Writing about Edward Byrtynsky’s 2005 China project, philosopher and critic Mark Kingwell notes the contrast between the photographs of that period and Burtynsky’s earlier works, such as the 1999 Oxford Tire Pile #1, Westley, California (“The Truth in Photographs: Edward Burtynsky’s Revelations of Excess”, in Opening Gambits: Essays on Art and Philosophy). Although similar in subject matter to the later works, Burtynsky’s earlier photographs are picturesque, “painterly” in their traditional approach to composition; even when depicting landfills heaped with industrial waste, they seem to teeter “between pure aesthetic formalism” and the “informative realistic end of photojournalism.” This wavering, Kingwell notes, inevitably prompts a question of artistic responsibility: is it permissible to present ethically problematic things as aesthetically attractive? The question, formulated in this way, is misguided, argues Kingwell rightly; the work’s responsibility lies to the world it creates, not to the world in purportedly depicts. But repetition opens doors; so, brought up time and again, the question of responsibility begins affecting the artist’s further choices. The emphasis of the 2005 China is clearly titled towards the ethical side of its subject matter: industrial development, rapid, violent, and oblivious to its ruinous impact on human life and nature. In adopting this emphasis, Burtynsky, in Kingwell’s words, “throws his environmental-activist cards on the table,” perhaps, as Kingwell thinks, intensifying the viewer’s experience, perhaps, as it seems to your correspondent, blowing up the delicate balance so carefully constructed and maintained in his previous works.

