The tagline for the Tattoos exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) Ritual Identity Obsession Art is a perfectly succinct outline for the cross-examination of tattoo practices across continents and through history. Most of the objects are treated like artifacts and documentation, but all seem included for the purpose of elevating contemporary tattoo practices and styles to an art form. In addition to the various two and three-dimensional documents, thirty-three master tattoo artists were commissioned to produce large Japanese bodysuit style drawings or works on silicone manikins. Each featured artist is accompanied by a narrative including where they apprenticed, when they began, where they’ve worked or traveled, what their style is called, and whether or not they have other practices. In this exhibition, tattoos are treated as a new branch of art history.

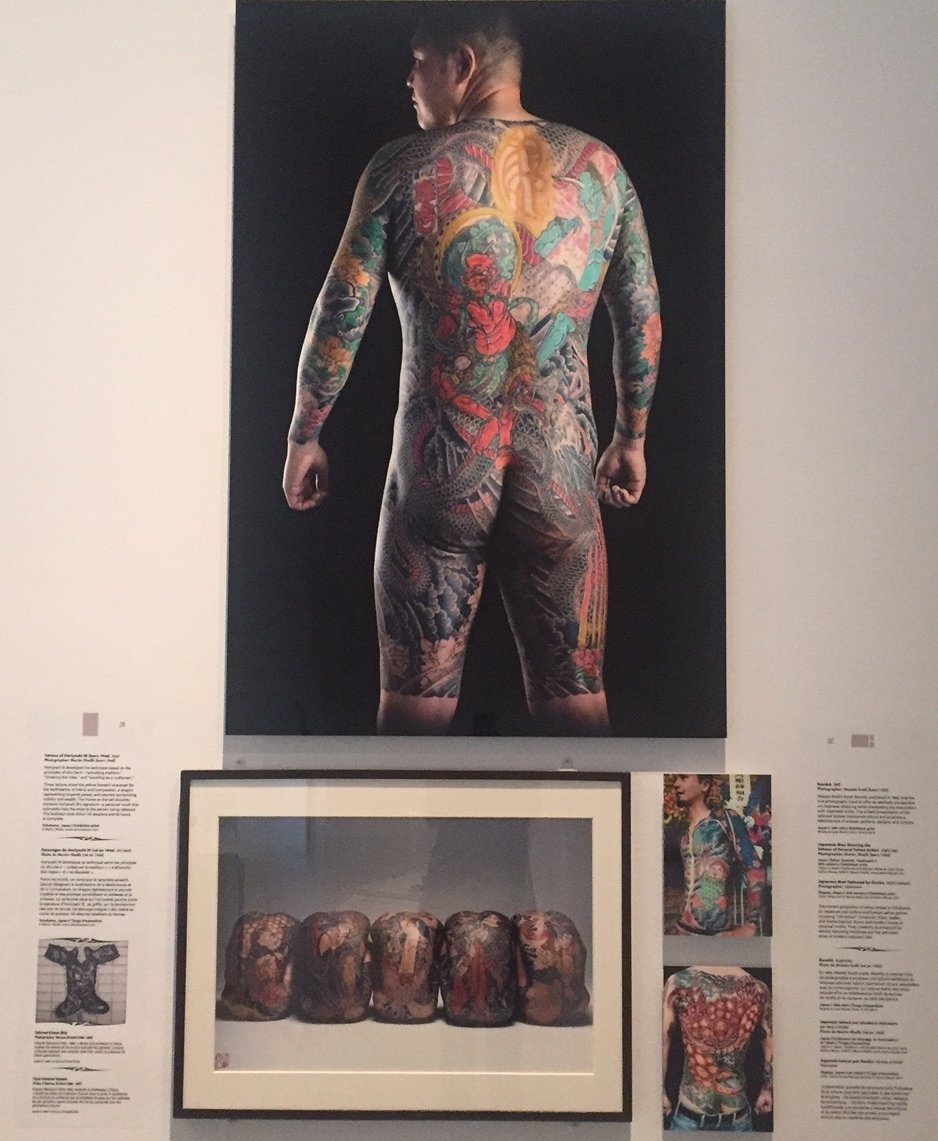

Japanese bodysuit style tattoos

Japanese bodysuit style tattoos

Most of the exhibition is laid out by country or region including North America, Europe, New Zealand, Samoa, Japan, Eastern Polynesia, Philippines, Borneo, Indonesia, Thailand, China and several Latino cultures. In each section, the historical narrative builds towards the eventual acceptance of contemporary tattoo culture. In other sections unassigned to a country, historical cross-cultural stigmas are explored. Some of these stigmas include gang symbols, prison rank markings, initiation rights, marks of punishment or ownership by pimps or Nazis, signs of marital status or motherhood, and membership to a side show act or team of sailors. Other, more contemporary reasons for having tattoos are expressed as the need for individualism and to re-establish traditional culture and symbols. In the early 20th century the Western world developed another vague stigma against the tattoo as a practice only worn by wild, ‘uncultured’ tribes. Adolf Loos perpetuated this through even the development of unadorned architecture. And again a force from the Western world, missionary and other religious activity nearly eradicated tattooing practices until recent contemporary resurgence.

