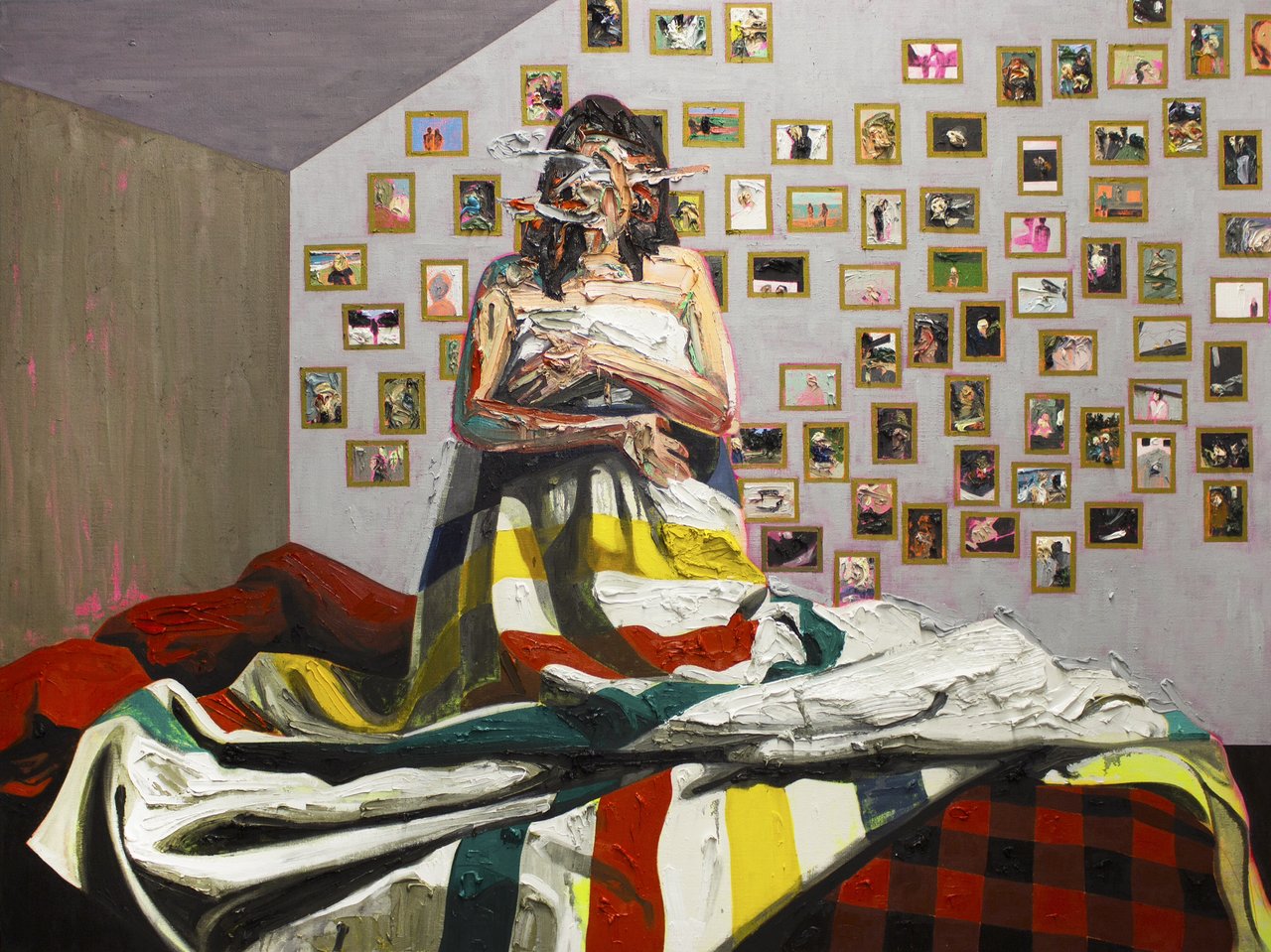

The first Kim Dorland painting I really liked was Bay Blanket #3 in his 2014 exhibition at Angell Gallery. In this work, a young woman—the artist’s wife Lori—kneels on a bed in front of a wall covered with family paraphernalia, holding a Bay blanket to cover her nakedness. Her face and arms are created from thick paint that the artist has partly removed, so it looks cratered. There are heavy patches of paint on the blanket as well as the images on the wall. It is very physical, very energetic, and you can see the movements of the artist’s hand throughout as he layered and manipulated the paint. Somehow it is still able to capture that intimate moment, as the figure hugs her body and looks out from her surroundings. The Bay blanket is emblematic of the North and the other walls are bare, like in a cabin.

Kim Dorland, Bay Blanket 3, 2014, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel, 72 x 96 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Bay Blanket 3, 2014, oil and acrylic on linen over wood panel, 72 x 96 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Another, a smaller Bay Blanket, hung in a corner of the Angell Gallery with a cordon around it, warning viewers not to touch it because of wet paint. I’ve seen that kind of sign before for another artist but learned that it was often used for Dorland’s work as he uses an lot of paint, in many layers, so much so that sometimes the work becomes almost sculptural.

