When faced with the question about Canadian identity, I always have a tough time. What is Canada?, people ask. Coming from a small European nation, identity is an easy question. The answer has been there for hundreds and hundreds of years, born in bloody wars, proven by sacrifices. Canada, on the other hand, is a new nation, a happy one, one that has never had to face a war on its own ground. First Nations people might be able to answer the question about identity better but Canadians at large have a more challenging time. Canada is also a country where people have settled down from all over the world, bringing their own culture. So what are we, Canadians, and who are we? I look at this question as a poetical, open one, with no ready answer. Canada celebrates its 150th anniversary this year and there are many events that aim to outline our national uniqueness, exhibitions among them.

O Canada!, an exhibition in London, UK, includes 11 artists (emerging, mid-career, and established) hailing from across the country, working across a breadth of styles, technical approaches, and mediums. Intentionally circumventing any overriding theme, O Canada! finds commonalities between these artists based solely on their heritage, raising questions as to whether there truly is some sort of collective, cultural consciousness or aesthetic tradition.

Installation view of O Canada! at BEERS Gallery, London, 2017

Installation view of O Canada! at BEERS Gallery, London, 2017

Landscape is big in Canada ever since the Group of Seven, so it is not a surprise that so many contemporary Canadian artists, start as a landscapist or depicting images from nature. Canada is a beautiful land with wilderness largely present. Kim Dorland is one of those artists who is considered a landscapist and compared to Tom Thomson. He might paint landscapes but he is more like a city-boy, who brings the drama of a city into the otherwise peaceful landscape. The McMichael’s curator, Katarina Atanassova, called him a “Tom Thomson on acid” because of his vibrant, neon-like colors. His Painting method is very physical as he uses a lot of paint, in many layers, so much so that sometimes the work becomes almost sculptural (Portrait of a Landscape, Two Trees, 2017).

Kim Dorland, Portrait of a Landscape (Two Trees), 2017, oil and Inkjet on canvas, 75 x 60 cm

Kim Dorland, Portrait of a Landscape (Two Trees), 2017, oil and Inkjet on canvas, 75 x 60 cm

