Installation view. Photo: Miklos Legrady

Installation view. Photo: Miklos Legrady

Stepping into Gallery 1313 you have a ‘wow’ feeling. Both the theme and the medium of these works are unusual. It takes some time to recognize that you are looking at metal pieces and a unique technology. Electrostatic paint on aluminum is a technique that has been used in the industrial world for colour finishing and protecting architectural siding for a while, but it is rare in art world. In our age of short attention spans and endless hunger for new things, artists try to find new forms of expression that will surprise the viewer. As Jackson Pollock stated, “My opinion is that we need new techniques. And the modern artists have found new ways and new means of making their statements. It seems to me that the modern painter cannot express his age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any past culture. Each age finds its own technique…” (New York, 1950). It seems that Canadian artists are leading this search for new mediums: Steve Driscoll uses industrial urethane for his landscapes and David Altmejd recreates the magic of decay as a beginning of new life in his large Plexiglas display cases.

Darcia Labrosse at the opening reception. Photo: Phil Anderson

Darcia Labrosse at the opening reception. Photo: Phil Anderson

For Labrosse, as the title of the show, Metal language III, suggests, the medium is very important. She chose her medium for its endless possibilities in producing fine art and for its vibrant pigment and robustness. I almost get dizzy watching the short video of the artist making these pieces. The term “electrostatic painting” describes a process by which the properties of electricity are used to apply a high-solids coating to any conductive material. Using the “opposites attract” principle, the painting equipment is charged with one electrical polarity while the metal objects to be painted are charged with the reverse polarity. The coating is attracted to the metal surface and electronically bonds to that substrate.

Darcia Labrosse’s video showing the procedure of electrostatic painting. Photo: Phil Anderson

Darcia Labrosse’s video showing the procedure of electrostatic painting. Photo: Phil Anderson

The procedure is toxic, so it happens in an industrial setting, and Labrosse wears a protective suite like an astronaut. She works at an amazing speed with different spray guns and a large brush. The procedure is very intuitive—she doesn’t use sketches. Colours cannot be mixed to make other colours, but can be added, one on top of another, to produce varying hues. Matte and glossy varnishes can also be used for visual effect. A final firing in an oversized, high-temperature oven cures the pigments to the metal surface, very much like an enamel finish. The final work can be displayed on a stand as sculpture or hang on walls in a gallery. Despite being metal, the work is very ethereal.

Installation view. Photo: Phil Anderson

Installation view. Photo: Phil Anderson

In her artist statement, Labrosse writes, “Overcoming the gravity of representation, automatism and acquired reflexes, I mix brute force and translucid emotions to paint an ontological, disquieting, enigmatic human figure free from artifice, universal in its expression.” Labrosse mentions her fascination with the “distorted human body” like the five-thousand-year-old Iceman, the victims of the Holocaust, the mercury poisoned residents in Minamata and the mummies of the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, among others. It’s easy to connect this to the Baroque theme of Vanitas or Memento Mori, the warning that all will die. The people in the Capuchin Catacombs gave serious thought to death, deciding how they should be displayed—their clothing, their posture. The rich ones wanted to be put in glass coffins. They left detailed instructions in their wills. Those catacombs look like a museum of death. Most of the residents’ faces show their death struggle, making a rather scary display. However, a few of them, mostly children, are beautiful—in a terrifying but fascinating way.

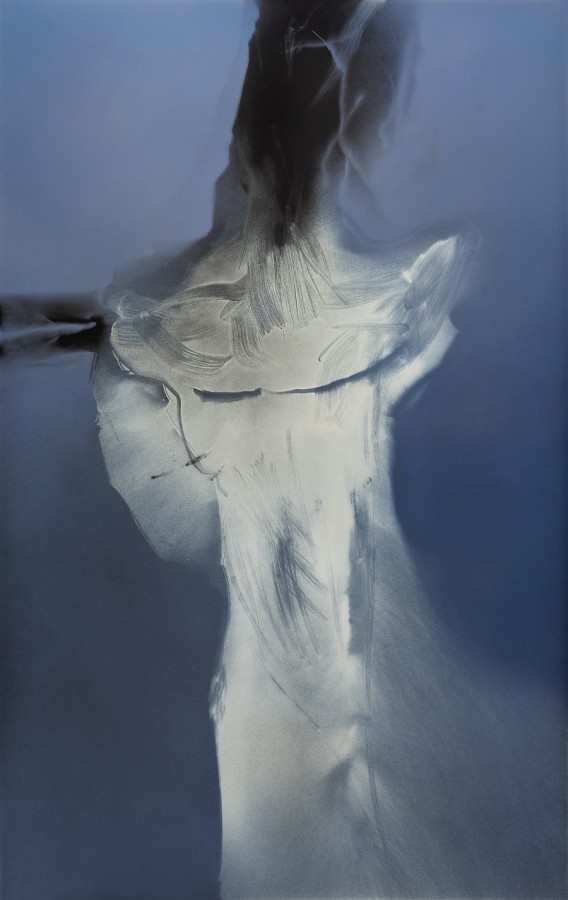

Darcia Labrosse, Industrial No.16, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, 60 x 38 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Darcia Labrosse, Industrial No.16, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, 60 x 38 inches. Courtesy of the artist