Dorland is considered a landscape painter. Landscape is big in Canada since the Group of Seven, and many collectors here focus on them. It is not a surprise that Dorland, like many other contemporary Canadian artists, started as a landscapist, but he is more of a city boy. Coming from a tough background in east-central Alberta, he left his mother at the age of 16 and moved into his girlfriend’s (now his wife) Lori Seymour’s home. He described himself then as a “going nowhere teen.” He had no vision of the future, not even a single idea, until he opened a book about Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. Thumbing through the book he felt enlightened. He found what he wanted. He found art. After that discovery he went to Emily Carr University of Art + Design and York University.

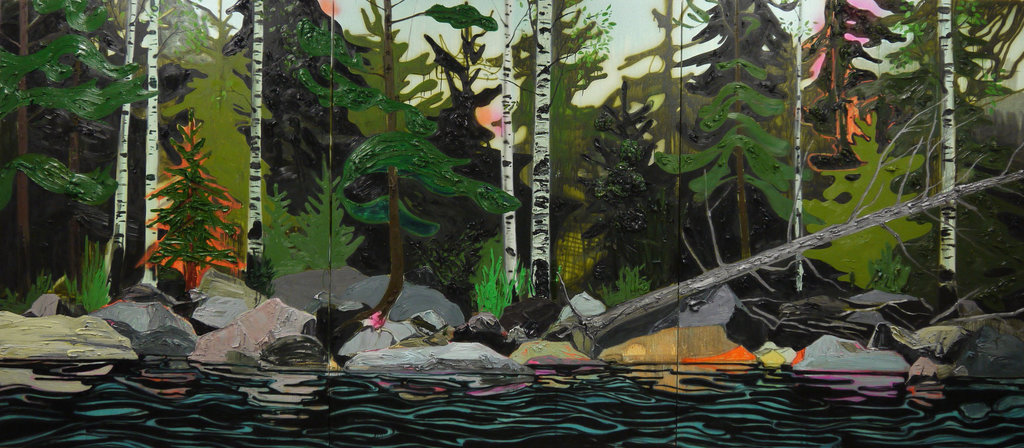

Tom Thomson is still one of his favourites. They share the same hermit-like attitude and Dorland is mostly in his studio “lab” in Toronto. Their painterly roads crossed, when McMichael’s chief curator, Katerina Atanassova invited Dorland to become artist-in-residence and to visit the places Thomson did, as well as look at his work in the museum. Dorland was hesitant at first, as he said, “If you through me in a canoe, handed me an axe and told me to survive, I’d be dead pretty quickly.” But he agreed, and paddled into Algonquin Park where he felt the spirit of the land, a “supernatural air.” The result was the exhibition titled You Are Here: Kim Dorland and the Return of Painting. 90 freshly painted canvases of Kim Dorland were exhibited with 38 Thomson sketches as well as works by Emily Carr, David Milne and members of the Group of Seven. Dorland’s paintings were mainly landscapes, some of them even rethinking Thomson sketches, like Woodland Waterfall (After Tom Thomson). The star of the show was French River, a very large triptych, showing Dorland at his best as a traditional landscape painter.

