How do you reintroduce Canada’s most famous artist to a Canadian audience? If that artist is Lawren Harris, and the show is titled The Idea of North, then the groundwork seems already laid—reframe Harris’s paintings of the great white north as idealized yet problematic, taking into consideration factors of race, class, gender, and privilege that informed his work. After all, a basic hanging of Harris’s landscape paintings is nothing new. So with this potential its fingertips, did the show get as critical as it could have?

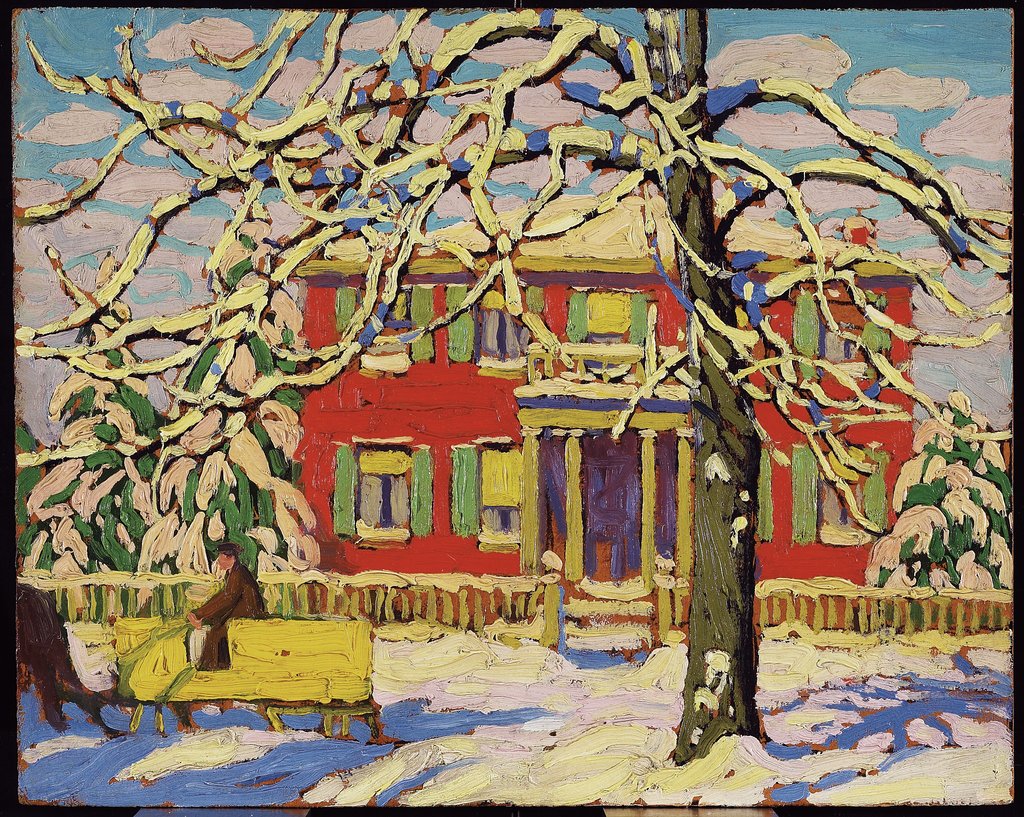

Lawren S. Harris, Red House and Yellow Sleigh, 1919, oil on pulpboard, 26.7 x 33.7 cm. Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ontario

Lawren S. Harris, Red House and Yellow Sleigh, 1919, oil on pulpboard, 26.7 x 33.7 cm. Courtesy of Art Gallery of Ontario

With help from co-curator Andrew Hunter—who, for the AGO’s iteration of the show, added two new sections on old Toronto’s Ward neighbourhood, a source of inspiration for Harris—the show lightly addresses these critical issues, but is perhaps too polite in its approach. In the exhibition’s core where iconic mountain peaks and icebergs hang, didactic panels softly explain that “Harris did not usually include [in his paintings] the people he met—either Inuit or southerners working in the Arctic,” because this was his “highly personal response to place.” These panels acknowledge that Harris left people out of his paintings on purpose, but they avoid talking critically about the artist’s privileged background as, for lack of a nuanced term, a wealthy white male, and how this erasure—notably of Indigenous communities—brings up questions of power relations at play.

