The current exhibition at Barbara Edwards Contemporary, a selection of William Kentridge’s Universal Archive, succeeds as the gallery provides an intimate encounter with a larger-than-life figure on the contemporary art scene. The exhibition, the third showing of Kentridge’s work at BEC, marks the 6th anniversary of the gallery and it’s 45th exhibition. A show of this caliber is certainly fitting for the occasion. The gallery is known for the impressive roster of artists, Kentridge, Eric Fischl, Betty Goodwin, and Jessica Stockholder among them.

Gallery owner, Barbara Edwards, stands before Kentridge’s Lekkerbreek, 2013. Photo: Catherine MacArthur Falls

Gallery owner, Barbara Edwards, stands before Kentridge’s Lekkerbreek, 2013. Photo: Catherine MacArthur Falls

Perhaps even more than these latter artists, however, Kentridge’s work lends itself to intimacy. Its repetitious evocation of the familiar, of memory flickering through its stores, brings a comforting hominess to the gallery space. The ongoing series, started in 2012, consists of expressionistic linocuts printed on original 1950s dictionary pages. Its subject matter embraces the quotidian: coffee pots, typewriters, cats, trees, the glances and moments that accumulate like bric-a-brac into a life remembered. It is so familiar as to seem almost simplistic; like much of Kentridge’s work, nothing about Universal Archive is obviously or immediately troubling. Yet, its homey familiarity belies darker forces. Rendered in heavy black strokes so fluid they seem brushed onto the page, the prints recall the smudgy charcoal of Kentridge’s celebrated animated films, works like “Felix in Exile” and “History of the Main Complaint”, whose mournful perspicacity earned Kentridge his reputation as one of the most significant cultural observers in and of post-Apartheid South Africa.

Universal Archive (Nine Typewriters), 2013, linocut printed on non-archival pages from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, mounted on paper, 43″ x 57.6″, edition of 20. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

Universal Archive (Nine Typewriters), 2013, linocut printed on non-archival pages from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, mounted on paper, 43″ x 57.6″, edition of 20. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

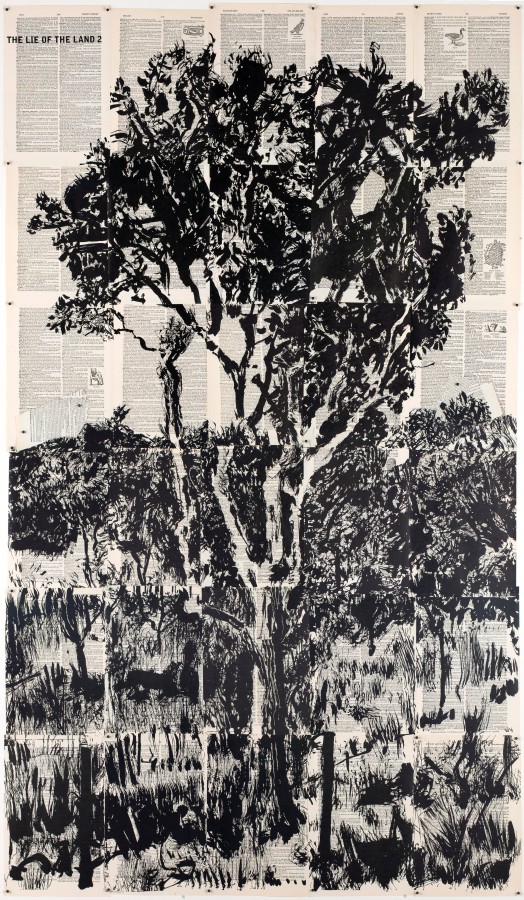

In Universal Archive, Kentridge utilizes these heavy black strokes to achieve, as the project’s title suggests, an archive, a cumulative memory bank of objects and impressions. It is, in one sense, a growing collectivity of irretrievable moments. But the project is also one of distillation and dissolution: individual images border precariously on the edge of abstraction or seem under threat of breaking apart completely. The loose, gestural “brush strokes” of a tree (“Universal Archive, Ref. 45”, 2012, for instance) or the multiple pages on which a single portrait is printed (“Universal Archive, Ref. 35”, 2012) threaten to fly apart under the pressure of pent up energy, the weight of sorrow. Similarly, in a form of narrativity consistent with Kentridge’s work in animation and theatre, a tightly rendered coffee pot or typewriter dissolves in steps over the course of a series, settling into a Cubist-like minimum of identifiable visual signs. Even the heavy nest of thick black lines in “Lekkerbreek”, the most monumental, most solid work in the series, seems somehow tentative, a gathering of marks in danger of vibrating off the underlying dictionary pages. Indeed, in Afrikaans, the word Lekkerbreek, a breed of tree native to Africa, means “breaking easily.”