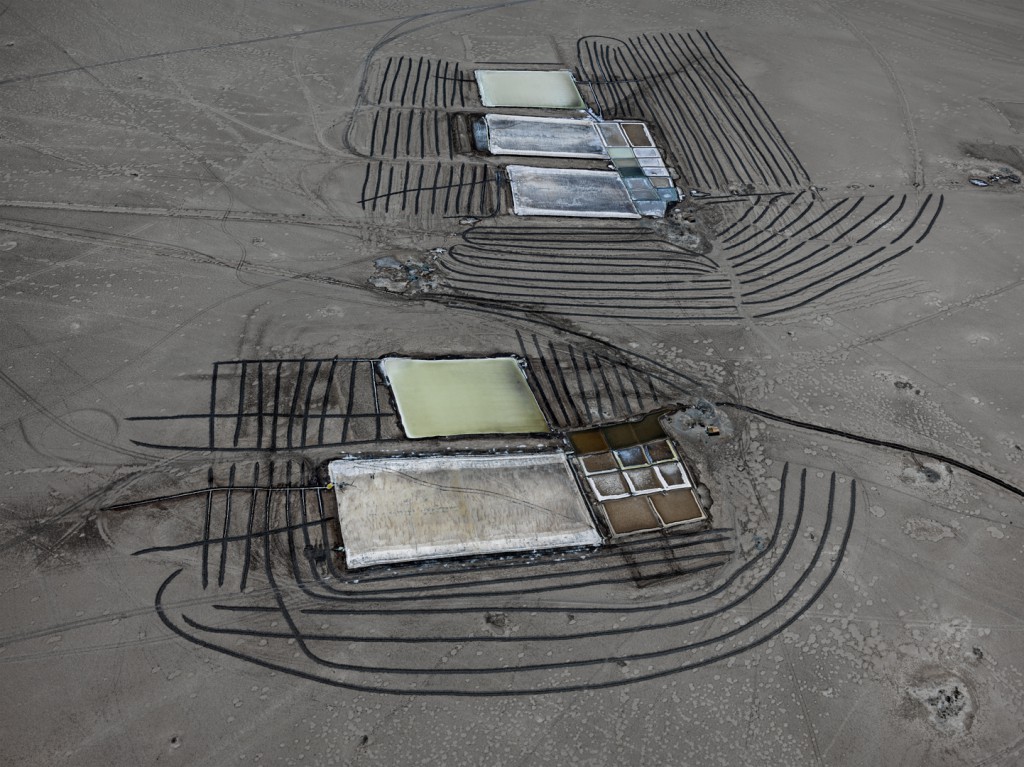

Edward Burtynsky, Salt Pan #29, Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India, 2016, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Edward Burtynsky, Salt Pan #29, Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India, 2016, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Well, all you aesthetes and art-lovers concerned with moralization of contemporary art, you may sigh with relief now, as Byrtynsky’s new exhibition puts him back on track to the paradise of beauty and artistry. With reservations, of course; thematically, Salt Pans is continuous with works of the previous decades, although the disorderly, coarsely drawn polygonal salt pans of the Little Rann of Kutch in Gujarat, India hardly convey the mood of environmental apocalypse or disregard for humanity to the same extent as, for example, the tires of the 1999 Oxford Pile or the rows of uniformed factory workers in 2005’s Manufacturing #17. There might be some other, less salient, story of decay or neglect behind these shapes, lacklustre yet neither gloomy nor sullen; the salt pans, the exhibition catalogue says, are under threat for reasons both environmental and economic, and so is the workers’ traditional way of life, undetectable as it is from the images’ topographical perspective.

Edward Burtynsky, Salt Pan #15, Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India, 2016, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Edward Burtynsky, Salt Pan #15, Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India, 2016, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

But to focus on that would be to ignore what makes this exhibition so artistically successful. Salt Pans are almost unabashedly non-ethical, but in ways more interesting than Burtynsky’s 1990s phase. If the earlier workers secured the viewer’s appreciation by the tried and true (not to say hackneyed) methods such as golden section or disappearing perspective, these ones speak to those with background in modernist and contemporary art, suggesting references to classical Futurist and Abstractionist paintings. Kernels of that meta-artistic referentiality are already found in Burtynsky’s earlier works, shown today as part of the sister retrospective exhibition, Essential Elements. For example, circles and lines of Silver Lake Operations #16, Lake Lefroy, Western Australia, bear resemblance to Wassily Kandinsky’s Red Circle, 1939. Salt Pans develop tendency by presenting what often resembles the abstract, dada-informed painting such as Paul Klee’s the 1919’s Falling Bird or the 1930’s North German City. Irony, not activist indignation, permeates Salt Pans, are they look like belated, and self-consciously superfluous, justifications of the representational capacities of abstract art. The photographs’ ethical background literally disappears into the background, indeed gray and gloomy, in contrast to the foregrounded forms, with their casual lines and comical splashes.

Edward Burtynsky, Silver Lake Operations #16, Lake Lefroy, Western Australia, 2007, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Edward Burtynsky, Silver Lake Operations #16, Lake Lefroy, Western Australia, 2007, chromogenic print. Courtesy of Nicholas Metivier Gallery

The result of the ambiguity of Burtynsky’s 1990s works, notes Kingwell, is that they seem to maintain a delicate balance between the beautiful and the troubling only when showcased in a gallery; when placed on the wall in a commercial setting (as, apparently, they are in Pearson Airport’s business class lounge), they come dangerously close to celebrating the devastation they depict. I suspect that nothing of the sort would happen to the ethically charged 2000s works; a Shanghai airport would not put them on its walls. But the solution was more troubling than the problem itself; China and other works of that period would not be wrongly interpreted outside of the gallery context because no one would dare take them out of it. One may say that Salt Pans finds a way to bring Burtynsky’s photographs back into the world. In a gallery, these images look almost too artistic, their reference directed inside the art world, not outside of it. But, taken outside, they would, perhaps, introduce both artistry and ethics into a lay location, even if they end up decorating another airport lounge, hanging by the rows of complimentary tablets, reminding a chance traveller (laptop, suit and tie, bloodshot eyes) of a long forgotten visit to a painting gallery while conveying a vague sense of there being something wrong in the world of disappearing panting-like salt pans.

by Andriy Bilenkyy

*Exhibition information: September 29 – October 22, 2016, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, 451 King Street West, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat, 10 am – 6 pm.