Suspend: Tim Whiten’s Spiritual Objects

Entering the Olga Korper gallery is akin to stepping into a sun-drenched church. You push through oversized heavy metal doors into a cavernous skylit space. This is an appropriate venue for exhibiting the idiocratic creations of Tim Whiten, with all their spiritual aura. On display are ten beautifully crafted objects – five wall-mounted and five self-standing. Each is made using primarily natural materials that include glass, wooden branches, leather, shark teeth and human remains.

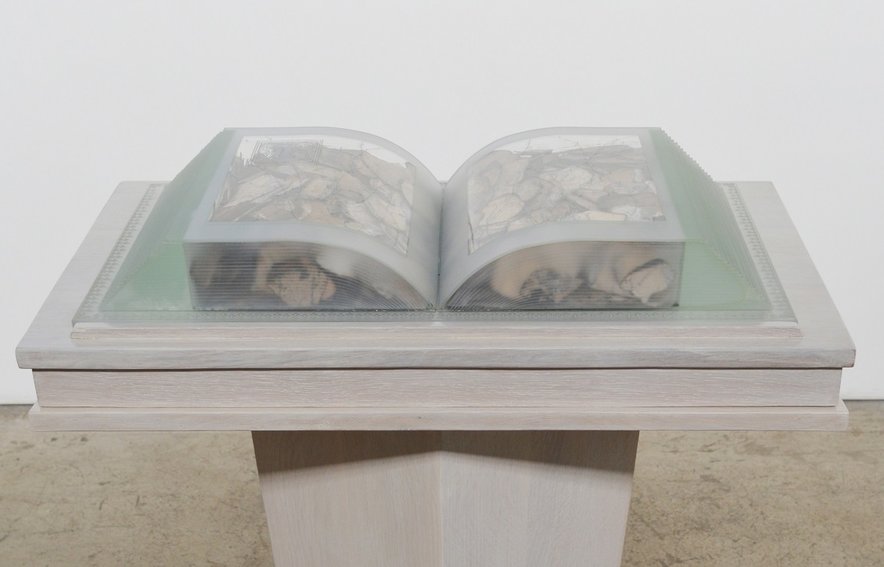

Book of Light: Containing Poetry from the Heart of God, 2015-2019, handcrafted crystal clear glass, fragments of drawings, oak, 46.5” x 28” x 15”

The centrepiece of the show is a semi-opaque glass coffin titled Who-Man/Amen. I describe it as a coffin not only because it takes the form of one but also because it contains the skeleton of a small person, wrapped carefully in delicate cloth. This can be glanced through two portals of clear glass on top. At first I recoiled at learning that these are real human remains. But this involuntary response immediately led me to wonder about the nature of art itself. Whiten’s work induces such questioning. It challenges the very concept of artmaking. Indeed, he is reluctant to characterise himself as an artist, preferring to describe himself as a maker of cultural artefacts.

Who-Man/Amen (detail), 2015-2016, handcrafted crystal clear glass, mixed media with human skeleton, 18.5” x 66.5” x 26.5” (left) and detail of the inside (right)

The human remains were legally procured. I learned that in India in particular there is a vibrant trade in human skeletons because all medical students in the country must invest in a real skeleton. Synthetic copies are deemed inadequate (‘Booming Business in Bones’, The National, United Arab Emirates, 28 Dec. 2015). But while it is excusable to use real skeletons to ensure proper training of medical doctors, it seems unsavory to treat such remains as a prop in an artwork. I put it in these harsh terms to stress a commonplace attitude toward art. As a rule artists do not make art as a form of devotion, as an expression of deeply held religious beliefs. Any artist who alludes to religiosity usually does so from the outside. Churches sometimes house reliquaries containing the bones of some saint, for example, but when an artist makes a similar object it is normally seen as ersatz – a profane facsimile at best.

What precisely Whiten’s own religious beliefs are is not clear. What can be said, however, is that he takes seriously a wide range of beliefs and mythologies across history. For example, another piece in the exhibition is titled Horus Negotiating the Waters. This consists in waxed textile formed in the shape of a boat that is suspended hammock-like at a corner of the gallery. Inside the boat sits a leather-bound human skull. According to Egyptian mythology Horus was the posthumously conceived son of Osiris, who was killed by his brother Seth. Horus was destined to grow up to avenge his father’s death by killing his uncle, who was then metamorphised into a boat. And by boat Horus journeyed into the underworld to bring his father back to the world of the living.

Horus Negotiating the Waters, 2016-2017, textiles, leather-covered human skull, 10” x 60” x 18″ (left) and detail of the inside (right)

Whiten understands the making of objects as an essentially spiritual activity, reasoning that since we are God’s creations all our work is ultimately toward a divine end (see Claude Meurehg, Art and Theology: Concerning the Spiritual in Art, 2011). As well, he alludes to prehistoric beliefs about object-making based around metallurgy. The arch-metallurgist is the divine smith, who is a shamanic figure in Iron Age societies. The smith has the divine power to hasten by means of fire the development of objects, that were believed otherwise to grow at a glacial rate in the ground. It is these sorts of beliefs, most likely, that Whiten had in mind when creating the piece titled Chasing Cobald. This takes the form of an anvil covered in shards of cobalt blue glass. Miners, in pursuit of arsenic-laced cobalt compounds used to smelt blue glass, equated this substance with mischievous goblins. (Its name derives from the German word Kobold, meaning goblin.)

Chasing Cobald, 2016-2018, glass, wood (ash, basswood, maple), found glass (crushed), 64” x 19” x 19”

Whiten is more shaman than artist. Like the divine smith, he invests his artefacts with a spiritual aura. His work couldn’t be characterised as devotional in any straightforward way, but it is certainly informed by a spiritual attitude. He is not merely intellectually curious about a wide range of mythologies, he also lives them through his work. There is, as a result, an honesty to his works. In addition, there is a wonderful poetry in his treatment of natural objects – as for example in his two Hallelujah pieces, each consisting in an object hanging from a lilac tree branch. Over all his work transcends the physical, wrapping itself in tantalising mystery.

Hallelujah II, 2015, handcrafted crystal clear glass, brass fittings, lilac branches, 60” x 84” x 19”

Hugh Alcock

Images are courtesy of the artist and Olga Korper Gallery

*Exhibition information: Tim Whiten, Suspend, January 17 – February 16, 2019, Olga Korper Gallery, 17 Morrow Ave, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat, 10 am – 6 pm.