Lekkerbreek, 2013, linocut printed 30 sheets of on non-archival pages from the Britannica World Language Dictionary, Edition of Funk and Wagnalls, 1954, 67″ x 42.5″, edition of 24. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

Lekkerbreek, 2013, linocut printed 30 sheets of on non-archival pages from the Britannica World Language Dictionary, Edition of Funk and Wagnalls, 1954, 67″ x 42.5″, edition of 24. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

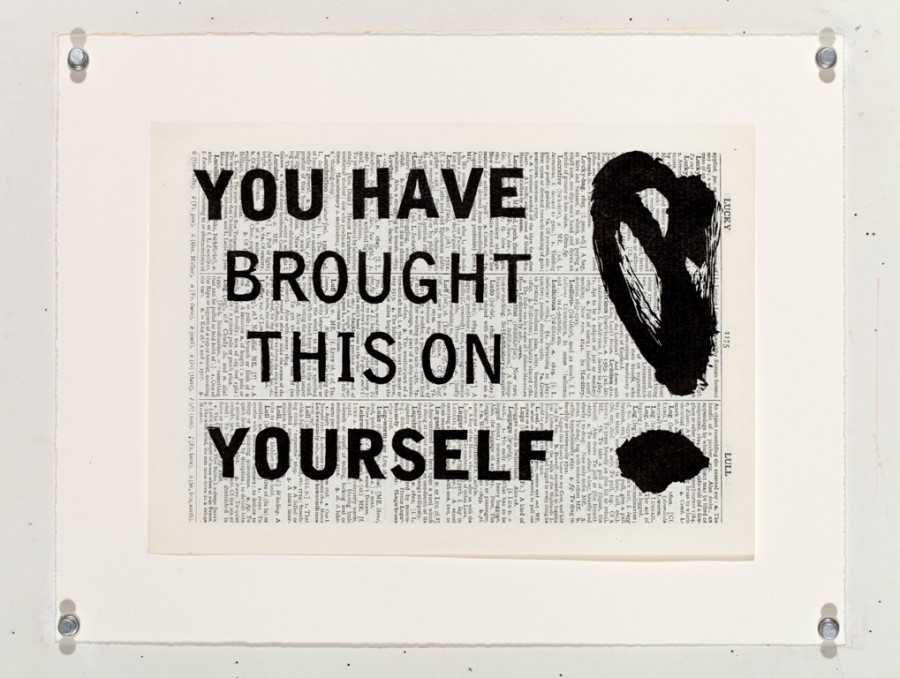

This tension between accumulation and dissolution is characteristic of Kentridge’s larger body of work. His animated films, for instance, utilize a much-described technique of erasure, building up a moving image from a single drawing that is repeatedly dismantled and re-drawn. Likewise, his 2010 revolving sculpture, “Return”, created for Teatro La Fenice opera house in Venice, begins as a chaos of disparate parts that gathers to a two-dimensional image before breaking apart again. Speaking of this latter work, Kentridge notes the “strange utopianism in chaos finding its own order.” By this observation, we may understand Universal Archive as wavering on the border between a Utopian and dystopian view of the world and the objects within in it. As gallery owner, Barbara Edwards, observes, the work speaks to the comforts of home, but also reminds us of the fragility of the objects we love, of our memories, of our very safety. Indeed, it is this ambiguity that has characterized Kentridge’s commentary on his homeland, a society that, like the Lekkerbreek tree, is known for its intense beauty, but also for the difficulties it has endured in order to grow. As Edwards also notes, however, it is not always toward dangerous ends that Kentridge’s images threatens to dissolve: his work morphs in ways that are sometimes threatening, but also sometimes funny. The playful drama of a bristling cat, for instance. The pairing of the ominous scribbled phrase “You have brought this on yourself!” with the dictionary definition for the word ‘lucky’, or the facetious, yet pointed, coupling of a female nude with the word ‘offensive.’