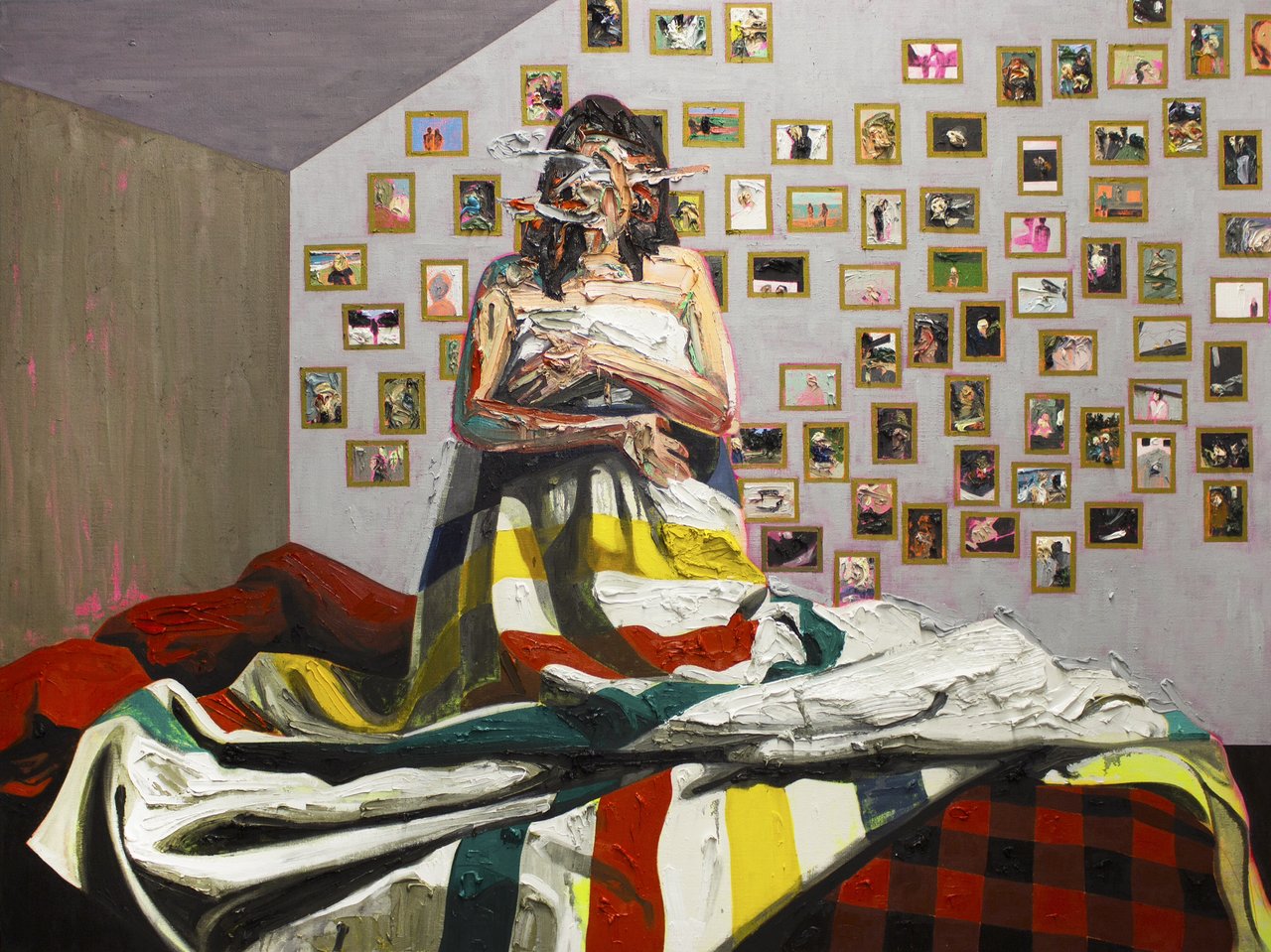

The gallery chose his painting, Bay Blanket #3 (2014) as its poster image for the exhibition. In this work, a young woman—the artist’s wife Lori—kneels on a bed in front of a wall covered with family paraphernalia, holding a Bay blanket to cover her nakedness. Her face and arms are created from thick paint that the artist has partly removed, so it looks cratered, to erase any photographic likeness. The Bay blanket is emblematic of the North and the other walls are bare, like in a cabin. Dorland’s vision of a forest, or other parts of nature, is very different from any realistic or idealistic view. He doesn’t want to be photorealistic, as he said, even in his landscapes he wants “to tell his own story.”

Kim Dorland, Bay Blanket # 3, 2014, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel, 183 x 244 cm.

Kim Dorland, Bay Blanket # 3, 2014, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel, 183 x 244 cm.

In her watercolor composition, Livable Collaborations I (2017), Andrea Williamson depicts a turtle carrying flowers on his back that are a habitat for bees, as well as corals on its legs – showing how nature’s creatures are interrelated and dependent on each other. A human finger, on the left side of the picture, is touching the creature with loving care, bringing us, humans, into the circle of nature.

Andrea Williamson, Livable Collaborations I, 2017, watercolour on paper, 50 x 40 cm

Andrea Williamson, Livable Collaborations I, 2017, watercolour on paper, 50 x 40 cm

Many of the paintings in the exhibition focus on human nature or our interactions in society. The contrasting contours and radiating lights of Erin Loree’s paintings catch our attention immediately. Her mystical compositions are abstract and somewhat realistic at the same time; I would call her method magical realism. The two figures in Sacred Time are painted with wide, energetic brushstrokes, with their earthy color rooting them into the ground. The purple stoles they wear, as well as the ribbons at the top, bridge them into mystical spheres. Together they create a temple in nature where people look toward and unite with the elements of higher realities. Loree’s pieces are charged with emotional energy and the movements grasped in time radiate light that seems to emerge from within.

Erin Loree, Sacred Time, 2017, oil and acrylic on panel, 125 x 100 cm

Erin Loree, Sacred Time, 2017, oil and acrylic on panel, 125 x 100 cm

At first sight Scott Everingham’s paintings are rigidly abstract. We focus on their captivating surfaces: the strong, textured strokes or light curtains of paint, their directions and colors, the harmony and the contrast they create. It is hard to tell what we are looking at in Laid Eyes 15; a lakeside landscape where we can enter the water through reeds, a house, a temple that is open to the sky or both. Behind the abstraction is a spontaneous but strong expression that guides us into fabricating narratives that fit the images.

