Is abstract painting still relevant today? After reaching its apex locally in the 1950s, abstraction has since largely elided Canadian art historical discussion. But while such tendencies as conceptual, installation, and new media art emerged onto the scene, production of abstract painting has persisted through these intervening decades. How is today’s abstract art different from its predecessors? This question is taken up by the current group exhibition at Angell Gallery, titled Superabstraction, which takes a look at instances of abstraction in the practices of several contemporary Canadian and international artists. The exhibition was spurred by gallery owner Jamie Angell’s visit to a recent MOMA exhibition on the advent of abstraction in the early twentieth century, when the irreverent European avant-gardes first purged figuration from their canvases. Consequently, Angell was inspired to explore the rippling effects of this seismic artistic innovation on non-figurative painting today, almost 100 years later.

Bradley Harms, Mini Scrambler, 2013, acrylic on canvas , 18″ × 24″. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Bradley Harms, Mini Scrambler, 2013, acrylic on canvas , 18″ × 24″. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

While the exhibited artists employ the familiar visual vernacular of abstraction, they aren’t exactly reiterating their modernist forbearers. For one, this generation of artists have parsed the intervening art historical developments between late modernist abstraction and now, from Pop to Minimalism to Conceptualism. Toronto artist Daniel Hutchinson’s alluring black paintings, for example, redeploy the monochrome through Minimalism’s preoccupation with embodied perception. Displayed in a darkened room, each work is lit by a colour gel-treated fluorescent light tube. Glowing jewel tones of blues, greens, and purples seductively graze the painted surface, revealing the stiated grooves of each brushstroke of viscous black paint. The use of florescent light begs for a mention of Dan Flavin, who is most significantly remembered for introducing light fixtures into the artistic toolbox in the 1960s. Flavin thought of his florescent works as “image-objects,” referring to the relay of the viewer’s attention between the artwork as material object and as visual phenomenon. Hutchinson’s monochromes similarly educe a perpetual back-and-forth between the materiality of the painted work and the fleeting optical phenomena conjured by the eerie, fluorescent glow.

Daniel Hutchinson, Painting for Electric Light (Analogous Colour), 2013, oil on canvas with fluorescent light, 77″ × 96″. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Daniel Hutchinson, Painting for Electric Light (Analogous Colour), 2013, oil on canvas with fluorescent light, 77″ × 96″. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

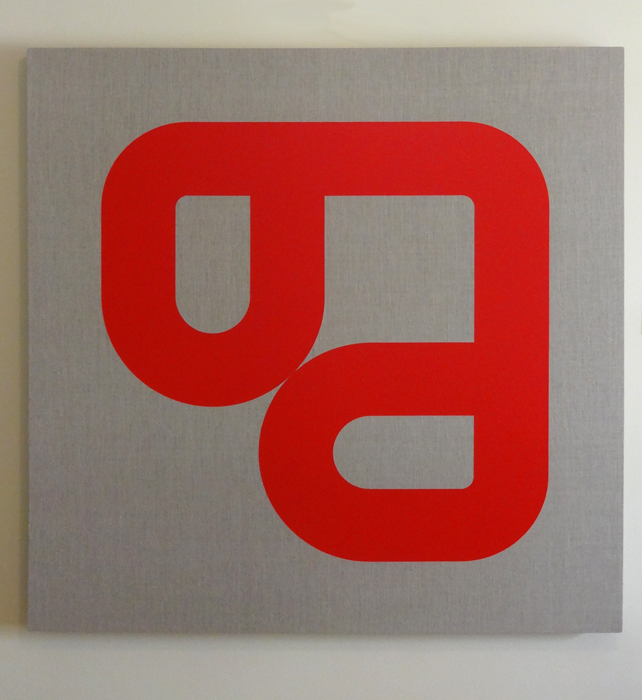

Torontonian Neil Harrison’s oil on canvas works are informed by a diametrically different sensibility. Each work features a monochrome, logo-like design, painted with the precision and flatness of hard-edge abstraction. Harrison’s imagery makes references to the visual vocabulary of hieroglyphs, diagrams and, of course, corporate logos. The titles of the two works, Black Square and Red Square (both 2013), retrieved from my memory bank Kasimir Malevich’s paintings after the same titles executed a century ago. Declaring his floating shapes to be “pure feeling,” Malevich had exhibited his black square in the corner room, effectively superseding the traditional Russian icon with this mythical modern icon. Are Harrison’s assertive symbols, with their sharp aesthetic of commercial branding, the updated icons of our late capitalist era?