![]() Silicone Manikines with ‘Tribal’ tattoos

Silicone Manikines with ‘Tribal’ tattoos

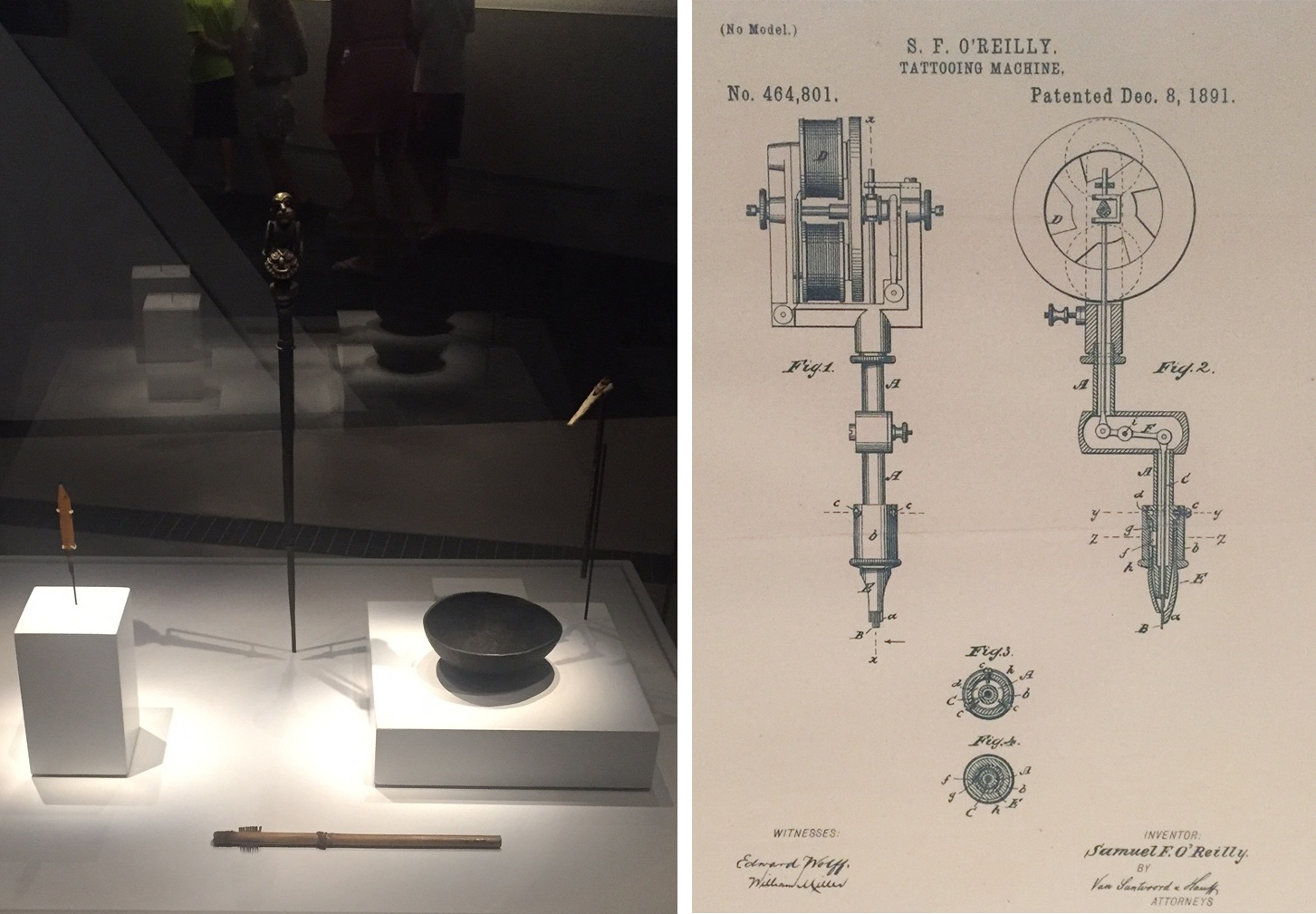

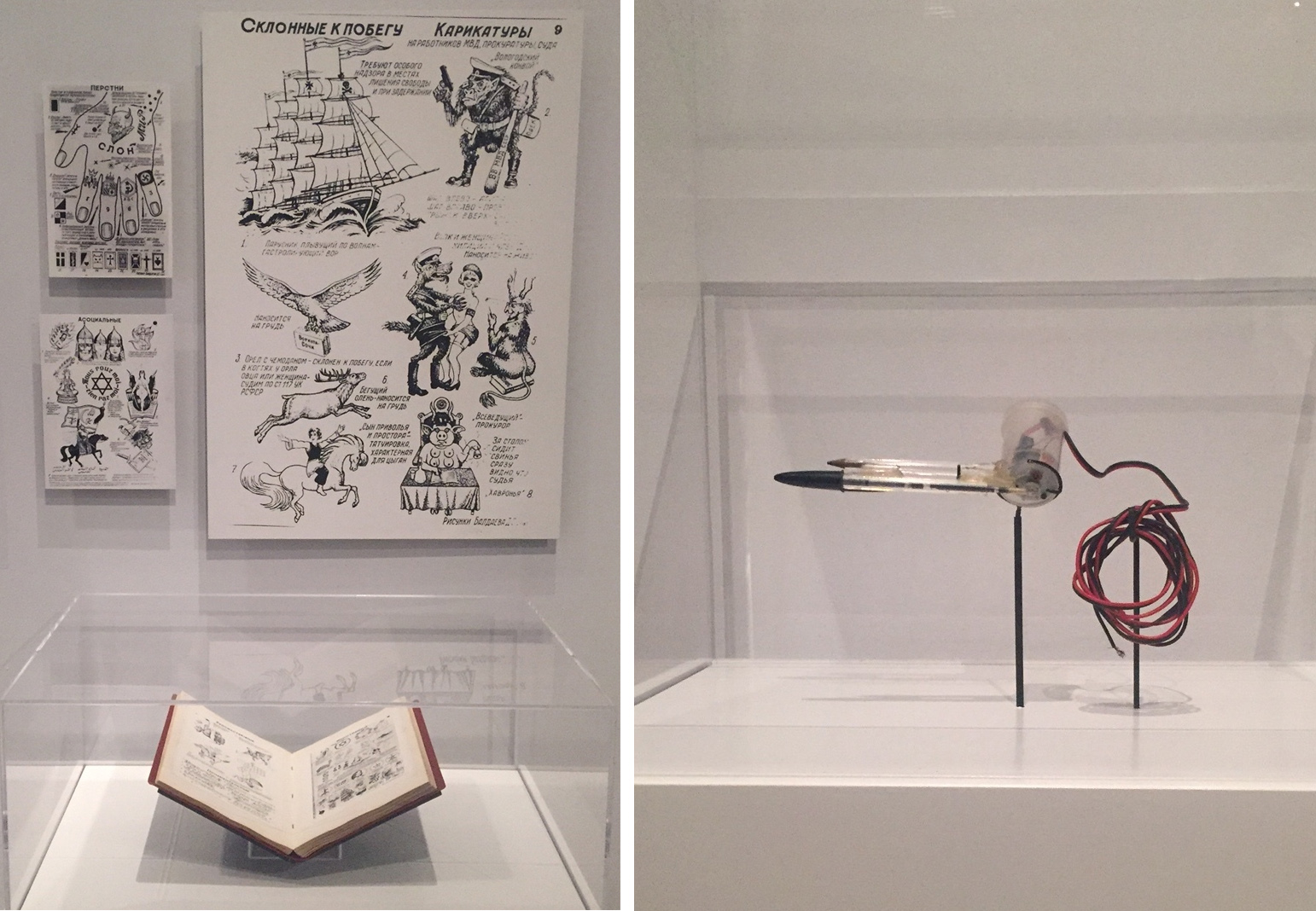

Some of the symbols and styles evolved due to the technology available. Technological tattoo history included in the ROM’s display begins with wooden rods and combs from the 19th century, ink bowls from the early 20th century, and manuscripts with drawings of symbols. Most of these tools were used to make ‘tribal’ tattoos with larger, thicker lines and dots. The advent of the electric tattoo machine by Milton Zeis was an evolution of Thomas Edison’s Electric Stencil Pen, which