Scott Everingham, Laid Eyes 15, 2017, oil on canvas, 41 x 36 cm

Scott Everingham, Laid Eyes 15, 2017, oil on canvas, 41 x 36 cm

Narrative is unmistakably the strongest element of Andy Dixon’s work. His central theme is the world of luxury and leisure. His canvases are filled with motifs of wealth: richly decorated rooms occupied by elegant lords and ladies, beauties and nudes. With those depictions, the artist could give voice to a political or social critique of the wealthy but Dixon doesn’t. He seems to enjoy that world and lately his canvases of upper class social scenes seem to feature his own previous paintings hanging on the walls in the background. He obviously borrows subject matter and stylistic elements from Matisse and Picasso, among others, creating an eclectic composition accentuated by with his use of bright colors.

Andy Dixon, Patron’s Home (London), 2017, oil and acrylic on canvas, 135 x 105 cm

Andy Dixon, Patron’s Home (London), 2017, oil and acrylic on canvas, 135 x 105 cm

In stark contrast with Dixon’s social butterflies, Justin Ogilvie’s canvases focus on the inner self. He tries to depict the metaphysical nature of the self in relation to others, their influences and interactions. Through the human figure, he addresses themes of intimacy between the bodies of lovers, strangers, and what he calls “the myriad of others within the self”. Ogilvie mixes realism and abstraction, and creates, through various mediums of painting and drawing, a magical, often metaphysical world.

Justin Ogilvie, A View for a Trip’s End, 2017, oil on linen, 91 x 76 cm

Justin Ogilvie, A View for a Trip’s End, 2017, oil on linen, 91 x 76 cm

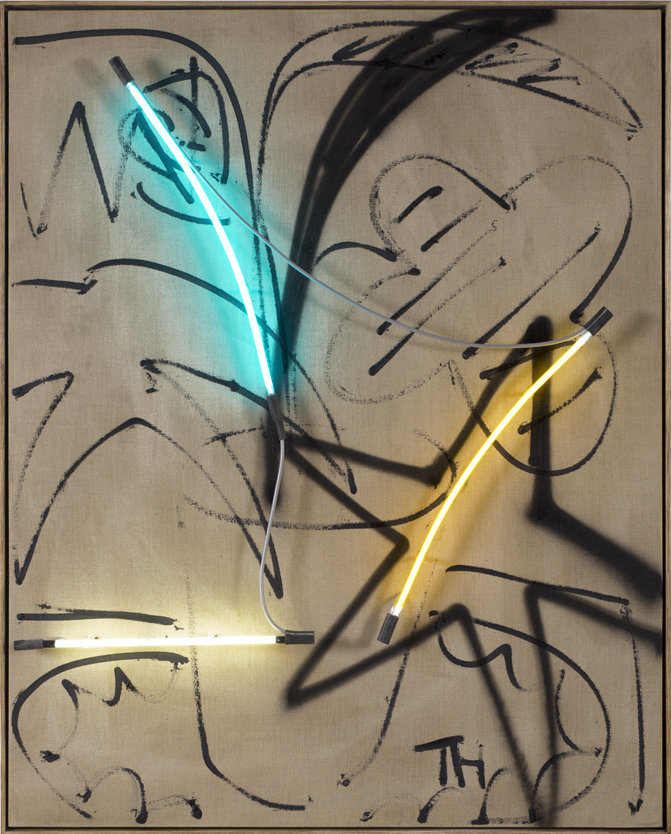

Thrush Holmes’ pieces are very different from the others in the show. His work has been described as loud, showy, playful, vulgar, larger-than-life, and yet, simultaneously delicate, detailed and subtle. Untitled 1 is a vibrant piece of the combined motifs of a feather and a star in front of a sketchy background lighted up with yellow and blue neon tubes.

Thrush Holmes, Untitled 1, 2017, oil and neon on linen, 150 x 120 cm

Thrush Holmes, Untitled 1, 2017, oil and neon on linen, 150 x 120 cm

As stated by the gallery, this exhibition is “a celebration of Canadian contemporary art internationally: asking us to consider their varied approaches and styles while offering insight into larger concepts such as land, identity, culture, and politics.” Even though the answer to Canadian identity might not be there in the gallery – it is still a wonderful way to investigate it through art.

Emese Krunák-Hajagos

Images are courtesy of BEERS Gallery

*Exhibition information: O Canada! a group show including works by Fiona Ackerman | Andy Dixon | Kim Dorland | Scott Everingham | Thrush Holmes | Erin Loree | Erik Olson | Justin Ogilvie | Andrew Salgado | Andrea Williamson | Etienne Zack, July 7 – August 19, 2017, BEERS Gallery, 1 Baldwin Street, London, UK. Gallery hours: Tue – Fri, 10 – 6, Sat – Sun, 11 – 5 pm.