Kim Dorland, French River, 2013, acrylic on jule on wood panels, 96 x 216 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Kim Dorland, French River, 2013, acrylic on jule on wood panels, 96 x 216 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

People compared him to Tom Thomson, Atanassova called him a “Tom Thomson on acid” because of his vibrant, neon-like colors. It doesn’t matter how much Dorland admires Thomson, there are more differences than similarities in their work. First and foremost, Dorland is not an outdoor man like Thomson, but a city dweller. He might paint forests, lakes, hills, trees, sky, campsites and animals – but he is an outsider in nature. “My identity as an outdoor man is not part of my practice.” – he said to James Adams of The Globe and Mail – “My work is really about the perfect psychological moment. Sometimes that moment is in nature. Sometimes it’s in my living room.” He may paint landscapes, but he’s painted them in his own way. Thomson found drama in nature; Dorland brought drama into nature. His vision of a forest, or other parts of nature, is very different from any realistic or idealistic view. Even in his landscapes he wants “to tell his own story.”

There are some returning motifs in Dorland’s oeuvre. The first painting he sees as his “own”, a turning point in his career, is The Loner, from 2005. It depicts a young guy, half hiding behind a tree, holding a plastic bag. He looks like a teenager escaping from the nearby city for some quietness or who knows what mischief. The trees are stylized, showing their outlines only and with a few patchy details, like falling off bark – almost abstract, like all the other trees in his paintings. The trees on Fuck Love (2008) are truly hurt; their trunks are covered with carvings of letters and messages, with spray paint and something that looks like asphalt. These images of the city’s cat-piss-smelling, graffiti-covered alleyways are creeping into the forest. All the supposedly happy butterflies seem fake here and the dirt dominates. Then, in his latest show, I Know that I Know Nothing (Angell Gallery, 2016 October), All Work and No Play …2 (2016) the dead tree trunks in a pine forest are covered with skulls and images that might be left behind by a zombie-walk of sick-minded teenagers.

Kim Dorland, Fuck Love, 2008, oil, acrylic and spraypaint on wood, 72 x 96inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Fuck Love, 2008, oil, acrylic and spraypaint on wood, 72 x 96inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

We associate landscapes with nature, beauty and the freedom of the outdoors. Landscapes represent creation as well and are supposed to be welcoming. Not so in most of Dorland’s paintings. Here You Are, (2013) a self-portrait of the artist, depicts him standing in front of his easel, surrounded by dark trees. It looks like a nightscape but the light coming through between the trees suggests otherwise. Most of the surface is covered with heavily textured black paint, only the canvas and easel shines with pink. This is not a welcoming forest, but a forest like Hansel and Gretel’s from the Brothers Grimm tale—a forest of nightmares that threatens to swallow the intruder. Darkness surrounds the artist and he might easily disappear into it. Only the creation of the painting, a canvas-within-a-canvas, give us some hope. It makes you wonder if the artist is aware of the dangers or totally absorbed in his activity or maybe doesn’t care at all.

Kim Dorland, Unitled , 2013, oill on just over wood panel, 20 x 16 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Unitled , 2013, oill on just over wood panel, 20 x 16 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

In most of Dorland’s landscapes the trees are bare, the sky is purple, the sun is blinding or darkness covers everything. The trunks of trees are covered with ugly carvings of skulls and zombie heads. Even the small bridge over a spring is spray-painted with graffiti. As in Dorland’s 2015 show, I’ve seen the future, Brother, the city with its aggressive decoration seems to invade nature. Will this be the future? I hope not, and note his message on the bridge: Go Back.