Neil Harrison, Red Sqaure 2, 2013, acrylic on linen , 46″ × 46″. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Neil Harrison, Red Sqaure 2, 2013, acrylic on linen , 46″ × 46″. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

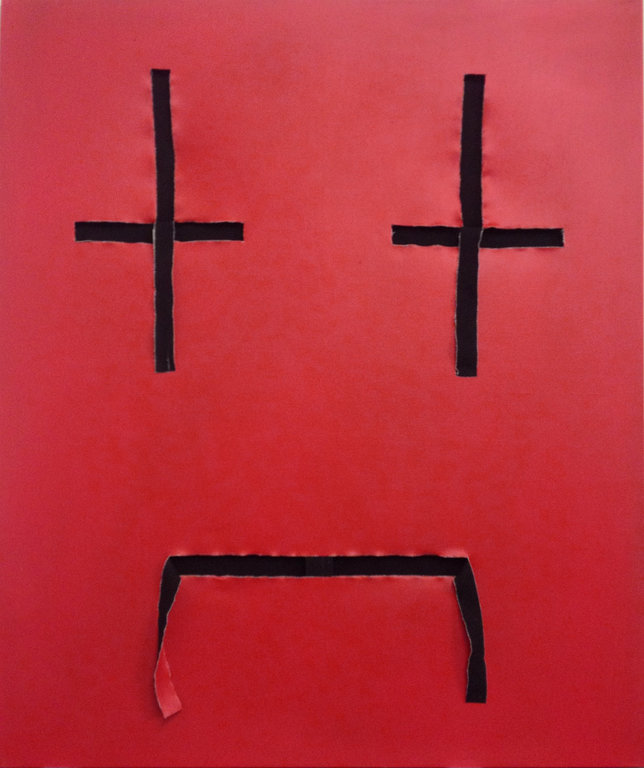

The cut canvases of Derek Mainella, who is based in London, UK, summon the spectre of yet another major modernist figure. In the 1950s, Lucio Fontana attacked the sacrosanct surface of his canvases, slicing them open in a gesture of iconoclastic energy and machismo. Mainella also breaches the integrity of the canvas surface, but with formalist control and playful Pop sensibility. In Unit (R5) from 2013, parallel excisions in the upper half of the white canvas create strips of cloth that hang lankily down the lower half. The negative space of the perforated surface and the subtle tonal changes of the twisting ribbons of hanging canvas are cleverly employed to create a pleasing linear composition. Another work, Untitled (Acid), is more playful and ironic in tone, with the strategically sliced canvas producing the image of an emoticon-like angry face.

Derek Mainella, Untitled (Acid), 2013, oil on canvas, 48″ × 40″. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Derek Mainella, Untitled (Acid), 2013, oil on canvas, 48″ × 40″. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

