In 1987, Steve Rockwell invented a game. The rules were simple: two players select seven coloured square tiles from 100 available, then take turns laying them onto a 3 x 3 grid until all empty spaces have been filled. Each player’s move is recorded and the ‘winner’ is decided by vote. It is a remarkably simple concept. But don’t let that fool you. Drawing on art historical movements as complex as Cubism, Surrealism and Conceptual Art, the Colour Match Game, as it is formally referred to, has outcomes and references both frivolous and profound. A selection of its aesthetic results, in the form of gridded acrylic-on-canvas paintings, is currently on display at Christopher Cutts Gallery as part of its Starry Night exhibition.

Installation view. Photo: Catherine MacArthur Falls

Installation view. Photo: Catherine MacArthur Falls

The game in its present manifestation has been refined over many years, with small and large elements—including an official game board, printed tiles, and colour names—added over time. At the moment of its invention, Rockwell was working at the Toronto-based Beaver Press and used the leftover colour swatches from the printing process to create the game’s first iteration. Twelve years later, in 1999, the game was played competitively for the first time. Since then, it has seen hundreds of match-ups. Among its players are well-known artists, writers, and other cultural producers, including art historian Linda Nochlin, artist Inka Essenhigh, Drake Hotel owner Jeff Stober, and many others.

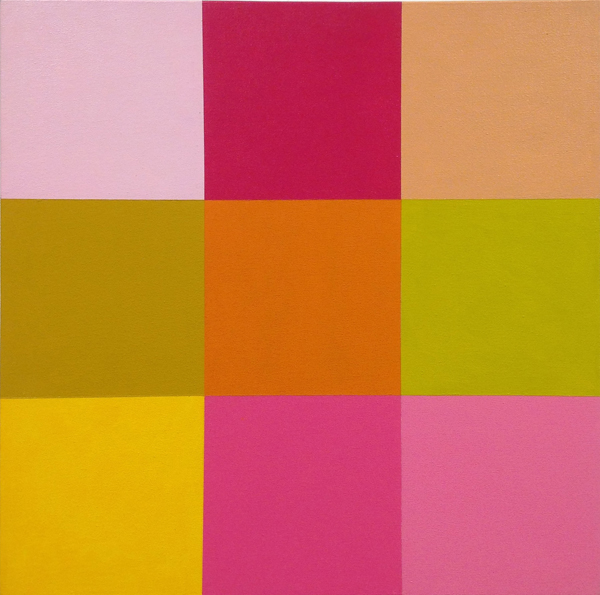

Steve Rockwell, First colour match game, 1987: Beatrice Egolf vs. Steve Rockwell, 2015 acrylic on canvas, 20″ x 20″. Image courtesy of the artist

Steve Rockwell, First colour match game, 1987: Beatrice Egolf vs. Steve Rockwell, 2015 acrylic on canvas, 20″ x 20″. Image courtesy of the artist

At the more frivolous ends of things, the game is simply and delightfully lighthearted, a welcome interjection into an often cliquey and intimidating artworld. At the Colour Match Game opening reception held at Christopher Cutts last September, the continuously occupied game table in the centre of the gallery was a genial shared focus for attendees, who crowded around to watch, comment, and speculate on winners and losers, good and bad moves. The game creates an atmosphere both playful and refreshing, aided by Rockwell himself, an artist as warm and convivial as his game is deceivingly subtle. Of course, adding to this playfulness is the game’s absurdist element. Players ‘compete’ but it is unclear exactly what a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ move is, what makes a ‘winner’ or ‘loser’. How exactly do you beat someone with colour, anyway? Even Rockwell himself admits to not knowing or trying to predict what makes a winner or loser in the final vote.