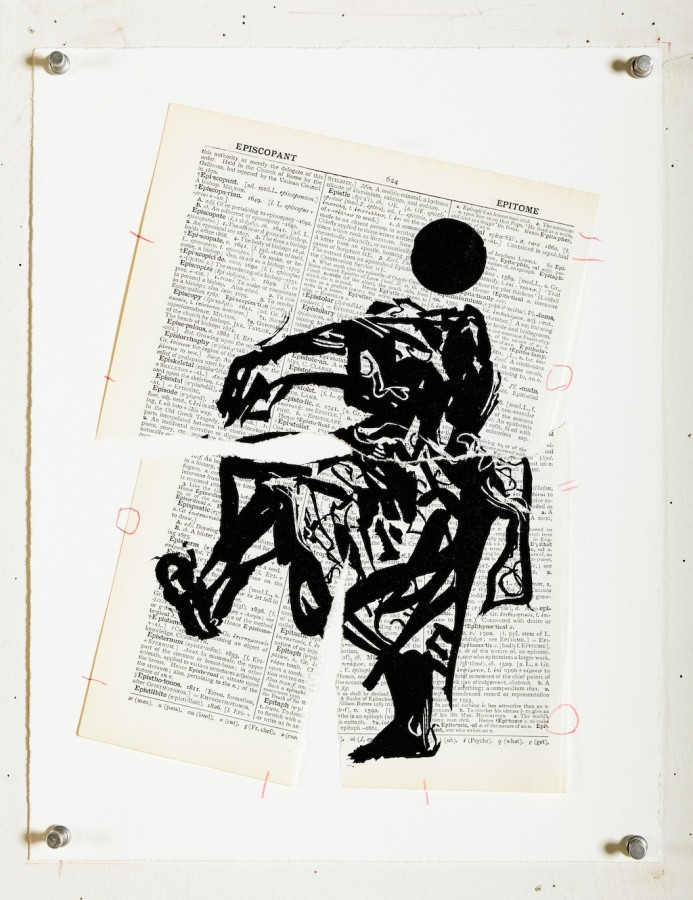

Universal Archive, Ref. 34, 2012, linocut printed on non-archival pages from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 13.7″ x 10.6″, edition of 20. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

Universal Archive, Ref. 34, 2012, linocut printed on non-archival pages from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 13.7″ x 10.6″, edition of 20. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

Universal Archive, Ref. 53, 2012, linocut printed on non-archival pages from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 10.6″ x 13.7″, edition of 20. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

Universal Archive, Ref. 53, 2012, linocut printed on non-archival pages from the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 10.6″ x 13.7″, edition of 20. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

Of course, it is at this meeting of language and image that much of the work’s meaning resides, as Kentridge makes clear the slippages that exist between systems of language and the world. The dictionary’s attempt at order and precision, for instance, contrasts markedly with the sketchiness of Kentridge’s drawings, which seem to take imprecision as their aim. Perhaps more significantly, however, the general project of universality underlying the dictionary, it’s goal of capturing every word, every concept and meaning, stands at odds with the specificity of Kentridge’s visual subjects. Despite the project’s title, it is clear that, at face, his drawings do not add up to anything close to universality. Indeed, the objects he renders—the typewriters, coffee pots, and cats—constitute a continuation of select themes and symbols already present within his oeuvre rather than an attempt on his behalf to capture the world in its entirety. Perhaps, then, Kentridge’s work reminds us of the necessarily incomplete nature of memory, of archives, which are as much about what is forgotten, displaced, even intentionally wiped out, as they are about what remains. This notion is certainly not lost in South Africa, a nation whose own government was charged with destroying archival evidence of its atrocities. Yet, whether Kentridge speaks of the memory of a nation or of an individual, in the end, the power of the project may lie in its partiality, in its bittersweet admonition that nothing can ever be truly captured or remembered as a whole. Perhaps, it is this conspicuous incompleteness of Universal Archive that renders it truly universal, truly intimate.

Installation view. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

Installation view. Courtesy of Barbara Edwards Contemporary

Catherine MacArthur Falls

*Exhibition information: William Kentridge: Universal Archive, September 25 – November 14, 2015, Barbara Edwards Contemporary, 1069 Bathurst Street, Toronto. Gallery hours: Tuesday to Saturday, 11am – 6pm (or by appointment).