produced 3000 punctures per minute. Finer or more accurate lines and more saturated colours that are quintessential to contemporary tattoo styles have developed from the electric gun. Another, even more ingenious tattoo gun on display is made of wire, spool and a ballpoint pen, conceived of and used in prison.

Late 19th Century Tattoo kits (left) and Diagram for electric tattoo gun (right)

Late 19th Century Tattoo kits (left) and Diagram for electric tattoo gun (right)

Prison Tattoo symbolic guide (left) and Prison Tattoo Gun (right)

Prison Tattoo symbolic guide (left) and Prison Tattoo Gun (right)

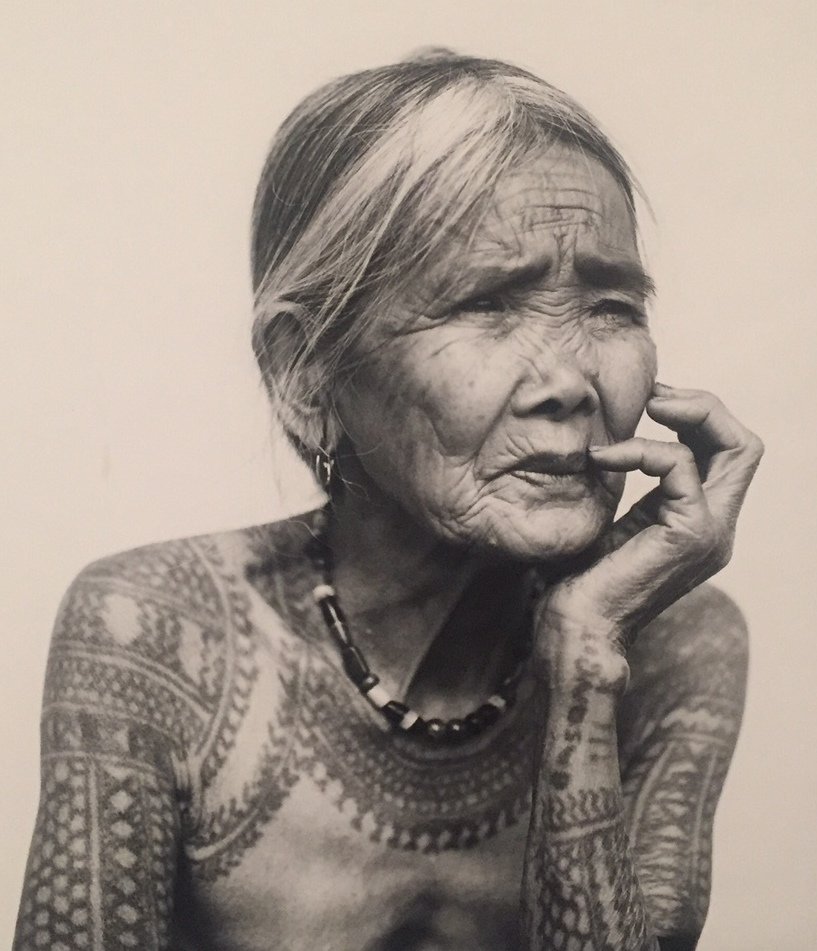

Among the dozens of artists mentioned, some stood out for their dedication and style. One of the last Kalinga master tattooists from the Philippines, Fang-od Oggay (born 1920) is featured as an artist using traditional tools and styles. The contemporary British artist Xed LeHead, on the other hand, submitted a silicone arm covered entirely in ultraviolet light sensitive ink forming thick, geometric patterns. With each photograph, a photographer who specializes in tattoos is listed alongside the featured tattoo artist. Tattooed people have long been the subjects of the photographic, voyeuristic gaze as representative of native or sub-cultures.

