his realizations as he recounts the nation’s recovery through his photographic lens.

MMC: How did you conceptualize this project? Where and how did you begin?

BH: It started when I connected with my friends from high school who were originally from Japan. The idea was born out of my curiosity to know how the nation was going to recover from these tragedies.

My dad is also Indonesian-born Chinese and so this tragedy hits me in some ways because of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. This was another reason why I wanted to document Japan’s recovery.

Rikuzentakata, 2017

MMC: Did you have any expectations on your journey of documenting the aftermath of the tsunami and the Fukushima explosion?

BH: Not really, it was a fairly open project. I did some preliminary research about the places I wanted to visit so I knew that it might be difficult to get to those places, especially when you are not an accredited photojournalist. Also, for a short period of time, there was a language barrier. But other than that, I just went with the flow.

MMC: Some of your photos show places that have been impacted by the Fukushima explosion, how did you manage to capture those?

BH: As the time went by, I became friends with photographers from that area who were doing similar projects. Some of them have introduced me to the locals. Through them, I was able to build relationships and document the work they were doing in the aftermath, like searching for missing bodies, and gaining access to the places affected by the tragedies.

The Search Party. Okuma, 2018

MMC: Your work shows juxtaposition between the corporeal effects of the tragedies and the inhabitants who seem to be in the process of rebuilding their lives. What was your aim when putting these images together?

BH: While I was on the ground, I could sense sombreness despite the locals’ hope for the future. So yes, there was a conscious decision to demonstrate a sense of uncertainty.

MMC: In terms of your process, were your photographs accompanied by dialogues or interviews with the locals? Did those aid you in constructing the images?

BH: There were a lot of conversations with the locals. One of the things I ended up doing was to help with a local festival. It was funny how much information I got from having drinks with those people and staying in their houses.

Nomaoi Festival. Minamisoma, 2016

MCC: How did you choose the photographs you would show in this exhibition?

BH: That’s a very good question. It is always diffcult to figure out what to show out of thousands of images. The process is to go through all the photographs first, narrow them down, and then see which ones goes best together. For this project, I started with developing the title.