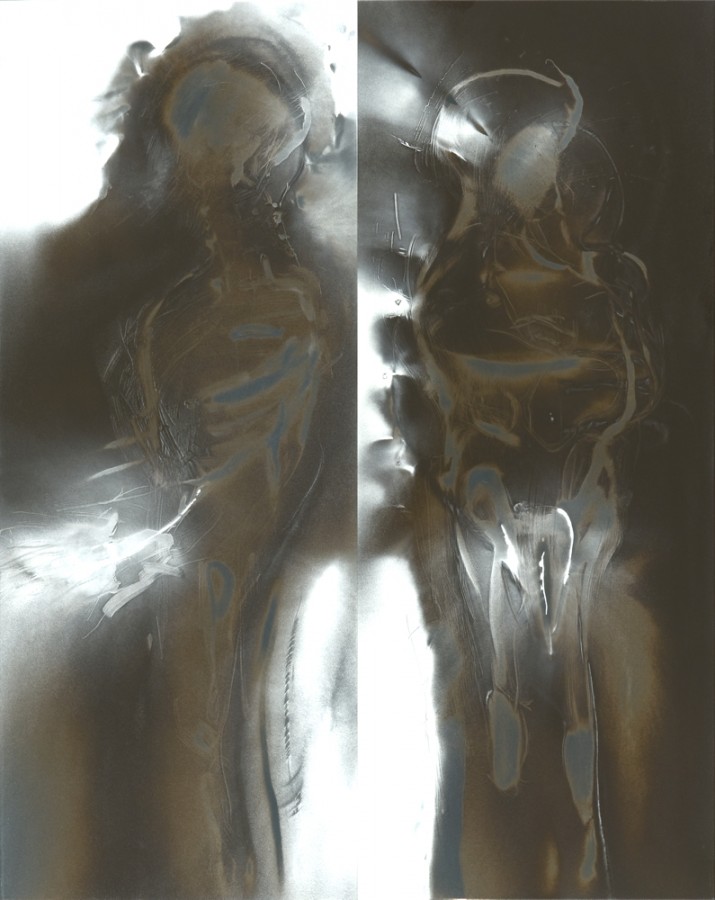

There is nothing scary or terrifying in Labrosse’s work. Light is a major element in her composition and it must be the celestial light people who have experienced clinical death tell of, that shines from Labrosse’s ghostly figures, or rather shines through them (“Industrial No.16”). Their suffering, if there was any, doesn’t show. Most of them, like “Industrial Brass No.10”, actually don’t seem to be fully dead – they appear in the midst of a transformation – they still have flesh, but have no eyes, so they can’t see anymore. Their bones are visible but claws are also creeping out of them. “Industrial No.12” also shows the process of decomposition. The front of a female’s cadaver is open so we can see the internal organs—the large intestines like crawling worms, the spinal cord curving on the left side, and the genitals still recognizable. A yellow light radiates through the throat and genitals – like those chakras are still alive. Yellow seems to represent the life energy that used to inhabit the bodies when they were still alive. Red surrounds the figures like a comforting blanket for their fearful journey (Industrial Coffer No.15), or splashes inside and around them like the blood they lost in their struggle against death (Industrial No.19).

Darcia Labrosse, Industrial Brass No.10, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, 48 x 25 inches & Industrial No.12, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, gold-plated screws, 48 x 25 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Darcia Labrosse, Industrial Brass No.10, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, 48 x 25 inches & Industrial No.12, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, gold-plated screws, 48 x 25 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Darcia Labrosse, Industrial Copper No.15, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, 60 x 38 inches & Industrial No.19, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, 60 x 38 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Darcia Labrosse, Industrial Copper No.15, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, 60 x 38 inches & Industrial No.19, 2013, Powdercoated aluminum, 60 x 38 inches. Courtesy of the artist

About her style, Labrosse says, “With its figurative undertones, my work is an oscillation between two worlds with the abstract constantly feeding the tension figure/ground. In the last decade, the Metal Language corpus I have labelled Existential Expressionism, is wilfully branching out from the Abstract Expressionist tradition, primarily because of [as Robert Atkins pinpointed in ART Speaks] ‘its fierce attachment to psychic self-expression…less a style than an attitude.’”

Darcia Labrosse, Untitled Diptych No.48, 2012, Powder coated raw aluminum, 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Darcia Labrosse, Untitled Diptych No.48, 2012, Powder coated raw aluminum, 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Labrosse’s bodies are not skeletons, they are occupying both the physical and eternal world. Still, it is obvious that these bodies belong to a different world, the world of darkness. They have passed into the deepness of the Abyss. This after-world, however, doesn’t scare us. They are beautiful corpses. Death here becomes a ritual, The Final Ritual, as Pierre Lévy called it his article in 2011. They are in constant movement, performing a strange kind of Dance of the Dead. They can’t be identified. Their faces are no longer recognizable but they still radiate the luminous light of their spirits and their auras still surround them. Their bodies still remember suffering and happiness. These are special “portraits” where the conscience and the unconscience, the real and the transcendental world, merge, making human existence come full circle. The images are mystical. They are powerful and, instead of showing the deepness of death, they stand to prove the deepness of human existence. These bodies are here in the real world with us and at the same time looking down at us from their spiritual height – and Labrosse helps us witness their transformation. Shadows of the after-world filled with light. What is left from their physical life is still shining along with eternal light. They are mesmerizing. You can’t help but love them.

Emese Krunák-Hajagos

*Exhibition information: Darcia Labrosse: Metal language III, September 16 – 27, 2015, Gallery 1313, 1313 Queen Street West, Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed – Sun, 1 – 6 p.m.