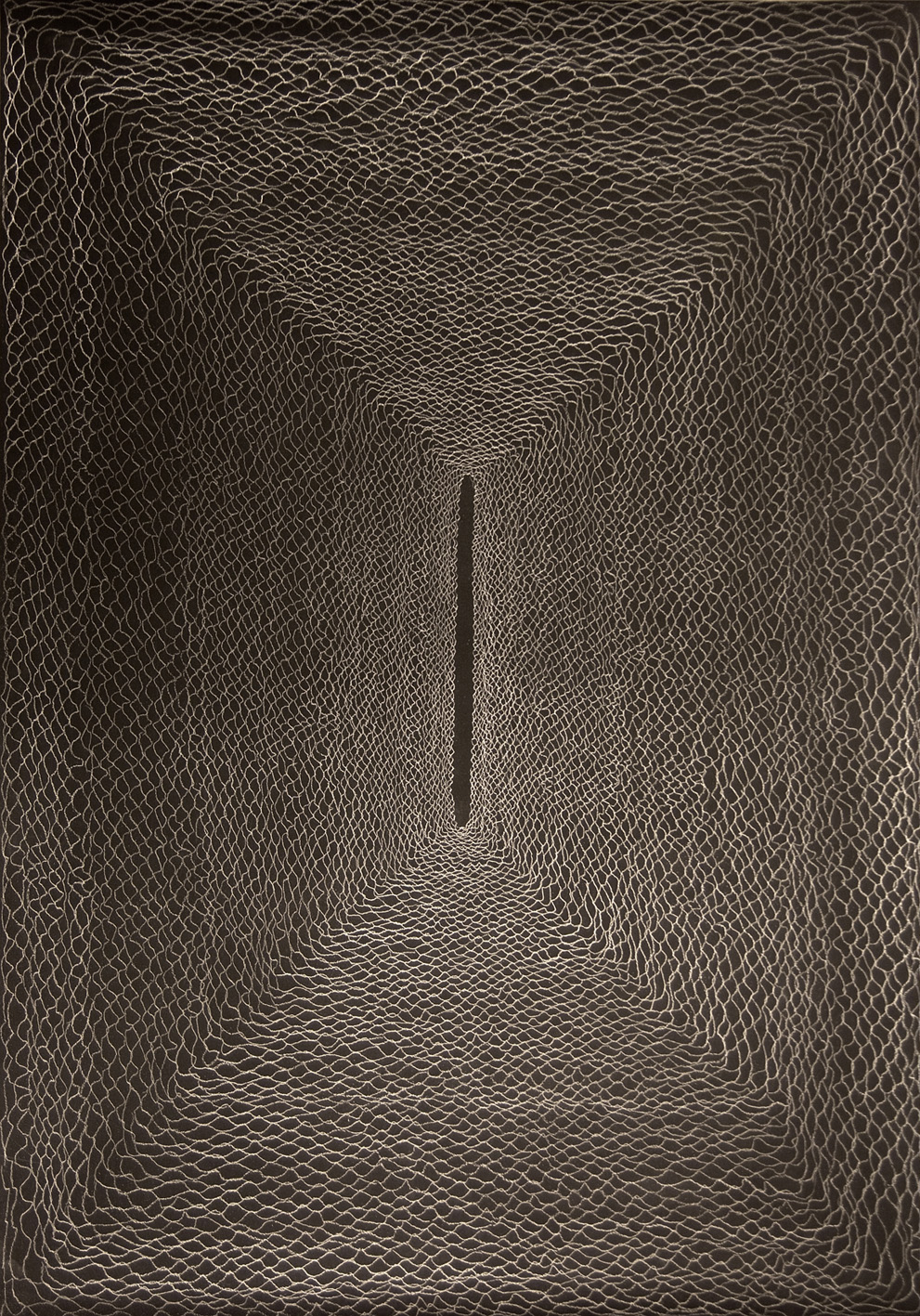

In contrast to the assertiveness of Harrison and Mainella’s abstraction, the two works by Toronto-based Vessna Perunovich hang like demure wallflowers. But upon a closer look, these abstract pieces become magnetic. In each, graphite lines scribbled on black paper form concentric echoes from the circumference of the canvas toward the centre, leaving at last a small orifice into a black abyss. This method of working from outside-in, letting the frame echo into and “compose” the internal image, recalls Frank Stella’s black stripe paintings. But whereas Stella had famously declared of his work, “what you see is what you see,” Perunovich’s abstraction is more encouraging of associative excursions. The silvery, weaving pencil lines are evocative, for example, of a net or fence, tying this work thematically to the concern with boundaries that pervades her multi-media artistic practice.

Vessna Perunovich, Sliver of Hope (diptych), 2013, acrylic and graphite pencil on paper, 30 x 22 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

Vessna Perunovich, Sliver of Hope (diptych), 2013, acrylic and graphite pencil on paper, 30 x 22 inches. Courtesy of Angell Gallery

From Piet Mondrian’s rhetoric of purity to Malevich’s claim of arriving at the “zero of form,” modernist abstraction since its early days has largely aimed at the distillation of painting. The reductive imperative was again echoed by the mid-century critical heavyweight Clement Greenberg, who declared that painting had to strip itself down to the unique essence of the discipline – namely, flatness. The contemporary iterations of abstraction presented in this show, however, derail and undermine this modernist teleology toward a pure, timelessness painting. Today’s abstraction is expansive rather than reductive, incorporating external allusions into the pictorial image. These contemporary artists seem insistent on acknowledging their post-ness in the art historical timeline. Their varied practices thus find coherence in this exhibition by dint of their self-reflexivity on the viability, place and meaning of abstraction today.

Amy Luo

*SUPERABSTRACTION / Derek Mainella, Daniel Hutchinson, Bradley Harms, Kineko Ivic, Neil Harrison, Kenneth Emig and Vessna Perunovich. Exhibition dates: October 4 – November 16, 2013, Angell Gallery, 12 Ossington Avenue, Toronto. Gallery hours: Wed to Sat 12 – 5 p.m.

Thank you for this literary exhibit.

From Angela Angell Mrs. Perry Angell