The presence of phenomenological thought in artistic practice dates back to the 1960s, at a time when creative individuals were finding newer methods to fracture Abstract Expressionism’s global omnipotence. Fashioned in a post-war American society, AbEx was the nation’s cultural response to Europe’s sepulchral sociopolitical climate; one steeped in deeply rooted desolation. The rambunctious and apolitical work of de Kooning and Pollock enlivened the global consciousness to the power of painterly exposition, wherein the brush became an honest portrayal of man’s psychological impulses and were manifested in a highly gestural means of articulation. In turn, a heroic image of phallocentrism became an emblem of cultural salvation, as the candid male painter brought forth a new dawn to a fraught global artworld. However, as society progressed, and newer methods of art dispersed throughout creative circles, philosophical inquiries such as phenomenology illustrated a shift in perception away from autobiography into the realm of the viewer.

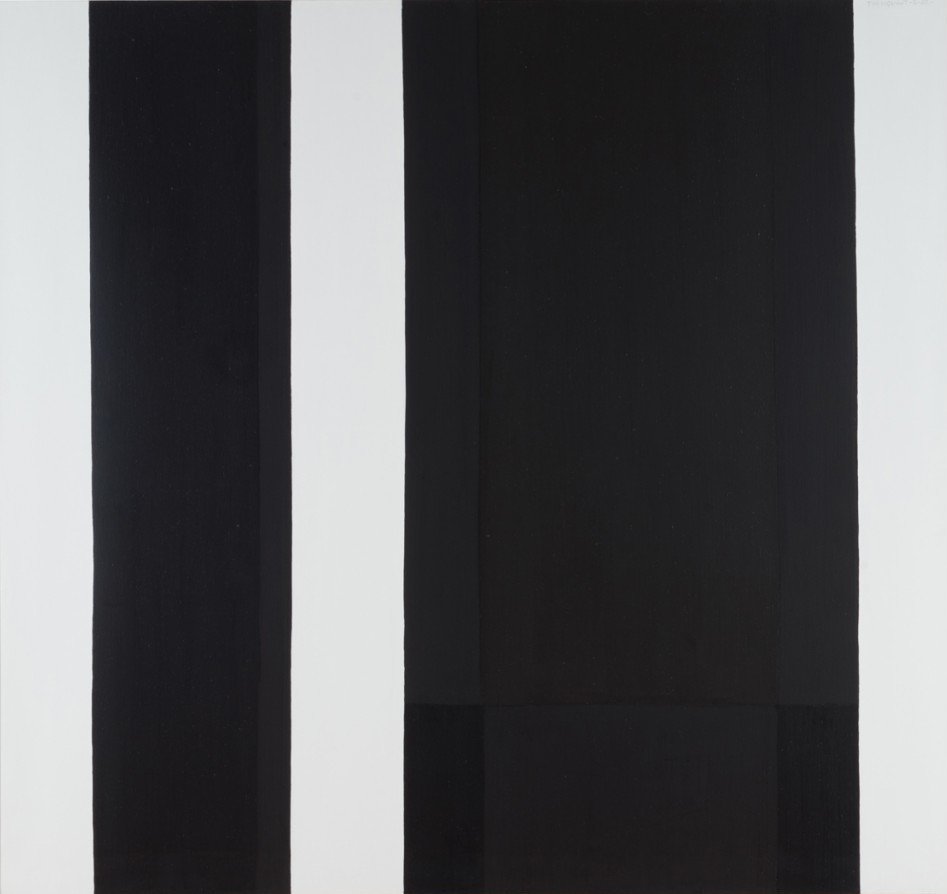

Claude Tousignant, Verticales blanches et noires, 1962, acrylic on canvas, 64″ x 68”

Claude Tousignant, Verticales blanches et noires, 1962, acrylic on canvas, 64″ x 68”

Phenomenological art, best demonstrated in the stark minimalist canon, eviscerated the confessional nature of Abstract Expressionism, reducing the presence of the artist’s brushstroke to a series of geometries devoid of subjectivity. Painting and sculpture, to artists such as Frank Stella, Donald Judd, and Sol le Wit, became a conceptual means to confront the often-rigid barriers between institution and display, audience and maker. Minimalism became a pointed reflection of a viewer’s essential and psychosomatic relationship to the plastic arts, and how these spaces for exhibition (or an artist’s subversion of it) can engender a peculiar experience for each individual. As an aesthetic manifestation of such concerns, uncomplicated shapes such as squares, rectangles, and triangles become the formalistic infrastructure for the minimalists, easily their most recognizable calling card in the visual lexicon of art history. The latest profile of Canadian painter and sculptor Claude Tousignant, on view now at Christopher Cutts Gallery, traces the artist’s lineage within the minimalist practice of autobiographical abandon.