Kim Dorland, Go Back, 2015, oil and acrylic on linen over panel, 60 x 72 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Go Back, 2015, oil and acrylic on linen over panel, 60 x 72 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery.

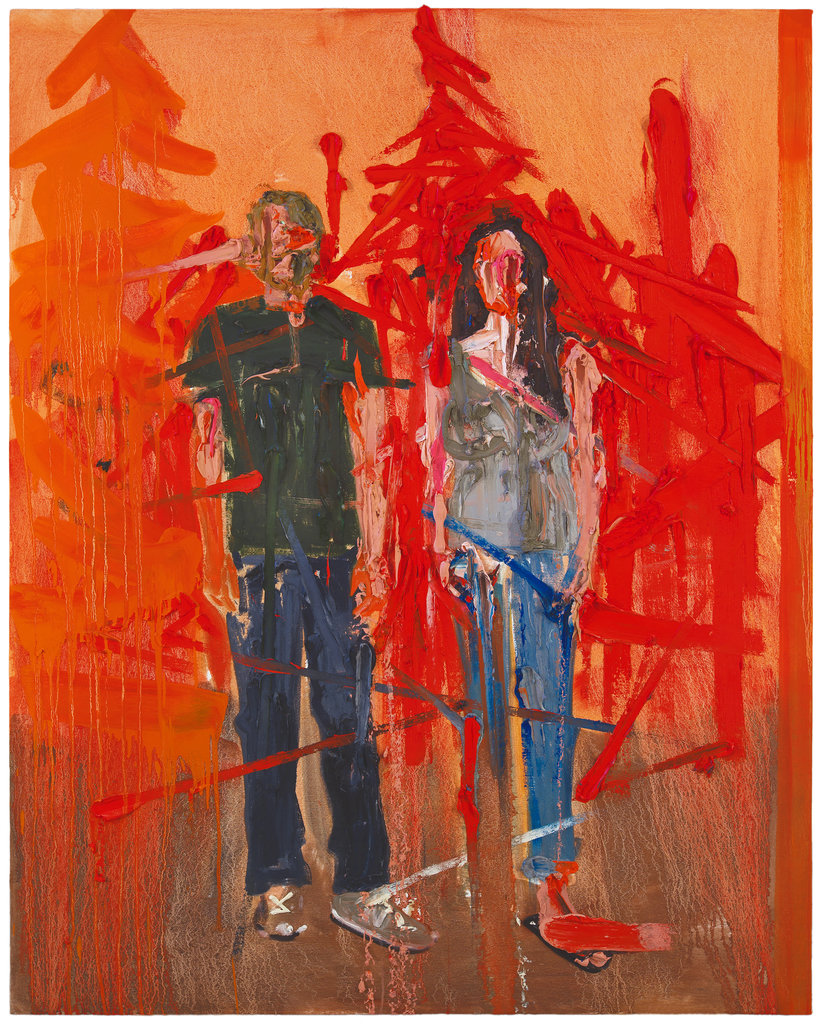

Dorland is also considered a portraitist, including self-portraits, double portraits with his wife Lori and his painting series of Lori. All his portraits are faceless. In the age of a hundred selfies a day this seems strange. Why is that? “I literally just started piling on the paint because I wanted to remind the viewer that they are not photographs; they’re paintings.”, he explained. In Here You Are, his back is to us, and in Self-portrait at 38, (2012) his blood-red face is scratched until it’s unrecognizable. In the double portrait, Grown-ups, (2012) red dominates again and only the posture of the couple suggests what being an adult means. The brightness doesn’t mean happiness; a sense of loneliness and melancholia radiates from the painting.