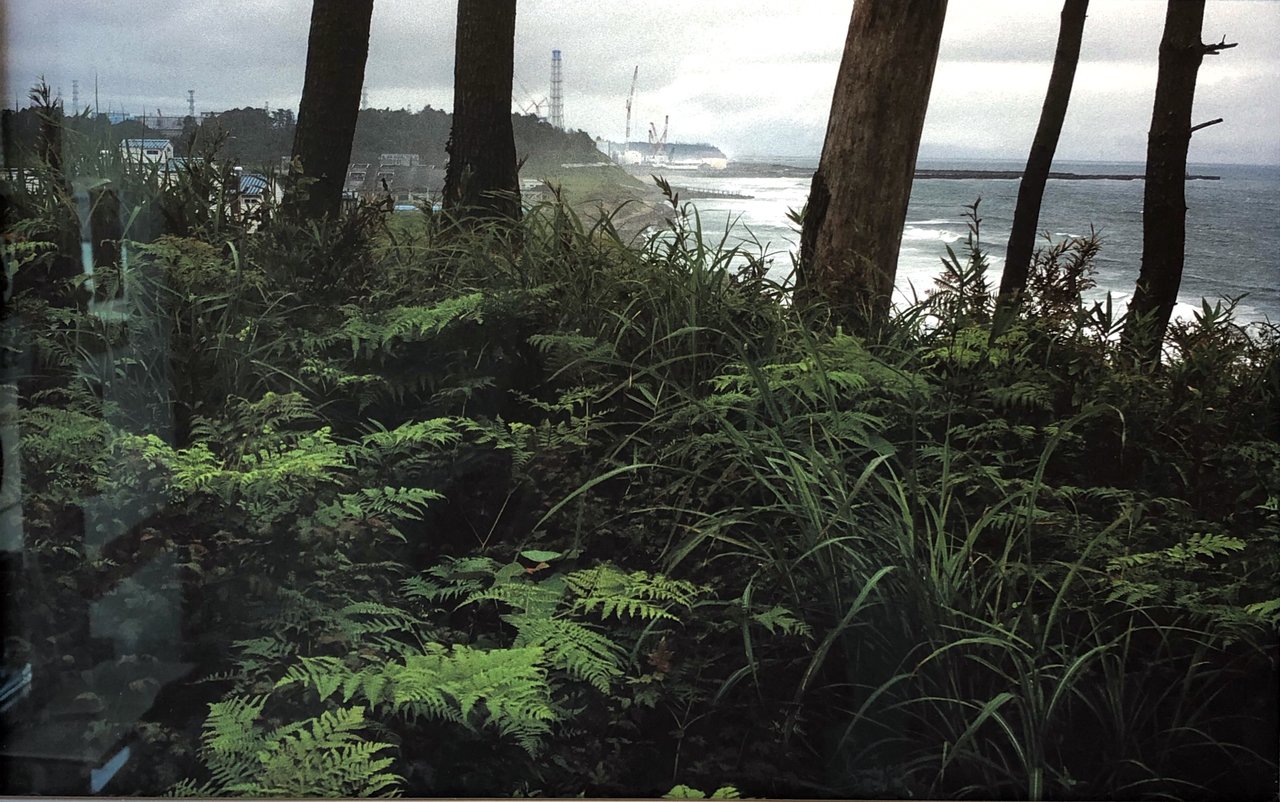

When I went through the images from my journey, I found that there were a lot of surviving pines in the area that endured the 14-meter wave from the tsunami. I saw quite a few of them when I drove along the coast. That area was a well known landmark to the locals. So I choose the idea of Solemn Pines, Fading Things as the title for my show. It captured the combination of things destroyed and others that survived. I felt a strong nostalgia for the past in the locals. Once I figured out the title, I started working on the prints that would convey the idea.

Fukushima No. 1. Okuma, 2017

MCC: Please tell us more about Relics. Okuma, 2016, the photograph that depicts a multitude of clothing.

BH: I was introduced to this man, Norio Kimura, whose house was only 5 kilometers from Fukushima No. 1. He lost three members of his family to the tsunami including a seven-year-old daughter; a well-known story for those who were following the disaster. It was only until two years ago when he found partial remains of his daughter, a piece of her jaw. A friend of mine, a well-known photographer, documented it. On Relics, Okuma those are the clothes that Kimura found along the coast with his daughter’s remains. He decided to live in a nearby temple, built this ‘mountain’ of clothes and in a way it became a memorial site.

Relics. Okuma, 2016

MCC: Was this your first foray into documenting an aftermath of a tragedy?

BH: Yes this was my first project of documenting an aftermath of a tragedy. In terms of nostalgia, it has a certain common thread with my previous projects. For example Fantasyland, my first project, was about theme parks in the States. That idea was born out of my horrible experience. In high school, every year, we had trips to amusement parks. These parks sell a fantasy world but the reality of being there is very different with long lines or kids dating. In some ways, it depicted controlled happiness.

MCC: How do you feel about the progress of your photography, culminating in this project, Solemn Pines, Fading Things?

BH: I learned a lot doing this project, in terms of how I see things visually and how I feel about life. You talk to people, you see things but it was at a different level when I, myself, witnessed and experienced the struggle of the survivors to recover. It definitely transformed me as an individual, as a photojournalist and as a storyteller.

Okirai Port. Ofunato, 2012

Images are all Archival Pigment Print, 16 x 24 inches, courtesy of the artist and Urban Gallery

*Exhibition information: Solemn Pines, Fading Things, May 2 – 31, 2019, Urban Gallery, 400 Queen Street East, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Fri 12 – 5 pm, Thu 12 – 8 pm, Sat 1 – 5 pm.

Part of Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival 2019