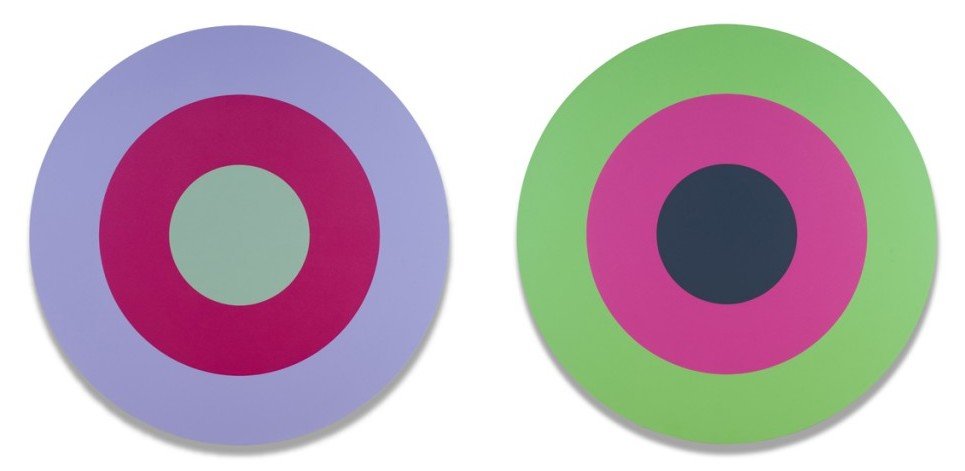

Claude Tousignant, Double cercle 66 – Cadmium chinacridone, 1975, acrylic on canvas, 66.0” each.

Claude Tousignant, Double cercle 66 – Cadmium chinacridone, 1975, acrylic on canvas, 66.0” each.

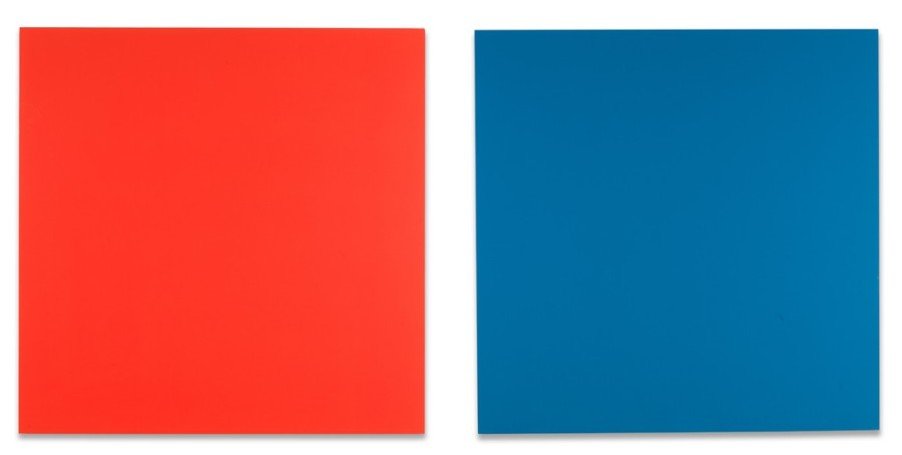

Claude Tousignant: A Selection presents a highly refined selection of his work, ranging from the glory years of the 1960s modernist movement, through to more contemporary times. What immediately becomes evident in this microcosmic exhibition is a strict aesthetic and contextual cohesiveness, illustrated by the highly ordered works on display. Five of the eight paintings are presented as diptychs, but bereft of the traditionally sacred subject matter. Each canvas is similarly monumental, scaling anywhere between seventy to well over one hundred inches in dimension, and are finished in a smooth veneer that frees Tousignant’s work from any distinct authorship into something more pure.

Claude Tousignant, Double écran chromatique en rouge et bleu, 1988, acrylic on aluminum, 48″ x 48” each

Claude Tousignant, Double écran chromatique en rouge et bleu, 1988, acrylic on aluminum, 48″ x 48” each

While Tousignant’s formal rigor may recall the likes of Frank Stella and Ellsworth Kelly, the artist’s thematic fixations remain similarly beyond any historical epoch. These contemplative and phenomenological expressions exist beyond sociopolitical benefactors, as they aim to tackle concerns that are distinct to human existence and the confluence of art and objects within that. This exhibition is an affirmation of Tousignant’s dedication to his practice, and how untethered from time and situation his work remains.

Claude Tousignant, Bleu-rouge / Vert-violet or #7-80-84, 1980, acrylic on canvas, 84” each

Claude Tousignant, Bleu-rouge / Vert-violet or #7-80-84, 1980, acrylic on canvas, 84” each

David Saric

Images are courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery

*Exhibition information: April 29 – June 10, 2017, Christopher Cutts Gallery, 21 Morrow Avenue, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat 10 am – 6 pm.