Photographer Zoe Forget, tattoos by Guy Le Tatooer (left), and Jean-Luc Navette (right)

Photographer Zoe Forget, tattoos by Guy Le Tatooer (left), and Jean-Luc Navette (right)

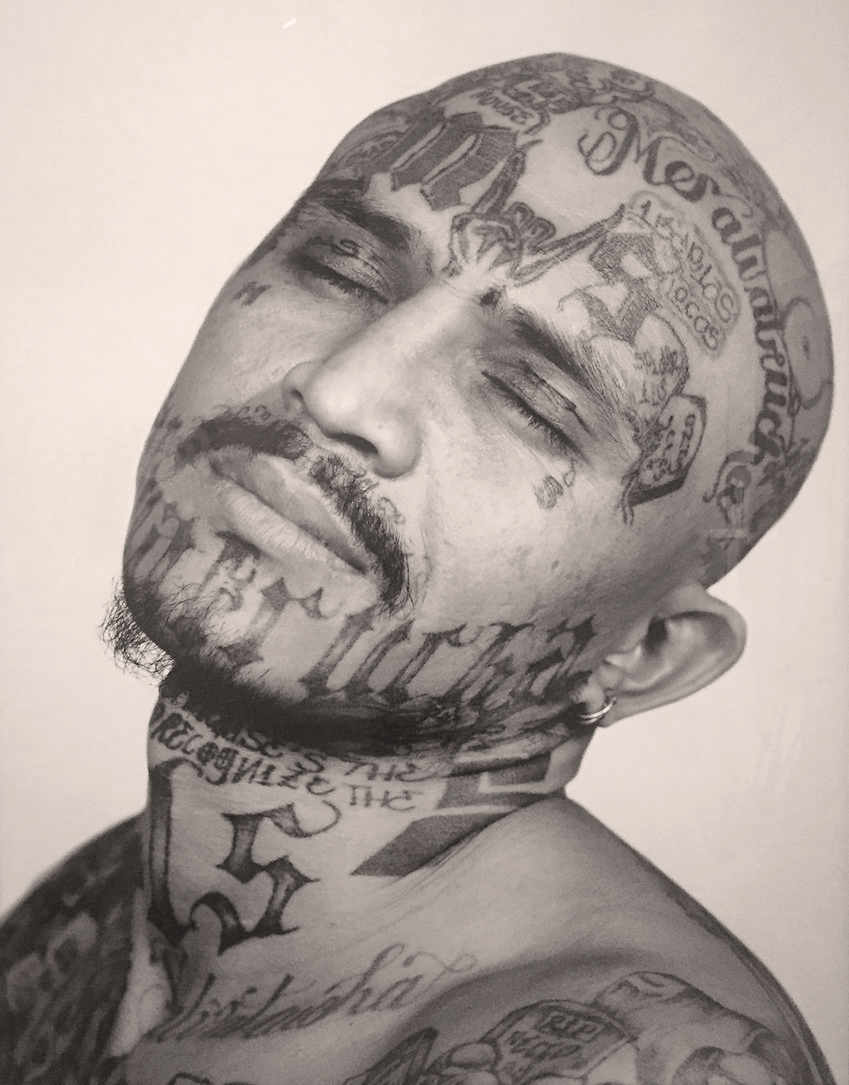

More recently, the acceptance of tattoos has made photographs of tattoos artworks like the tattooed bodies that are their subjects – as opposed to documentation. One beautiful series of portraits titled “Series Maras” by Isabel Muñoz is large-scale black and white documentation of the three weeks she spent in El Salvador prisons. The gang members she chose to photograph have offensive tattoos that perpetuate violent and anti-social behavior while their postures and facial expressions communicate vulnerability.

Isabel Muñoz, Portrait from Series Maras

Isabel Muñoz, Portrait from Series Maras

There are many artworks in the Tattoo exhibition, however, displayed alongside artifacts, they serve more as supportive documentation. Portraits of tattooed people validate tattoos as an artistic medium and elevate the body of the subject to that of art, but tattoos as a medium also have the potential to reveal stigmas related to their permanence and subcultures.

In addition to the incredible number of historical documents, and commissioned paper and sculptural works, the ROM has organized a hashtag #ROMINK for virtual public interaction. Featured next to a video of Contemporary Canadian tattoo artists, people are invited to upload images of their own tattoos, producing widespread documentation to be entered into the tattoo cannon.

Text and photo: Alice Pelot

*Exhibition information: April 2 – September 5, 2016, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queens Park, Toronto. Gallery hours: Mon – Thurs & Sat – Sun, 10 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Fri 10 a.m. – 8:30 p.m.