Lawren S. Harris, Icebergs, Davis Strait, 1930, oil on canvas, 121.9 x 152.4 cm. Courtesy of McMichael Canadian Art Collection

Lawren S. Harris, Icebergs, Davis Strait, 1930, oil on canvas, 121.9 x 152.4 cm. Courtesy of McMichael Canadian Art Collection

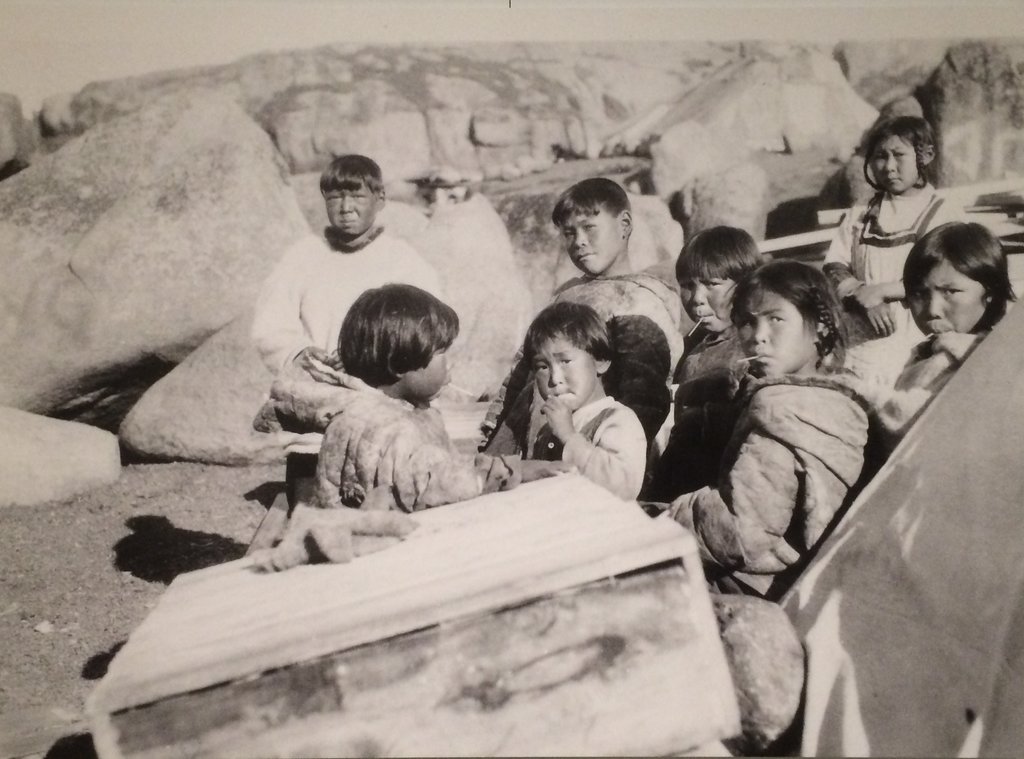

Honourably, the curators try to rectify Harris’s dismissal of the Inuit specifically by including two large-scale photographic reproductions of Inuit families, taken by Harris himself in 1930. They hang amongst barren iceberg paintings and depictions of Baffin Island’s empty North Shore, and the juxtaposition is certainly charged: not only is it proof that Harris encountered these communities, but also blatant evidence of his conscious painterly disregard.

Lawren S. Harris, Inuit Children, Pangnirtung, Baffin Island, 1930, reproduction from original photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Lawren S. Harris

Lawren S. Harris, Inuit Children, Pangnirtung, Baffin Island, 1930, reproduction from original photograph. Courtesy of the Estate of Lawren S. Harris

However, without including an Indigenous voice in this section of the show, the curators’ attempt at rectification falls short. A didactic panel admits that “Unfortunately, the power of Harris’s vision has led many to imagine the Arctic as an empty and unpopulated land,” so why not incorporate an Indigenous voice or narrative in response to this point?

Installation view from The Idea of North. Photo: Emily Lawrence

Installation view from The Idea of North. Photo: Emily Lawrence

Elsewhere in the show, contemporary artist Anique Jordan was commissioned to create two photographic works in response to Harris, wherein she addresses the Black communities active in The Ward in the early 1900s—a community unsurprisingly absent from Harris’s paintings of the neighbourhood. Jordan’s works are probably the most powerful in the show: featuring the voice of a young black female juxtaposed alongside Harris’s expresses a point about erasure that didactic panels simply can’t. Incorporating something similar by an Indigenous artist into the core section of the show had the potential to cultivate further critical dialogue.

Anique Jordan, Mas’ at 94 Chestnut, 2016, chromogenic print. Courtesy of the artist

Anique Jordan, Mas’ at 94 Chestnut, 2016, chromogenic print. Courtesy of the artist

Thus, The Idea of North merely scratches the critical surface. The show seems aware of the problematic aspects of Harris, but is overly polite in its explanations and is seemingly too timid to push further—perhaps in fear of appearing blasphemous against one of Canada’s most famous artists.

Emily Lawrence

*Exhibition information: July 1 – September 18, 2016, Art Gallery of Ontario, 317 Dundas Street West, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tue & Thur, 10 am – 5 pm; Wed & Fri, 10 am – 9 pm; Sat & Sun, 10:30 am – 5:30 pm.