Kim Dorland, Grown-ups, 2012, oil on linen, 60 x 48inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Kim Dorland, Grown-ups, 2012, oil on linen, 60 x 48inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Dorland has painted his wife and muse Lori throughout his entire career, even dedicating some exhibitions completely to her: For Lori, (2011 at Mike Weiss Gallery, New York) and his latest show I Know that I Know Nothing (2016 at Angell Gallery, Toronto) where the larger room was filled with images of her. Dorland painted these images more from memory than for creating memories. They are not traditional “love” paintings. There is certainly some intimacy in them. Sometimes Lori looks vulnerable in her posture, as in Yellow Dress, (2007) when she kneels in a nice summer landscape. She is all over Dorland’s canvases; enjoying the cool water at Emma Lake, in a dark forest, walking and disappearing into the night sky (The Girl Disappears, 2010), a ghost, a vision—real and imagined.

Kim Dorland, Yellow Dress, 2007, oil and acrylic on canvas, 44 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Kim Dorland, Yellow Dress, 2007, oil and acrylic on canvas, 44 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

But Dorland does “not shy away from the brutality of love” either, as Allison Meier stated in her review in Hyperallergic (For Lori, Mike Weiss Gallery, 2010). Lori swims in a night lake where her body is blood red, surrounded with black and deep purple rivulets, like dried blood, seemingly swimming in dangerous waters (Night Swimming, 2013). In some other, darker, portraits her face appears like a skull and even the paper is ripped.

Kim Dorland, Night Swimming, 2013, oil and acrylic on wood panel, 11 x 14 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Kim Dorland, Night Swimming, 2013, oil and acrylic on wood panel, 11 x 14 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

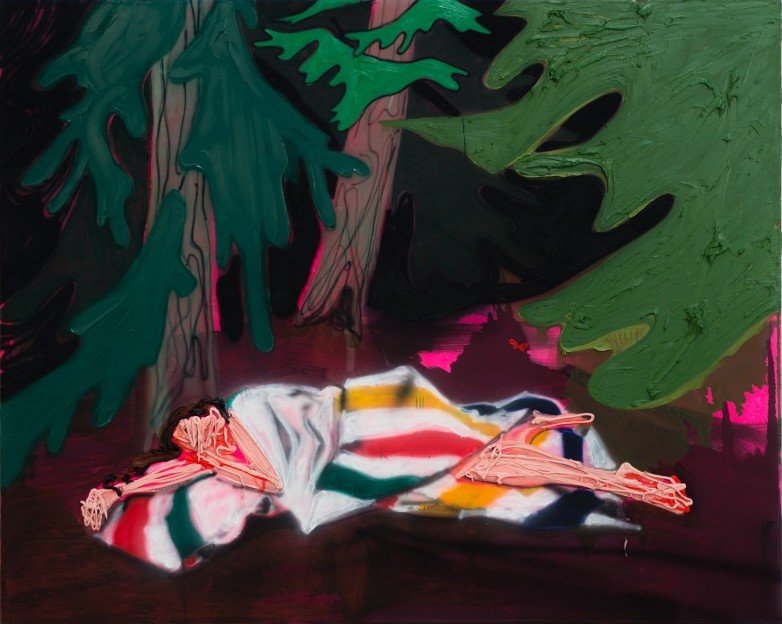

Still, Dorland’s vision of Lori is not always that dark. Last visit, (2013) or After the Party, (2014) depict some nice moments from his family life. Lori’s beauty shines in his 2016 show, as she relaxes under trees on that Bay blanket (Rest) or while admiring her image in a peaceful lake (Untitled, Lori on purple, 2016). It seems that some harmony has been found.

Kim Dorland, Rest, 2016, oil on polyester, 48 x 60 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Kim Dorland, Rest, 2016, oil on polyester, 48 x 60 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Dorland pushes the limits of his media. He paints very physically. His strokes are sometimes even brutal and he uses an abundance of paint, layers upon layers, until it’s so heavy and textural that it looks like colored clay and might fall away from the canvas. To prevent that he uses screws to keep it in place. Within the layers of oil and acrylic paint he incorporates different materials such as wood, strings, fur, feathers, glitter and enhances the outcome with glow-in-the-dark pigments. His paintings are impossible to dismiss. When the surprise of his technique fades away, a deeper meaning emerges as Dorland wants to engage in a psychological dialog with the viewer.

Emese Krunák-Hajagos