Steve Rockwell. Photo: Catherine MacArthur Falls

Steve Rockwell. Photo: Catherine MacArthur Falls

Nevertheless, it is in this absurdity that the game quietly nods to its Surrealist predecessors. But it is also here that the game reveals its performative nature. Without the cause-and-effect rationality and measurability inherent to most games, the Colour Match Game relies to a large extent on the fact that its participants and spectators effectively play at playing: they ‘ooh’ and ‘aah’ over well-placed tiles, jeer good-naturedly at bad ones, and collectively generate the sense of competition. In many ways, it is this performativity that makes the Colour Match Game a game at all. It is also what forces us to ask Wittgenstein-like what exactly a game is, what its essential elements are.

Two guests play Colour Match Game, Christopher Cutts Gallery, September 2015. Photo: Catherine MacArthur Falls

Two guests play Colour Match Game, Christopher Cutts Gallery, September 2015. Photo: Catherine MacArthur Falls

The game’s absurdity is not the only way it reaches out to Surrealism, however. As with all games, chance—an element used extensively by Surrealists, like Max Ernst — plays a significant role. Though Rockwell made the rules, the final gridded aesthetic — like those currently on display on the walls at Christopher Cutts Gallery — is the result of numerous factors well beyond his control. Which tiles the players would select, when they place them down and where — none of these can be pre-determined. Following Conceptual Artists like Carl Andre and Lawrence Weiner, Rockwell has created a set of instructions for making a work that is then executed by others. Yet, unlike these artists, whose instructions could be used (or not) to create a prescribed aesthetic outcome, in Rockwell’s game the outcome is far more open-ended, the colour arrangements seemingly endless.

Steve Rockwell, Los Angeles, 1999, Richard Heller vs Steve Rockwell, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 20″ x 20″. Image courtesy of the artist

Steve Rockwell, Los Angeles, 1999, Richard Heller vs Steve Rockwell, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 20″ x 20″. Image courtesy of the artist

Rockwell, however, is quick to point out that this sense of endlessness is actually misleading, that the game does in fact have quite rigid limitations. Through a process of distillation that he accredits to Cubism, Rockwell has limited the overall palette to just 100 colours, the playable tiles to just seven, and the strategic moves to nine in total. Within the confines of the rules, players have surprisingly few choices to make. The game is thus, in effect, a confined universe of possible permutations. As such, it follows perhaps most closely the Conceptual Art of Sol LeWitt, whose open-grid structures and other works create space for complete sets of prescribed permutations to be methodically carried out or at least imagined.

Steve Rockwell, SCOPE Los Angeles, The Standard 2004, Mars Bar vs. Steve Rockwell, 2015 acrylic on canvas, 20″ x 20″. Image courtesy of the artist

Steve Rockwell, SCOPE Los Angeles, The Standard 2004, Mars Bar vs. Steve Rockwell, 2015 acrylic on canvas, 20″ x 20″. Image courtesy of the artist

Where Rockwell’s work differs, however, is in the process by which it achieves these eventual possibilities. Each permutation is arrived at by way of an encounter between two players, what Rockwell calls a “conversation in colour.” With the placement of each coloured tile on the game board, players communicate choices at a very abstract, aesthetic level. Each move involves the non-verbal transmission of a complex message that contains a number of elements: the cultural meanings attached to colour, strategies of collaboration or opposition, aesthetic preferences, and much more. The result is an aesthetic document that records a specific interaction between two people at a specific moment in history—an interaction, moreover, that would be very difficult to capture in words. Like the Cubists before him, Rockwell has thus managed to capture a network of complex meaning within a latticework of simple visual symbols. And through a web of art historical references, has managed to create something novel, enduring, and even fun.

Catherine MacArthur Falls

*Exhibition information: Starry Night, January 16 – February 3, 2016, Christopher Cutts Gallery, 21 Morrow Avenue. Gallery hours: Tue – Sat, 10 am – 6 pm.

A superb synopsis of what Steve Rockwell is actually doing with his Color Match Game and the ensuing paintings. Thank you. Can’t wait to play again.

F. Hill